Dominique Price, B.S. ’98, M.Arch ’00, harnesses the influences of Bo Bardi, Bruder, and Gang to create social infrastructure in the City by the Bay

By Amy Spooner

WHEN DOMINIQUE PRICE FIRST STUMBLED upon architecture, as an undergraduate enrolled in a different program, she was drawn to its abstract nature — different from the there’s-only-one-answer approach of other disciplines.

It’s one of the things she still loves about the work today.

“Clients come to us when they’re looking at difficult problems for which the answers aren’t already known,” Price says. “A lot of our work centers on developing emerging typologies and bringing architecture to projects and situations that may otherwise be outside of the discipline.”

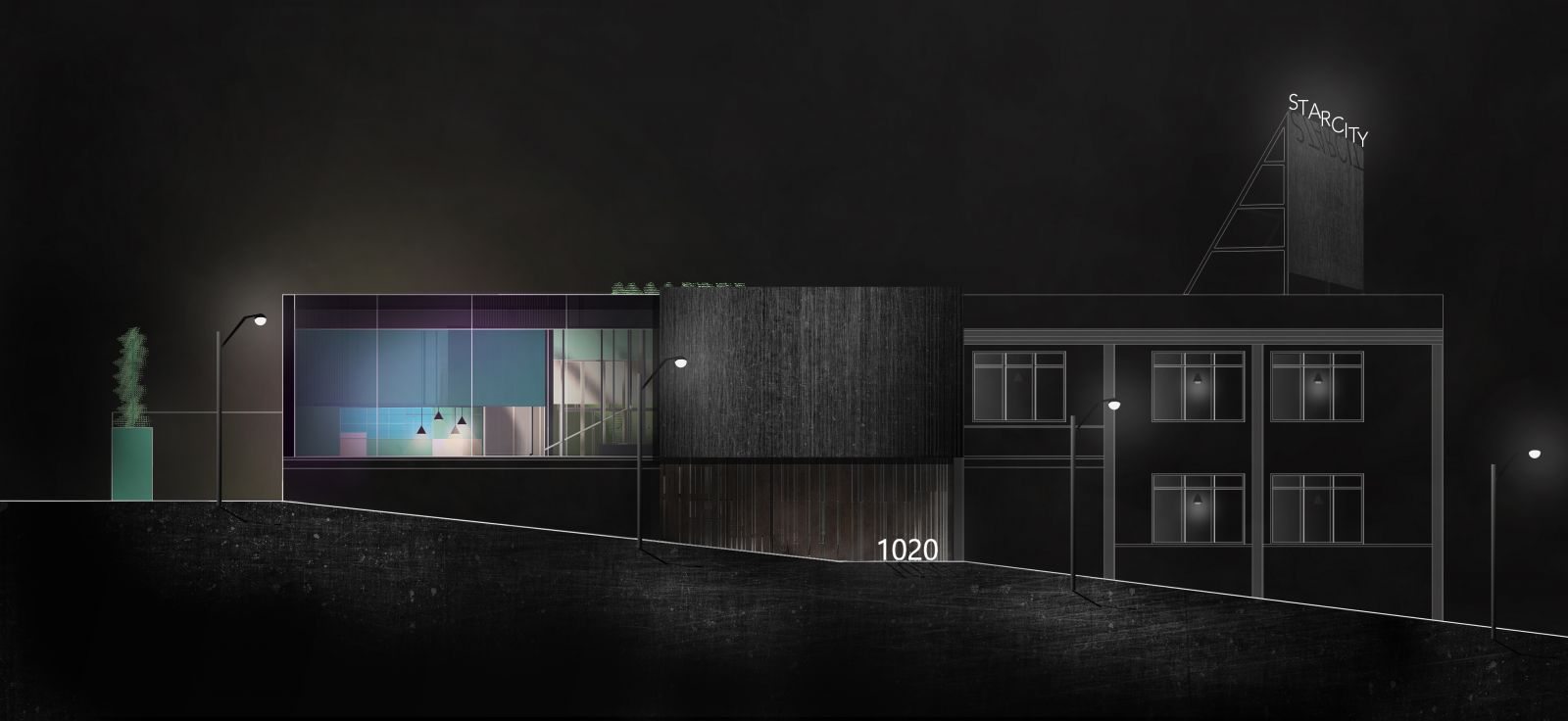

Price, B.S. ’98, M.Arch ’00, is the founding principal of AS-IS, a female-owned San Francisco-based architecture and interiors firm. As the city faces income and housing disparities, she is inspired by the challenge of making it a sustainable place for a diverse society to live in. “Diversity is one of the things that makes San Francisco so special,” she says. “We are at risk of losing that if we don’t find new solutions for making the city work.”

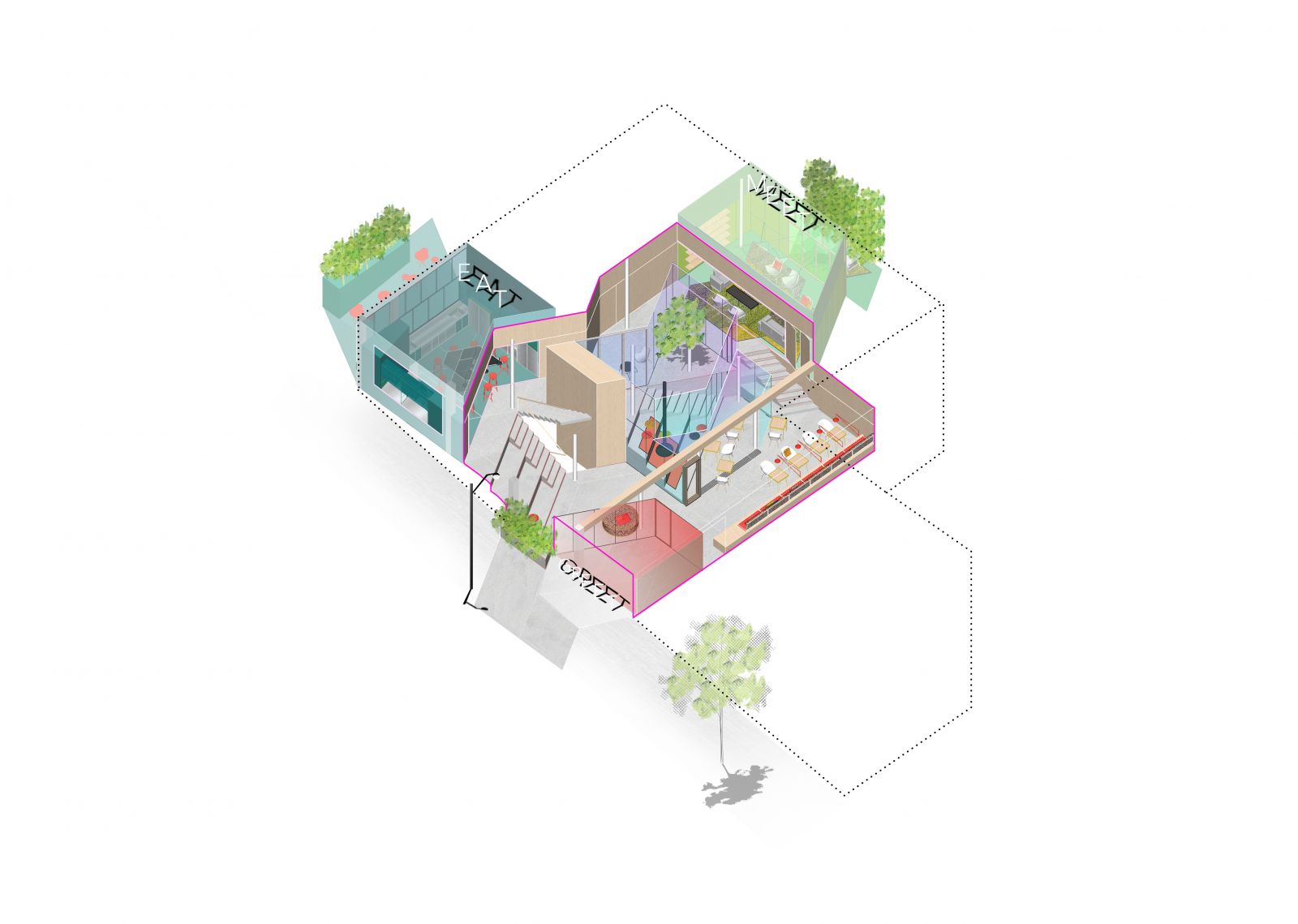

Price describes AS-IS as a spatial intervention practice and says she and her team focus on the developing objectives of architecture that emerge from a context as-is, not just the object/form. Their web address as-is.us alludes to their establishment as an integral architecture studio, interior studio, and urban studio. “We practice simultaneously as an architecture and an interior studio, always looking intently at the larger cultural and urban impact of the work. It requires everyone on our team to be able to think on every level of architecture.”

The goal? “Creating social infrastructure,” she says.

That passion for social infrastructure draws from her study of Lina Bo Bardi, an Italian-born Brazilian modernist architect who is known for emphasizing the social and cultural potential of architecture and design. As an early-career architect with Will Bruder in Phoenix, Price fell in love with Bo Bardi’s work and won a Booth Traveling Fellowship from Taubman College in order to follow her footsteps in South America. Her affinity for the architect also teed up the next step in Price’s career: when the fellowship ended, she went to work for another admirer of Bo Bardi’s work, Jeanne Gang, at Studio Gang Architects in Chicago. “Lina Bo Bardi created social infrastructure by mapping her design and her architecture in the people and the place and those same values are present in Jeanne’s approach, as well,” says Price.

When Price felt the tug back to the West, San Francisco was a natural landing spot. The Great Recession was a challenging period for making a move, but it was also a time when society was hungry for new ideas. At Will Bruder Architects and Studio Gang, Price had worked on a lot of community projects like museums and libraries, but the economic downturn meant funding for many projects of that ilk was lacking. She saw that workplaces often filled the social infrastructure void. “Particularly in San Francisco, where so many people are coming from other places and are without family, offices became the center of their social networks. The genre of the workplace became very appealing as territory for a new form of public space.”

Price’s work on Co-living projects in San Francisco balances familiarity and the unexpected so that “places act as a ladder.”

Price’s work on Co-living projects in San Francisco balances familiarity and the unexpected so that “places act as a ladder.”

During this period, Price worked as a design director with Gensler and with MMoser Associates, two companies focused on workplace design, and she led the design on projects ranging from the emerging typology of coworking to mega-scaled corporation headquarters at locations across the globe. Throughout this time, however, she simultaneously began building a part-time practice focused on community-oriented projects in the spirit of Bo Bardi. “It allowed me to work on projects that required more intimacy than I could provide in a corporate setting,” she says. It also narrowed the leap she would make when she went out on her own. “Instead of ripping off a Band-Aid and diving in blindly, I slowly built my practice to a point where I had plenty of projects, a base of largescale experience, and a clear agenda for our work.”

AS-IS, now a team of 10, focuses on what Price calls cultural projects that span genres. They include an urban cultural center, co-living projects, and a residence that is “not a house” but a kind of summer retreat that allows for spontaneous co-habitation intended to strengthen human connections. She also continues to be intrigued by the idea of public-private spaces: That notion of workplaces acting as agents of community-building that captured her imagination when she first moved to the Bay Area has expanded into retail, education, and housing.

At Gensler, her projects included Airbnb’s headquarters. When she and her team did a site analysis of the newly emerging area of the city where it would be built, they realized the city didn’t plan space for the public to coalesce. So the centerpiece of the Airbnb design became a massive atrium designed as an interior plaza. “It fits Airbnb’s business model of embedding travelers into neighborhoods. And it helps them to be a great neighbor,” she says. Price sees more mutually beneficial public-private opportunities happening in the future, co-existing with traditional public gathering places like plazas. “I think they can support and provide more diversity in the options that are available to people in cities,” she says of the public-private model. “At my firm, we create urban interiors — moments where you let the city in.”

She is excited about several projects in the pipeline, as well as the process of making them a reality. “We’re using the design process and its deliverables to fuel our souls as creatives in addition to developing the design; we try to weave that approach into everything we do.” And harking back to that open-ended way of problem-solving that drew her to architecture in the first place, Price says it’s very much a team effort. “I’m not going to drop a sketch in the hands of others and tell them to make it happen. Our product is the result of our merging of talents and interests, and that’s what keeps it fresh.”

The University of Michigan was where that idea first hit home for Price, who says the institution is a ladder that allows people to build on who they are and emerge into a different place — a concept mirrored in her co-living and social infrastructure projects. “My work thinks about how architecture can, from one perspective, have a familiarity that allows it to be accessible, yet introduces the unexpected so as to advance what we already know. These are the practices that allow us to share in one another’s culture, and in architecture, the places that act as a ladder. That’s what Michigan was for me.”

She also says Michigan’s team-based educational model produces the kind of colleagues that make her collaborative approach more effective. “Michigan teaches students to be able to jump onto a team, navigate the waters together, and support each other. Some new architects enter the workforce just wanting to be told what to do or, on the other end of the spectrum, are devastated that they’re not sole authors. Michigan teaches you to succeed as a team and to adjust when myriad forces come at you and change the scope of the problem.” Clients want to shift direction, building codes evolve, budgets shrink, and short project schedules are a new norm, Price notes: “You need to know how to stay tenacious, buoyant, and be resilient while keeping the objectives of the work at the forefront. Schools that train their graduates to navigate the complex climate of building culture will better enable them to build architecture that contributes to both society and the discipline.”