Much of Lesli Hoey’s research was inspired by growing up in a remote part of Bolivia where her father ran a cooperative farm. “They were practicing fairly forward-thinking sustainable agriculture strategies in the tropics,” she says.

Hoey, an associate professor of urban and regional planning, has dedicated her academic career to studying the adverse consequences of unequal access to healthy food and ways to address the problem. She experienced the challenges firsthand as a young child, when her family moved to the U.S. and lived in her grandparents’ trailer in western Pennsylvania. Being poor, she experienced the consequences of food inequality and the role of government food aid that she says provided mostly unhealthy options: “There were huge chunks of cheese, dehydrated milk, canned goods and boxed food,” she says.

This was in stark contrast to Bolivia, where her family lived on fresh, healthy, unprocessed food.

A turning point was in 2003, when Hoey spent nine months at a working ranch in Arkansas that was part of a small nongovernmental organization called Heifer International. She taught students about global hunger and poverty and strategies for changing the food system. “It solidified that this is what I want to do — be a part of creating solutions for global hunger and poverty.” Transforming food systems, she says, not only addresses issues of economics and equity but also has “incredible impacts on environmental resilience and people’s health and nutrition.”

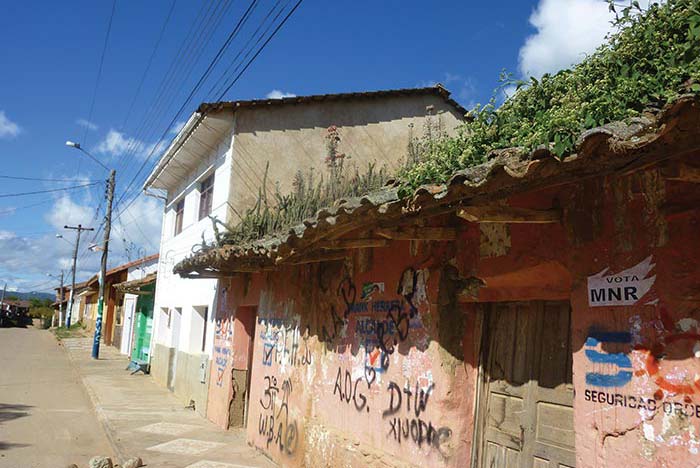

She’ll now have the opportunity to further this work as a Fulbright Fellow, examining how Bolivia’s Promotion of Health Food Law affects urban food systems planning. In 2022, she’ll spend three months in Bolivia looking at how street food vendors impact the nutritional value of food offered in urban schools. In low- and middle-income countries, street vendors often are vilified or violently attacked by local governments that have a vision of modernizing and cleaning up the streets. “Cities have a myopic view. They think supermarkets will solve food security and increase the prestige of their city,” Hoey says. Yet the result often undermines food security and worsens the job prospects “of so many of the working poor.”

Hoey will study how a collaboration with street vendors in the Bolivian municipality of Montero is promoting access to more nutritional food.

Street vendors in urban areas in Bolivia congregate around schools, selling food in the morning and at lunchtime. Because they had been offering less healthy options like chips, candy, and fried and processed foods, Hoey says they distracted children away from the healthier meals they receive in the schools. As part of a six-year pilot project, the municipality worked with street vendors to develop and test menus with healthy food options. It also mobilized others to show there was a demand for healthier food. This set the vendors up for success in selling the healthier items, she says.

Through a Fulbright Fellowship, Hoey will study how a collaboration with street vendors in Bolivia is promoting access to more nutritious food.

Her goal with her research project is not just to develop plans, but measures for implementing them. She wants to study the way the collaborative process succeeded in convincing street vendors to change their offerings. She says that’s critical for building the capacity of other municipalities to begin to change their food environments. And it provides a mechanism for other cities around the world that are trying to follow this model. “I want to show how informal food vendors actually are part of the solution that they’re trying to achieve,” she explains.

Hoey brings her expertise to Taubman College students, teaching graduate courses in food systems policy and international development planning. As part of a campuswide cluster of faculty focused on sustainable food systems, she collaborates on teaching and research through U-M’s Poverty Solutions Initiative and other partnerships. Since few urban planning scholars focus on food systems, “I don’t fit that traditional mold,” she says. “Being able to teach classes that are so fundamentally wrapped up with everything that I do in my research enhances my research, too.”

Going forward, Hoey is interested in exploring the long-term impact of COVID-19 on food systems. She believes that the pandemic could provide an opportunity for “transforming our food systems in fundamental ways.” She points to detrimental impacts resulting from restaurant closures, disruptions to grocery store food chains, and significant COVID exposure at meat packing plants: “All of it is really making people recognize that there’s so much about our food system that is failing our environment, and our health, and many people’s livelihoods.”

In the U.S. and globally, small-scale farmers have rallied by developing innovative approaches for direct sales, delivery methods, and online ordering, she says: “So it’s a really critical moment.”

— Julie Halpert