JOSH SIREFMAN, M.U.P. ’03, is a native New Yorker who began his urban planning career in Detroit after completing his M.U.P. coursework in 1996. But now his work in another great North American city is making cross-border headlines. As the head of development at New York-based Sidewalk Labs, a subsidiary of Alphabet, Sirefman is overseeing the design of a futuristic neighborhood near downtown Toronto that proposes adaptable modular buildings, passive house construction, and a goal of being climate positive (a step better than climate neutral). In addition, connected technology could enable services ranging from a shared fleet of autonomous vehicles to notification when coveted Adirondack chairs in waterfront parks are available for a sit. While Sidewalk Labs touts the site as “a place that’s enhanced by digital technology and data, without giving up the privacy and security that everyone deserves,” some aren’t convinced. The project has sparked a lively public discourse about how it will toe the line between the two successfully.

Prior to helping found Sidewalk in 2015, Sirefman was senior vice president of U.S. development at Brookfield Properties and then managed his own firm, where his projects included Cornell University’s applied sciences campus in New York City and the revitalization of the University of Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood. He began his planning career at the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, and when he decided to return home to New York, he walked into the New York City Economic Development Corporation and asked if they had any openings. While he now looks back on that cold- call as “bonkers,” it worked — he had a job offer a week later, and further down the road, he even served as the organization’s interim president. In early 2002, Sirefman joined Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, during which time he served as chief of staff for the deputy mayor for economic development. “It’s easy to forget what it was like in those months right after 9/11,” Sirefman says. “It was a tremendously trying time, but also an extraordinary opportunity to think big about the city’s future.” Sirefman was the city’s lead on the redevelopment of the World Trade Center and spearheaded projects that spanned the city and its boroughs. “We drove big, complicated initiatives across agencies in tandem with communities,” he says. “With the World Trade Center site, there were incredibly difficult politics. Every aspect was complex, but at the same time, every- one involved had this personal and professional mandate of doing what needed to be done — and the balance of urgency and patience — to keep it moving forward.”

In advance of Taubman College’s Shaping Future Cities symposium in November — in which Sirefman will participate — he talked with Robert Goodspeed, assistant professor of urban and regional planning, about Sidewalk Toronto, the urbanist-technologist divide, and the future of cities.

Robert Goodspeed: The Sidewalk Toronto project has generated a lot of excitement but also critical commentary, especially around issues like data privacy and the use and ownership of data. How are you addressing this issue, especially given the project’s stated goal of creating a place with a spirit of ongoing innovation?

Josh Sirefman: Cities have always collected and analyzed data about what is going on within them, whether it is health inspections or 311. New technology is giving cities ways to collect more data more cheaply and easily, but right now the technology is racing ahead of the best practices for privacy. Cities everywhere are struggling with this. One of the opportunities we are most excited about is the chance to work with government partners in Toronto, expert advisory panels, and the public to define a set of rules that can serve as a model for how to benefit from new technology while respecting individual privacy. I think we will end up with policies and processes on privacy and data security that will exceed Canadian law and ultimately will be world-leading. We have a lot of ground to cover still, but we are deep in, working with many parties on how to develop the right approach.

We approach everything relative to data with the intent of creating an open platform that allows many parties to have access to data, so that it can be a part of whatever innovation they can layer on.

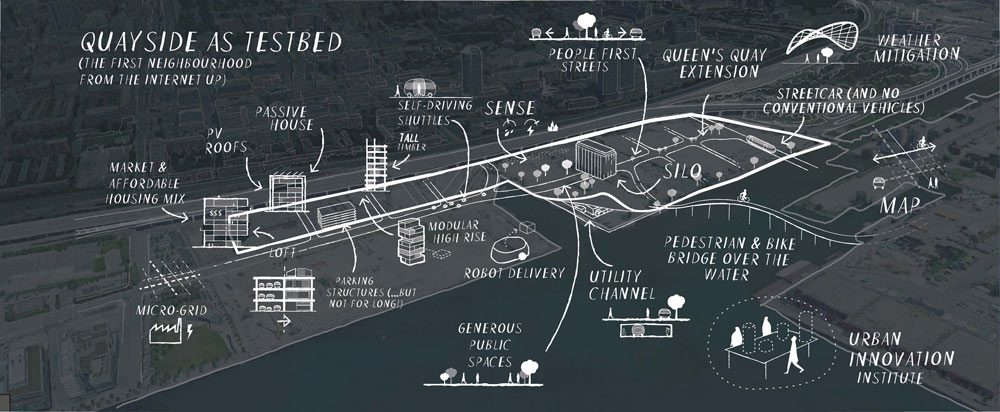

Sidewalk Toronto is billed as “combining people-centered urban design with cutting-edge technology to achieve new standards of sustainability, affordability, mobility, and economic opportunity.”

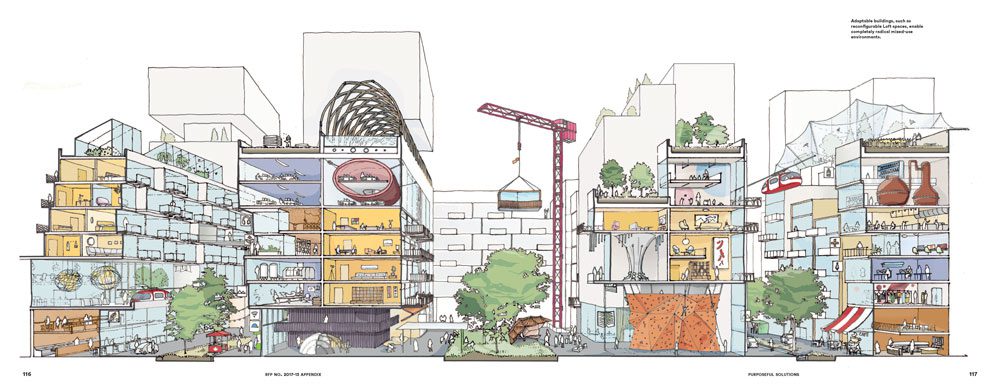

But the question about ongoing innovation covers much more ground than just data — it’s building materials like tall timber, it’s taking advantage of self-driving cars to give street space back to people. Our aspiration is to create a set of conditions that can enable ongoing innovation. This is not about technology for technology’s sake, or about saying here is the technology, therefore let’s do this — “smart cities” is a term I don’t often use because it has connotations that are counter to what we’re trying to accomplish. This is about understanding what existing technological tools might enable, and then creating the conditions that can adapt as additional capabilities emerge. One of the critical keys to that is the policy and regulatory approach: How do you create a framework for how things can be thought about differently, and how can that first step of innovation be taken and then adapted based on learning and in real time? That’s the essence of what we’re trying to do.

Goodspeed: How to address those issues for future cities at large is something a lot of places will be interested to learn from your experience. You’ve done a wide variety of engagement activities in Toronto. What are some of the resulting inputs or creative ideas that are emerging or being refined that you think will shape the project?

Sirefman: As you can imagine, there are lots of opinions, ideas, and questions. Overall, we have been thrilled with the level of engagement we’ve seen. There are some clear themes: People want to make sure this place is open to everyone, they support our goals of sustainability and affordability, and they really want to make sure we are thoughtful about data, security, and privacy.

The single biggest learning for me has been how, in the abstract, people fill the void with what they think this is all about — versus when we can really engage and talk about the idea with the kind of thinking we’re trying to catalyze. It changes the dynamic enormously.

“I’ve always thought that the planning field has an opportunity in front of it to be more of a leader in pushing the envelope in how we can best manage urban growth … combining planning and equitable economic development as an emerging way to think about things a little bit differently.” — Josh Sirefman

The second takeaway is that there is a whole series of ideas that are starting to emerge. We’ve taken an initial approach of the work focusing on different subject areas, whether that’s the built environment, public realm, mobility, or sustainability, and then we’ll start integrating them and taking a holistic approach to seeing what all these things add up to. That part of the dialogue is just beginning, and it’s been fantastic.

We now have a public facility with prototypes of things we’re working on. Thousands of people have been able to visit and see things like, for example, a different kind of paving that would allow a dynamic control and flexible use of the streets and eliminate the static boundaries of how streets can be managed, enabled by the underlying capability that autonomous mobility provides. And we’re very much intrigued by timber as a building material and its potential to create not just sustainability impacts, but meaningful approaches to lowering the cost to build. People have been incredibly engaged on issues — both very broad and very focused.

Goodspeed: Rethinking infrastructure is an example where new thinking is going to challenge the traditional division between the public and the private sectors, and their responsibilities and roles. How do you see relations between the public and private sector evolving with more and more cities exploring new technology applications?

Sirefman: We believe in government; a lot of Sidewalk Labs’ leadership has served in government. Government is not going to go away, and it shouldn’t. But new technology gives us the opportunity to think about things in a way that embraces that and recognizes the interrelationship between the multiple layers of cities — infrastructure, the public realm and built environment, the community. The roles and responsibilities between public and private actors is one example where I think you can really start to think about different approaches, whether to challenges such as financing much-needed infrastructure systems or solving affordable housing. As technology gives us more tools to work with, government will have to figure out how to provide flexible regulatory approaches to allow experimentation, and private actors will need to understand how to ensure broader public policy implications are addressed.

Sidewalk Toronto, a futuristic neighborhood east of downtown, will include modular buildings and passive construction, with a goal of being climate positive.

What we’re trying to do in Toronto — by working hand in hand with government partners, in particular a tri-partite agency called Waterfront Toronto — is bring a level of thinking that is not traditional for a private entity about issues that cut across all. That’s because we have the ability to build a team to think about these issues differently and try to understand the capabilities that technology allows. How we all follow up with the right kind of public-private model, given this opportunity, will hopefully grow out of our collaboration with government.

Goodspeed: That actually relates to my next question. There’s a big cultural difference between innovative technology companies and the urban planning field. What are some lessons that you think planners could learn from big technology or entrepreneurs, and vice versa? As someone who has crossed back and forth, what should that interface look like?

Sirefman: We talk a ton about the urbanist-technologist divide — I’ve had a four-year crash course in that, and I think Sidewalk Labs is very much on the forefront of bridging it. It has really opened my eyes to think differently — about possibilities, about questioning assumptions — while also respecting the process, engagement, and checks and balances that are required to try new things in the urban context. Somewhere in the middle is this balance that allows you to think about how to integrate the digital and the physical. I think this is going to be the basis of a profound shift in the way we all think about urban innovation and the way we think about planning education and the field in general.

With planning education, the set of tools to work with are profoundly different now, and it’s very hard for people to understand that. We need to think about how to harness those tools and, accordingly, how to change the rules in order to allow things to happen in different ways. That’s a huge opportunity for programs as they look forward.

Goodspeed: Can you describe in more detail the different tools available to professionals now versus when you were a student?

Sirefman: One specific example is how we think about city shaping through the control of land use and tools like zoning and building code. I believe there’s the potential to move past those kinds of fixed-rule controls into a performance-based approach where the outcomes that matter, however one wants to define them, are what can govern and be monitored and adjusted, versus a pre-determined prescription of what activities can or can’t happen in a place or how a building needs to be built. Going all the way back to your original question about how to enable ongoing innovation, we have an idea called outcome-based code, whereby the amount of information that can be processed in real time, with complex analytics, can provide the tools to enable dynamic decisions about the built environment.

As another example, U-M is deep in autonomous mobility. Beyond the tremendous mobility implications, there also are massive opportunities in how we can think about the design of streets and the assumptions we make about how they’re used, as well as the relationship between streets, public space, and buildings. We’re all just starting to scratch the surface on the potential implications from this set of tools, but the impact will be considerable. All the more reason for us to be focused now on how to harness this capability in ways that will be additive for life in cities.

Goodspeed: That’s partly my motivation for convening Shaping Future Cities and pulling in innovative practitioners and scholars. It’s a question that our master students will be eager to consider — the alignment between their curriculum and the state of the art. How do you see the professional field of urban planning changing during the course of your career? What are the types of things you’re thinking about now that wouldn’t have been on anyone’s radar coming out the urban planning master’s program when you graduated?

Sirefman: Cities are more important than ever, and what makes great cities and great places has only become more important. I’ve always thought that the planning field has an opportunity to be more of a leader in pushing the envelope in how we can best manage urban growth, if you will, combining planning and equitable economic development as an emerging way to think about things a little bit differently. The planning field needs to be out ahead of the opportunities presented by technology. I’ve grown obsessed with this notion of boundaries that are starting to change in every aspect. How do we think about governance models that allow flexibility and adaptability? Do we understand how people want to live and work and what that means for cities? In some ways, planning seems like it still has to catch up to that.