As a nonagenarian, Rudy Horowitz, B.Arch. ’58, remains thrilled to be an architect — of his grandchildren’s birthday cakes.

Before designing monster truck, swimming pool, and grand piano-shaped confections, he designed houses (including his own), airport lounges, healthcare facilities for clients ranging from NYU Hospital to Rikers Island prison, and much more.

He also created and trademarked an early computer-aided design program for architects, based on AutoCAD, which he called Geocad and sold to firms nationwide.

But before all that, he was the architect of his freedom.

Horowitz was born in Poland in 1929. When he was an energetic, art-loving 10-year-old, Germany invaded his country. The rise of Nazi-fueled antisemitism began before the tanks rolled across the border, but it quickly grew worse after the occupation. In his memoir, Avoiding the Cracks (Amazon, 2018), Horowitz chronicles how the Holocaust came to his town — how normal life for his upper-middle-class family became a fight for survival.

“I’m not by nature a risk-taker,” Horowitz says. “But earlier in my life, it was a necessity.”

As Horowitz details in his book, his parents’ courage and connections, as well as a healthy dose of good luck, enabled him and his immediate family to survive the Holocaust. The Polish city of Oswiecim, where the death camp Auschwitz was built, is just 25 miles from the Horowitz’s hometown of Sosnowiec. Most of the city’s 30,000 Jews were sent to the camp. But while Horowitz and his family were forced into Sosnowiec’s Jewish ghetto, they were spared in multiple deportation roundups. Then his father, an ophthalmologist who was evacuated with the Polish army to Romania, secured false Chilean citizenship papers that enabled Horowitz, his mother, and his older brother, Oskar, to leave Poland and wait out the war in internment camps for enemy aliens in Germany and France.

After the family reunited in Palestine, following a six-year separation from Horowitz’s father, they applied for immigration to the United States but were told that the waitlist for the Polish quota was five years long. With conflict brewing around the establishment of Israel, Horowitz’s parents sent him and Oskar to live with a relative in Munich until the family’s quota number came up. But because of a snafu with their visas, the brothers ended up back in Poland, which by 1948 was under communist control behind the Iron Curtain. For the second time in their young lives, they risked death as they escaped the country — this time by finding employment as harbor freighter captains’ representatives and stowing away in the hold of a coal-laden freighter bound for Sweden. They finally arrived in New York in late 1949, and Horowitz found work on a factory assembly line and as a sign painter.

Almost immediately after occupying Poland, the Nazis prohibited Jewish children from attending school. Yet, despite all the shortages and frequent hunger, Horowitz’s mother used some of the family’s resources to engage a tutor to continue her sons’ education; she also found someone to teach them English. With that foundation, Horowitz found ways to continue his education throughout his decade of upheaval, so when he heard that New York’s Cooper Union School of Art offered free courses in art and architecture, he had the skills and credentials to apply. He enrolled in the night program in order to continue working during the day and studied under architect-cum-sculptor Tony Smith, who had worked for Frank Lloyd Wright and was a friend of Jackson Pollock. As part of his studies, Horowitz built a model for the three-pavilion luxury home that Smith designed in Guilford, Connecticut.

Horowitz was drafted into the army during the Korean War, where he served for two years as his battalion’s draftsman. After his discharge, he returned to Cooper Union and spent two more years in the night school studying architecture. Since in those days Cooper Union did not offer an accredited degree course, he transferred to the University of Michigan at the dean’s recommendation.

At U-M, Horowitz, took 20 credits per semester and held a part-time job. “I was obsessed with getting my degree and finally getting my adult life and my career started,” Horowitz says of his time in Ann Arbor. “I was about five years older than most of my classmates, and my philosophy was tempus fugit.”

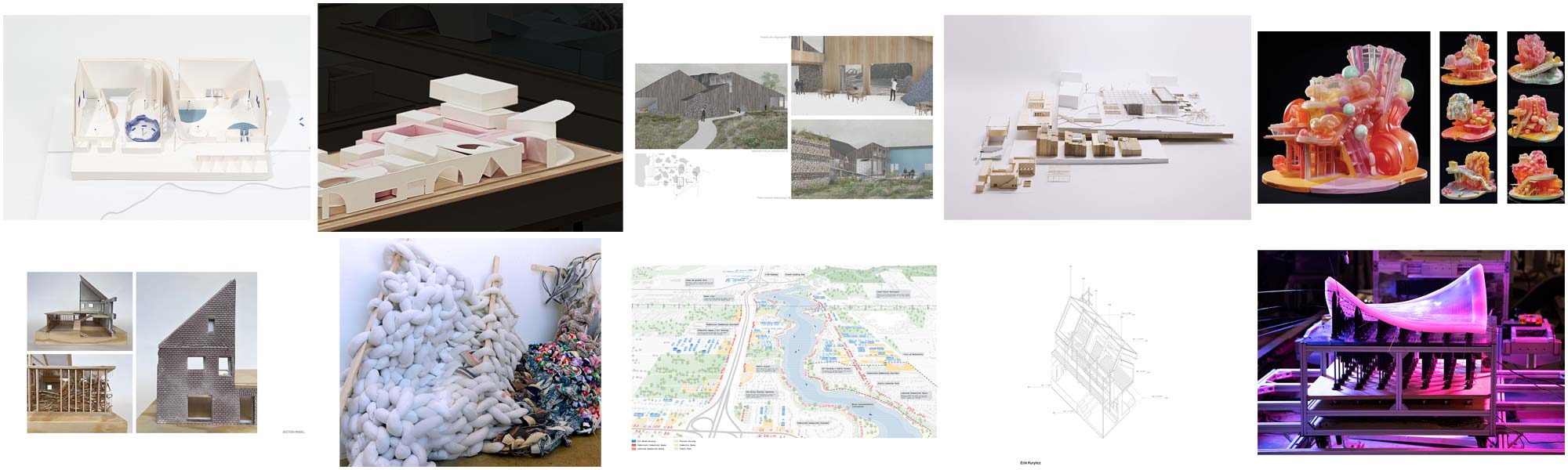

Horowitz didn’t have time for the social activities that most college students embrace. Yet, he says his fellow students shaped his academic experience as much as his professors did. In particular, he recalls Leslie Tincknell, B.Arch ’58, and class president Bob Ziegelman, B.Arch ’58, who combined their thesis design project — a civic center — with his own, creating a four-foot-by-eight-foot model. He remains friends with them both.

“While in New York, I was associating with people whose backgrounds were very similar to mine. Michigan helped me assimilate into day-to-day life and society. I became more American at Michigan than I ever did before or after,” Horwitz says.

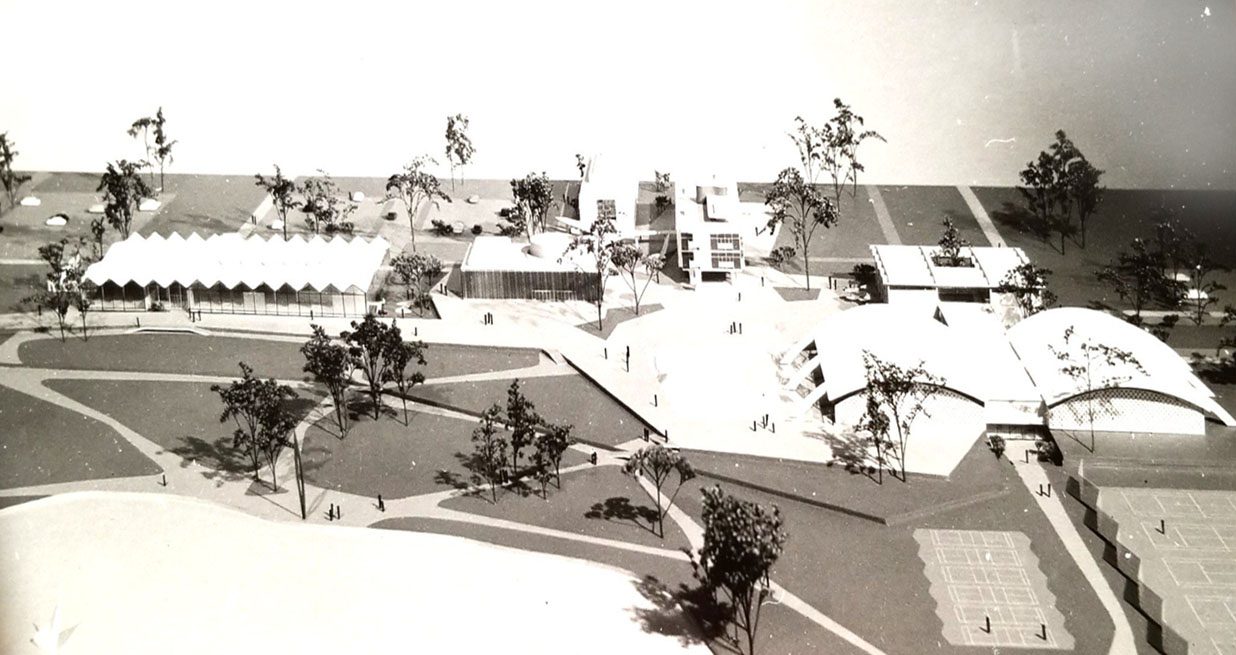

Thesis project completed by Horowitz, Leslie Tincknell, B.Arch ’58, and Bob Ziegelman, B.Arch ’58.

After graduating, Horowitz won a Booth Traveling Fellowship from U-M, taking him back to Europe for the first time since his harrowing escape. He studied how European architects were using concrete as an architectural building and finish material, rather than a structural element. Over five months, he traveled nearly 10,000 miles in an MG sports car and “had a ball” seeing his native continent through an architect’s lens. His many visits with architects included a meeting in Rome with the son of Pier Luigi Nervi, who was overseeing construction of the venues the firm had designed for the 1960 Olympics.

Upon his return to the United States, Horowitz worked for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill; Victor Gruen Associates; and Pomerance and Breines, where he was a project architect for New York University Hospital, before opening his own firm in 1972.

His work was varied, and he credits his Michigan connections with helping to bring in new clients and projects, including another lifelong friend, Fred Carcich, B.Arch ’60, whom he first met at Cooper Union and who followed him to Ann Arbor. Carcich later became a corporate project architect for American Airlines and commissioned Horowitz to design American Airlines Admirals Clubs at LaGuardia and JFK airports, as well as other American Airlines facilities in Puerto Rico and around the country. This led to projects for Eastern Airlines, Chase Manhattan Bank, the State of New York, and others.

“I’ve had some distinguished clients, and I owe that to the connections and prestige of Michigan,” Horowitz says.

American Airlines Admirals Club, LaGuardia Airport, New York.

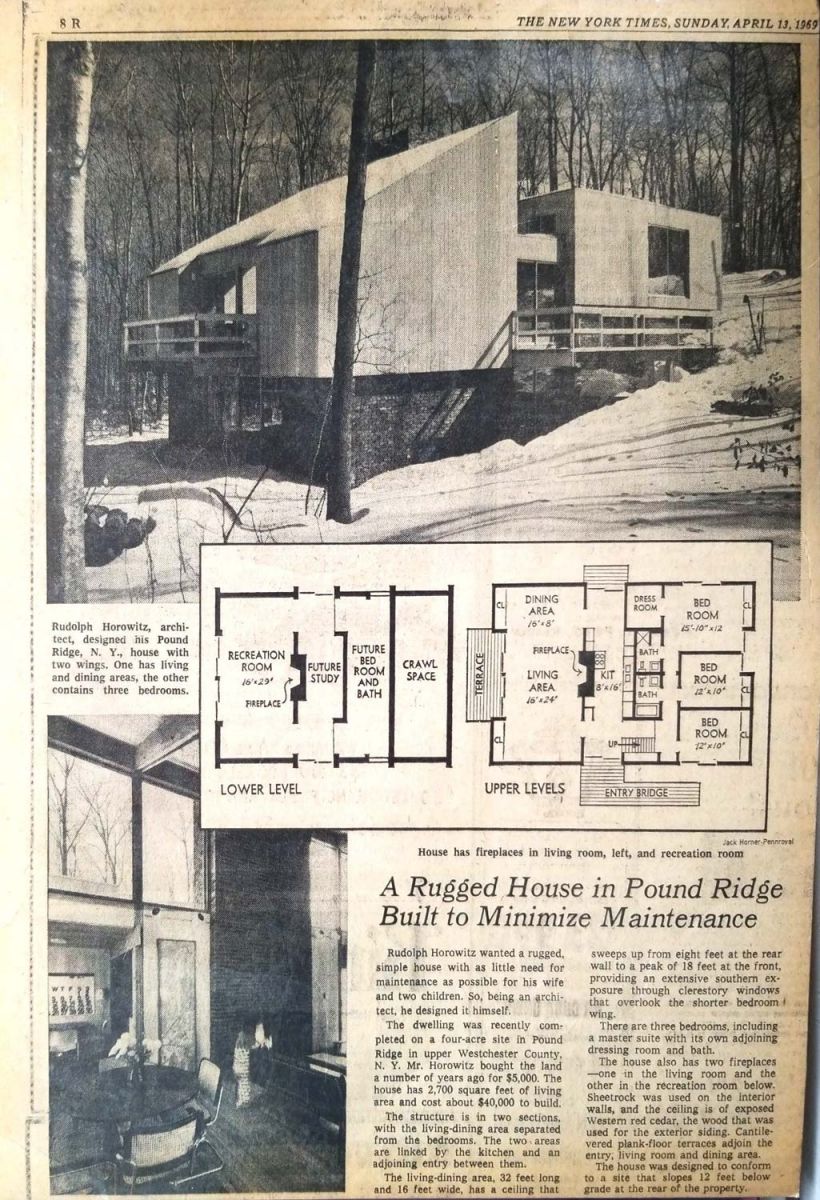

An April 13, 1969, New York Times story about Horowitz’s Pound Ridge, New York, residence.

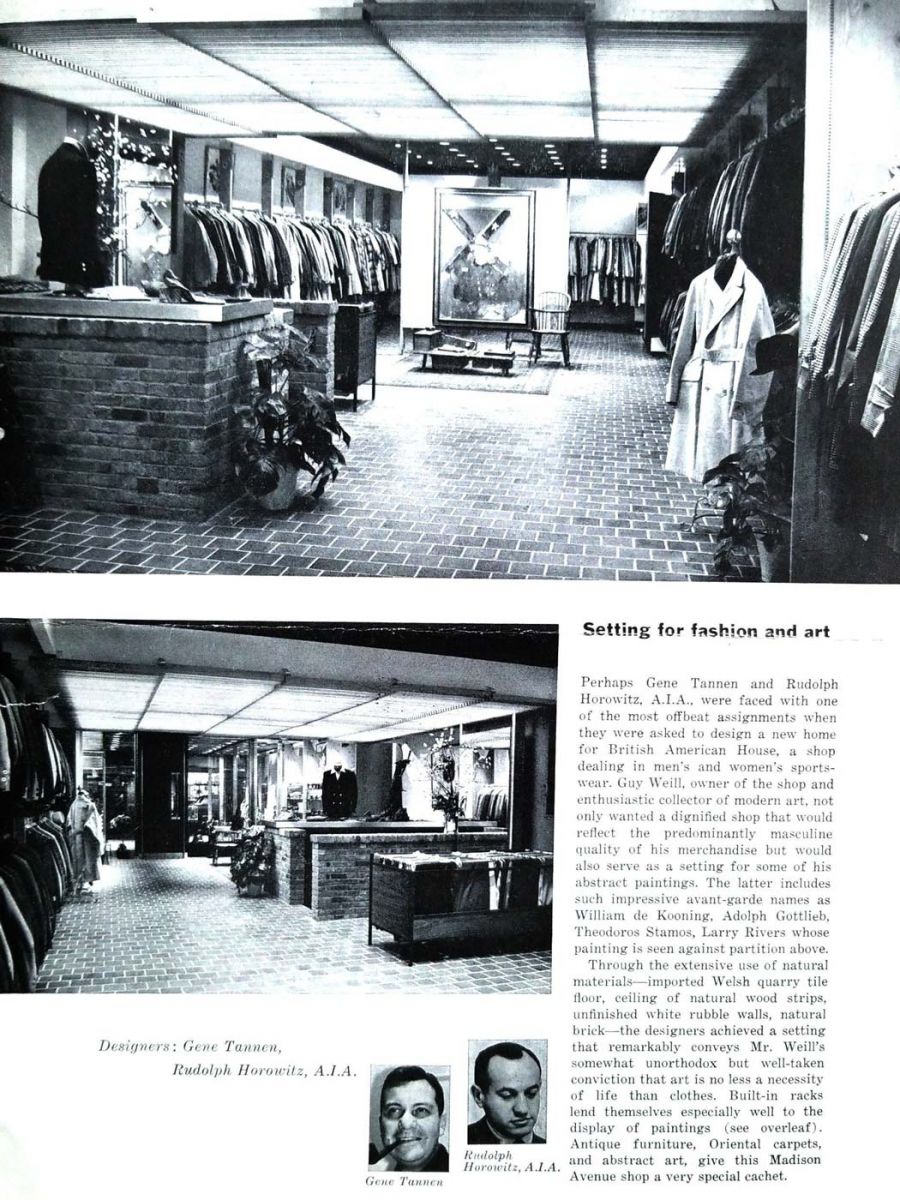

A portion of an Interiors Magazine feature about British American House, a Madison Avenue men’s store that Horowitz designed for Guy Weill, a modern art collector who displayed several works in the store.

With the development of computer-aided design in the early 1980s, Horowitz pivoted from practicing architecture to thinking about how architects could leverage this technology.

“I thought AutoCAD was ideal, and I wondered how we could adapt architecture to it, how pencil drafting could move to computers,” he says. Although he was in his fifties, he embraced the opportunity to learn the new technology and programming and then launched Geocad, an architectural application to AutoCAD. The program featured his hand lettering and stencils as fonts, making the CAD drawings appear hand drawn.

He marketed the entire system — including software computer and plotter — to architecture firms all over the country. He still keeps a folder of accolades he received, including from a client in Nebraska who in a 1985 letter called Horowitz “one of the best-kept secrets in the computer-aided drafting world … a brilliant architect who had the brains and guts to acquire computer knowledge and put together a system that is truly compatible with the way architects draw.”

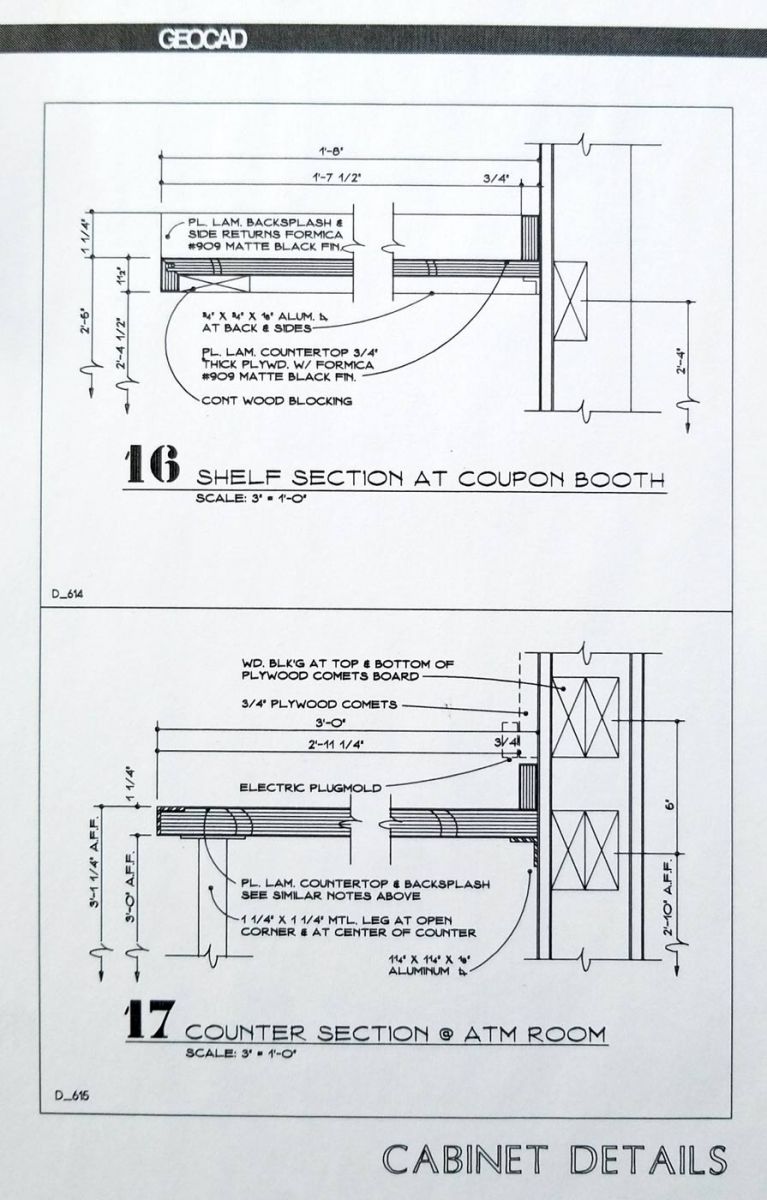

Geocad details featuring Horowitz’s hand lettering and stencil fonts.

Since stepping down from Geocad and his architectural practice in the early 2000s, Horowitz is enjoying retirement in Maine. He says that while the most tumultuous decade of his life, 1939 to 1949, doesn’t define him, he wants the recipients of those custom-designed birthday cakes, Oscar and Emma, to know his story. He wrote Avoiding the Cracks as a series of contemporaneous letters to his then-future grandchildren; royalties from the sales go toward their college education.

But his story is a lesson for all. “With people like me disappearing from the scene, and Holocaust denial and antisemitism growing again, we need to remember that the past is repeating itself all the time,” Horowitz says. “You must always remember the difference between what you are and who you are. What you are is an accident of birth. But who you are is the result of your surroundings, your parents, and mainly yourself.

“The great thing about this country is that when you come here, you can become who you want to be. I did.”

In retirement, Horowitz has turned his design talents to baking, including cakes for his grandchildren’s birthdays.