Chris Johnson, B.S. ’09, M.U.P. ’15, keeps airports safely humming along at Passero Associates

By Amy Spooner

AS AN ARCHITECTURAL design intern at Jacobsen Daniels Associates in Ypsilanti, Michigan, Chris Johnson, B.S. ’09, M.U.P. ’15, walked by the airport planner’s office one day and inquired about a maze of circles on an airspace plan on the wall. Johnson’s colleague explained that the circles denoted airspace restrictions around an airport. “It was a happy accident that the airport planning bug bit me,” Johnson says. “I never looked back.”

Chris Johnson, B.S. ’09, M.U.P. ’15

Today, Johnson’s work centers on those circles, along with other considerations that help airports remain safe and run efficiently. Johnson, now an airport planner in the St. Augustine, Florida, office of Passero Associates, says he is a longtime fan of airports. Like most travelers, though, he did not give much thought to their layout and operation. “I’ve always thought airports are magical. Somehow, everything works.” Now, he understands the careful thought and planning that goes into making that magic, like the safety clearances around runways; the location of parking garages and rental car facilities; and the flow of travelers through security, the terminal, and on to their destinations. “All of these things are strategically thought out to make sure the system works cohesively because one error or issue in the system can throw off everything else,” says Johnson.

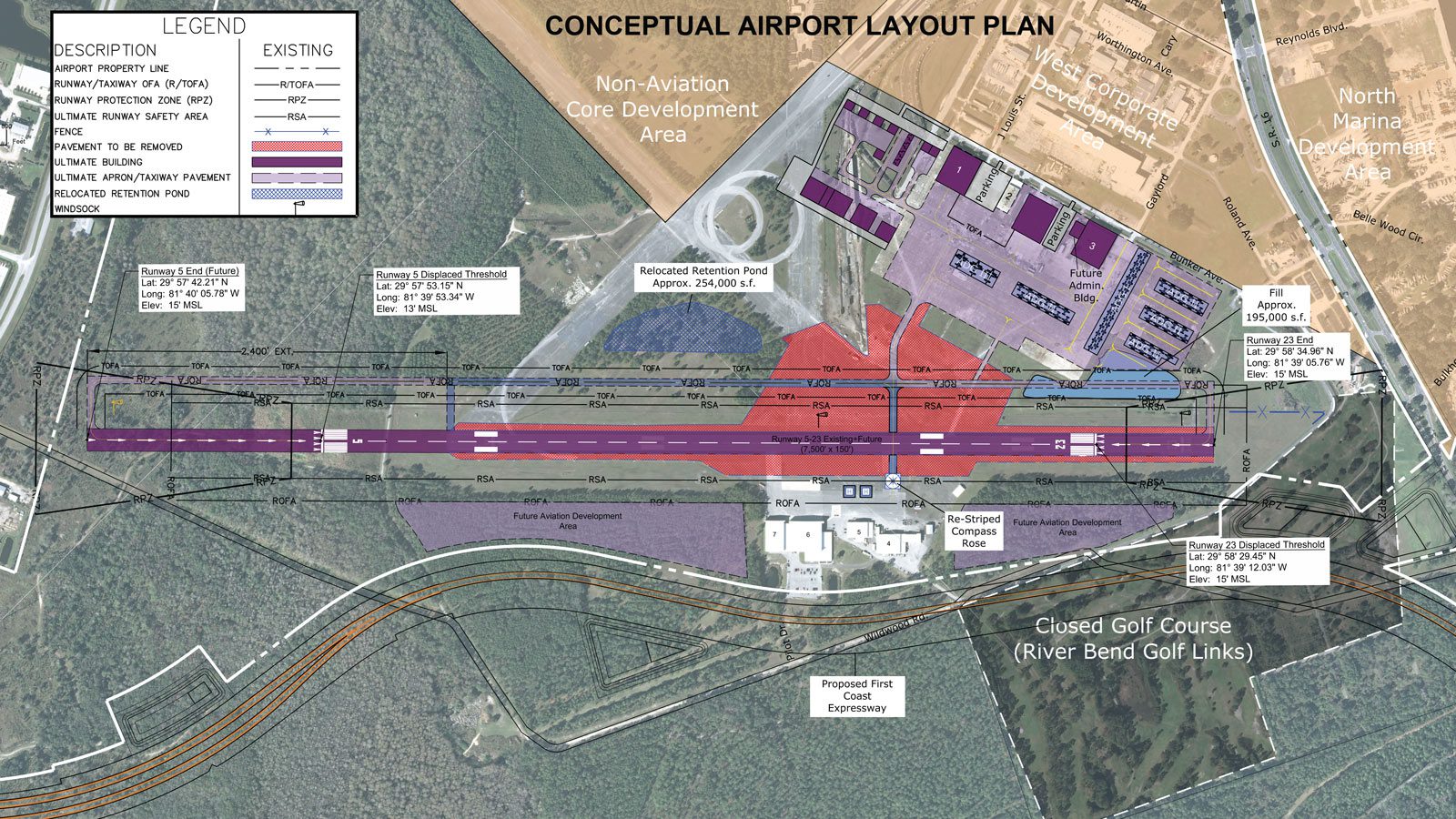

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations protect airspaces around airports — those circles that first hooked Johnson — and determine the length of runways and taxiways. These regulations also help determine the placement of airfield facilities in airports. Johnson’s initial work incorporated these regulations to determine the location of potential aircraft hangars, parking aprons (also referred to as tarmacs), and taxiways/taxilanes. In 2010, Johnson was promoted to an airport planner position and began to specialize in airspace analysis.

In 2013, Johnson saw the need to return to Taubman College to learn the skills that a masters in urban and regional planning could provide. “The broad education showed me how the different aspects of my work fit together,” says Johnson, who worked as an aviation planner for the Georgia Department of Transportation after he earned his M.U.R.P. degree. “Because of my education, I know how to incorporate elements from a comprehensive plan into my airport work, and there’s nothing on a comprehensive plan that stumps me.”

Comprehensive planning is more important to airports than ever. The International Air Transport Association forecasts a 3.5 percent growth in passenger enplanements, and in the past 20 years, passenger enplanements have surged from approximately 1.4 billion in 1998 to nearly 4 billion in 2017. Most of Johnson’s work involves revamping existing airports to meet increased demand. “What worked for an airport five to 10 years ago may no longer work today,” he says. “We forecast airport growth so that we can think about the number of new hangars we’ll have to build, by how many feet we’ll have to extend runways to accommodate larger aircraft, stresses on aging infrastructure, and other considerations.”

“All of these things are strategically thought out to make sure the system works cohesively because one error or issue in the system can throw off everything else.”

— Chris Johnson, B.S. ’09, M.U.P. ’15

In developing and revamping airport master plans, Johnson leans heavily on his training in land use planning and law. Poles, trees, and other obstructions near runways can cause safety hazards. Therefore, airport owners want to own as much nearby land as possible in order to mitigate those obstructions. If land acquisition is not possible, airport owners can pursue avigation easements. With the rise of multimodal transportation, airport planning initiatives should be incorporated with rail and highway planning initiatives to create an efficient transportation system. This is especially important during airport expansion, which can lead to increased aviation activity and, potentially, increased roadway congestion. “We often work on airport master plans as part of municipal master plans, thinking about rights to the land around the airport, as well as alternative ways to get to the airport during peak traffic times,” Johnson says.

While congestion on the surrounding roads can be a headache, congestion at airports can have catastrophic results. Disaster can obviously strike if two planes collide on a runway. However, a pilot’s incorrect perception that a collision is possible may result in an aborted takeoff, severely impacting passengers and airport operations. Johnson says one of the proudest moments of his career came when he stood in the air traffic control tower at Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport, looking out at an end-around taxiway (EAT) visual screen. Pilots use EAT visual screens to minimize aborted takeoffs because the screens help them differentiate between aircraft taxiing around the departure end of a runway and those entering the departure end of the runway. The Detroit project had been Johnson’s first time determining the size, height, and location of a visual screen on an airfield. “The controller said the EAT visual screen was fantastic, and I was thrilled. Sometimes as planners, our work is very future-focused. So to see something come to fruition and know that I’m doing my part to protect people energizes me.”