The way we move around touches every single part of our life, says Corinne Kisner, M.U.P. ’13, the executive director of NACTO

By Katie Vloet

WHEN CORINNE KISNER VISITS a new city, she’ll probably notice the landmarks and attractions. She definitely will notice how people are getting from place to place if there’s any public life in the street, and whether there is an inviting outdoor space for people to sit and eat a sandwich or play with a child.

“I notice things intellectually that a lot of people will notice viscerally, like how much greenery has been incorporated into the city,” says Kisner, M.U.P. ’13. “I’ll notice nerdier things, too, like crossing distances and curb radii.”

As executive director of the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), Kisner is one of the foremost voices in the country speaking out about the importance of building safe, sustainable, accessible, and equitable cities. And that means being well-versed about everything from, well, curb radii to the ways that automated vehicles could change city life to the importance of creating bicycle infrastructure that is accessible to people of all ages, abilities, and backgrounds.

NACTO has grown rapidly in recent years, from about two dozen member cities and transit agencies when she began as a fellow in 2013 to 81 now. Notably, Kisner’s career path has followed a rapid trajectory during that timeframe as well, culminating with her appointment as executive director early in 2019. “It’s been a period of a lot of growth. We were a three-person team when I started at NACTO,” Kisner says. “I was able to build on a lot of strong early work, and we now have 31 employees.”

In her time at NACTO, she has helped to shape the narrative about transportation in cities. The organization promotes the idea that transportation infrastructure should serve the public good and that the public sector should advocate for the needs of all users in designing streets and transit.

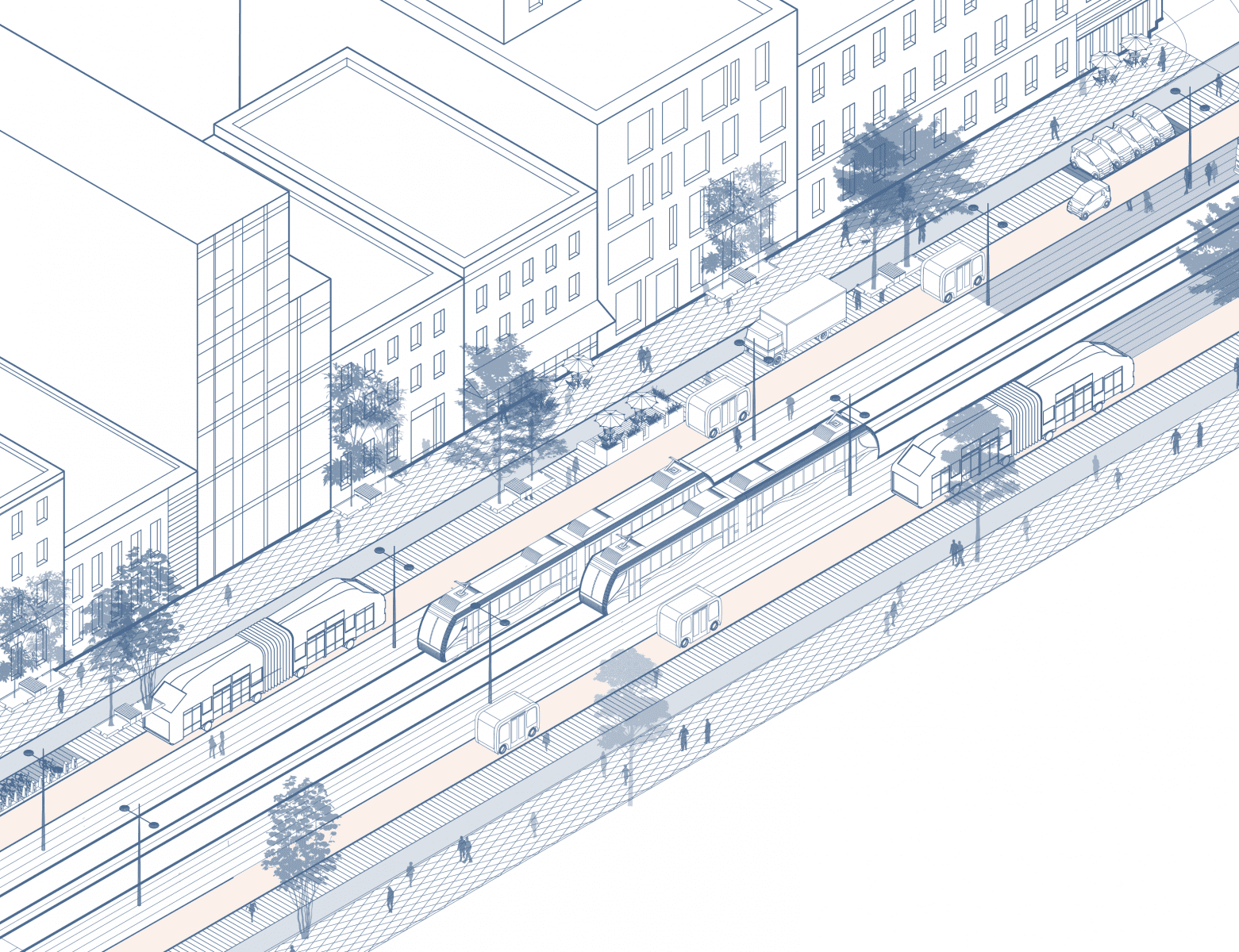

“The way we move around touches every single part of our life. Streets in particular, and transportation systems more broadly, have a major impact on our lives, yet they’re often designed such that the people using them are an afterthought,” Kisner points out. “We have many places where streets are designed just to move vehicles. There’s a huge opportunity for city streets to be a vibrant experience, but not if we’re designing them exclusively for cars.”

Kisner is leading NACTO during a particularly interesting era in city transit. Micromobility — the use of shared bicycles and electric scooters, for instance — is a visible trend in cities large and small. On-demand connectivity and autonomous vehicles are changing the landscape as well. Kisner says she is seeing “a lot of energy” related to the trend of moving people efficiently to and through cities, something that is particularly important due to the increasing effects of climate change.

Recent NACTO projects include “Blueprint for Autonomous Urbanism,” which was developed with a steering committee from member cities and transit agencies and details the concrete steps needed to ensure equitable, people-first cities.

“We’re at a really interesting inflection point with the policy right now,” she says. With the growing prevalence of ride-hail services and the emergence of automated vehicle technology, “there is a potential to repeat a lot of the car-focused mistakes we made in cities in the 1950s.

But there’s also an outcome where we think about what’s the city we want to see and work backward to implement policy to achieve that vision.”

A key focus of Kisner’s policy work is ensuring that city leaders consider social justice when they design transportation systems. “There is a lot of systemic racism built into the way our transportation systems have been designed. It perpetuates in a lot of damaging ways. Poor transportation systems have meant limited access to jobs and opportunities for communities of color. Literal highways built through communities is a clear example of that.”

She points to a bike-share program in Philadelphia as an example of a conscious improvement in this area. Stark divisions along class and race lines tend to be a feature of bike-share programs, so people who run the program in Philadelphia has made an effort to speak with low-income and minority residents and provide bike share stations where the residents say they would be most useful.

“My ideal city is one where I can walk or bike comfortably to lots of places. One with dense, vibrant street life. One where I can have an enjoyable commute that doesn’t have too many stressors, such as, Is a car likely to hit me when I cross the street? Is the air pollution harming my lungs? Are public transportation and bicycling among the options that people can choose?.”

— Corinne Kisner, M.U.P. ’13

They also have provided access plans and cash-payment options for low-income residents. As a result, 45 percent of pass holders are from nonwhite groups and 35 percent have incomes less than $25,000 a year.

Kisner’s views about equity in city transportation are, in many ways, rooted in a class she took at Taubman College: Social Justice and the City, taught by Kimberley Kinder, associate professor of urban and regional planning. “That class informed how I think about equity,” says Kisner. “Transportation is a means to something else, yes, but it also intersects with all of these parts of urban life.”