By Amy Spooner

Sowing Fertile Ground

When Travis Crabtree looks around his new hometown of Jackson, Mississippi, he sees opportunity — opportunity to rethink automobile infrastructure and industrial infrastructure. And with his partner, Salam Rida, he has gone all-in on seizing it. Among their numerous projects since moving to the city not even two years ago, the pair have reimagined a 15,000- square-foot crumbling industrial warehouse as a closed-loop incubator for sustainable food systems, a decrepit bridge as a community greenspace, and streets as parks.His thinking about adaptive reuse of infrastructure developed during his studios at Taubman College, says Crabtree, M.U.D. ’16, senior urban planner for the City of Jackson.

“It was definitely a theme. My studios focused on the future of post-industrial cities through working in various parts of Detroit,” says Crabtree, who also highlights the importance of traveling through Germany’s Ruhr region with Associate Professor María Arquero de Alarcón’s studio. “The Ruhr was once one of the most industrialized and polluted parts of the world. Our research there explored how industrial artifacts could be reprogrammed and landscape design interventions could energize and humanize a region that was once designed only for industry. That period we spent in the Ruhr is extremely influential in my work today,” he says.

(Top) Crabtree and Rida at the Ecoshed. (Bottom) Crabtree calls parklets “an example of how tactical urbanism can transform a street into a better human experience.”

Together with Rida, B.S. ’11, M.Arch ’17, an urban designer for the City of Jackson, Crabtree is spearheading a vision of making the city more equitable and human scale, drawing parallels from his student days in the Rust Belt. “Similar to Detroit, Jackson is not a human-scale city,” says Crabtree, a native of Mississippi. Nearly all residents drive everywhere, putting stress on roads and exposing the city’s flawed development plan. In 2018, Crabtree and Rida led Jackson’s successful bid for a $1 million grant from the Federal Transit Authority to plan and develop ONELINE, a five-mile, multimodal public transportation corridor. Since crumbling infrastructure and a lack of repair funds have closed many city bridges to car traffic, Rida and Crabtree are involved in conversation with a community about transforming one of those bridges into a neighborhood park. They also developed Mississippi’s first parklet, which Crabtree describes as “an example of how tactical urbanism can transform a street into a better human experience. When we moved to Jackson, we immediately started thinking about how current mobility patterns and food systems are contributing to the city’s quality of life,” he says.

“Salam, Travis, and their team have conceived a very forward-looking, innovative approach to engaging people with diverse perspectives and capacities to explore linkages between food and health as a form of urban transformation.”

— Associate Professor Geoffrey Thün

They found a close negative correlation in Jackson. The city is a food swamp, meaning the most readily available food is the high-calorie and low-nutrient offerings in the ubiquitous fast-food chains and convenience stores. Combined with the sedentary reliance on automobiles, Jackson has the dubious honor of being one of America’s fattest cities. “We’re looking at food access through the lens of urbanism and the urban scale and trying to inspire dialogue about cities’ roles in providing better food access for their people,” says Rida.

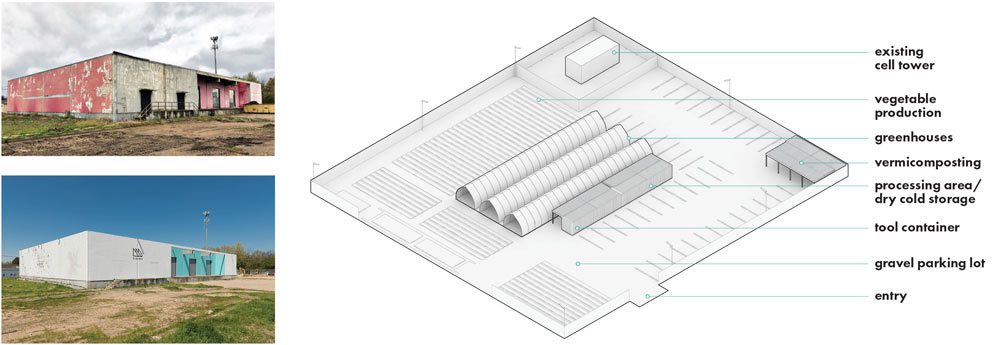

Through their practice, Carbon Office, Rida and Crabtree are developing a former industrial building into a mixed-use incubator space known as the Ecoshed. Conceived as a closed-loop food system, the Ecoshed’s tenants include an urban farmer who farms small parcels; an entrepreneur who uses worms to transform food waste into fresh, high-nutrient soil; and Nick Wallace, the first chef from Mississippi to win Food Network’s Chopped championship, who will operate a “food lab” that trains local chefs in farm-to-table cooking. Crabtree and Rida’s former Taubman College professors Geoffrey Thün and Kathy Velikov — with whom Crabtree worked after graduation at their firm, RVTR — advised on the project; they also have signed on to be part of Rida and Crabtree’s larger effort, “Fertile Ground: Inspiring Dialogue about Food Access.” The city-wide exhibition in Jackson will feature installations, performances, and programming that aims to inform policy related to nutrition by using art as a medium to communicate the complexities of the issue in the city. The project, which includes the Ecoshed as an anchor site, received a $1 million Bloomberg Philanthropies Public Art Challenge Award in late 2018. Rida is serving as Fertile Ground’s curator.

Before and after photos of the Ecoshed, part of “Fertile Ground: Inspiring Dialogue About Food Access,” which recently won a $1 million grant to inform policy related to nutrition by using art as a medium to communicate the complexities of the issue in Jackson. (Right) Organic Urban Farm.

“Salam, Travis, and their team have conceived a very forward-looking, innovative approach to engaging people with diverse perspectives and capacities to explore linkages between food and health as a form of urban transformation — and we are excited to be part of it,” say Thün and Velikov, whose installation will highlight food production and high-tech food systems. “And they have bottomless energy, charisma, and curatorial sass,” adds Professor Anya Sirota, whose firm, Akoaki, which designed the Oakland Avenue Urban Farm in Detroit, is designing a consumption-themed installation for Fertile Ground.

“When you traditionally talk about food access, people ask how art is part of it,” says Rida. “But our experiences at Taubman College and our work with our professors showed us that when you think more fluidly about what art is, you can create new scenographies to explore unconventional urban interventions.”

Getting buy-in early and often from the community also is important because it allows everyone to see the value of that fluidity, Rida notes. “One of the main aspects of my education that informs my work today involves exposing the process and system of design work, as opposed to only celebrating the ‘final’ or ‘finished’ product. This way, architecture becomes accessible in its various forms and the public can learn about what we do and how they are involved in the structure of the built environment.”

Reimagining Housing

engaging the community through their work is central to architecture students’ experience, especially for students in the Master of Architecture program’s Systems Studio, which was revamped in recent years to focus on various aspects of housing in Detroit.

The Systems Studio relaunched in fall 2016 after a series of “what if?” conversations among Professor Sharon Haar, the chair of the architecture program; City of Detroit Planning Director Maurice Cox; and Lars Gräbner, a professor of practice who also leads Detroit-based firm VolumeOne with Christina Hansen, a lecturer. With a city-wide renaissance underway, Detroit was undergoing massive, multifaceted redevelopment, much of it focused on local neighborhoods. Cox and his staff wanted students to reimagine sites that the city identified as priorities. Their goals were to spark innovation among prospective developers and start a discourse of what inclusive housing can look like for future generations of Detroiters, how changing lifestyles can be sustainably integrated in new neighborhood developments, and how innovative development in Detroit can serve as an inspiration for other American cities. They also wanted to build a culture of design in the city. “The Systems Studio is about inspiring solutions that elevate the status quo for housing in Detroit,” says Gräbner. “In recent years, the status quo has been low. Architecture hasn’t been important because there are so many other issues facing the city. But we are working with our students to change that.”

Work from M.Arch Systems Studio students was featured as part of the biennial Detroit Design 139 exhibition in 2017.

About 150 students take the Systems Studio each year, working with around 13 faculty in several districts throughout Detroit. Teams develop design proposals for housing sites selected from the Detroit Planning and Development Department master list and focus on a specific design challenge like senior living, multigenerational housing, live-work environments, healthy living, or cooperative housing. The teams create comprehensive urban and building strategies, from initial analysis to early-phase design development; internal and external faculty, practicing architects, and representatives from the Detroit Planning and Development Department then review the plans. Eight designs from the studio’s first year were selected for inclusion in “A City for All: Future Housing Models for the City of Detroit” — a biennial public exhibition co-sponsored by the city and real estate firm Bedrock as part of Detroit Design 139, a coalition of business, education, and nonprofits that promotes equity, design excellence, and inclusion. The exhibit’s concluding symposium featured the students’ work as the basis for discussion. “Their work is visionary yet realistic and gives the public a sense of what’s possible,” Gräbner says. “And because the work of architects, non-architects, students, and non-students was exhibited together, it was an incredible opportunity for our students to showcase their ideas and invite critique before a real-world audience.”

Being able to watch the public study his project was indeed a coming-of-age moment, says Masataka Yoshikawa, M.Arch ’17, who was part of the Sky Bar team that was included in the Detroit Design 139 exhibition. “People were talking about it and taking pictures of it. Our design was very different from what Detroiters are used to seeing,” he says. In designing Sky Bar, which Yoshikawa and his classmates dubbed “Detroit’s iconic gateway,” they elected to elevate the residential building in order to optimize circulation and recreational use of the landscape, as well as provide future development opportunities. “It was interesting to present to city officials and others who live in Detroit — many for their whole lives — and to hear them say, ‘I hadn’t thought about it that way before,’” says Yoshikawa, a native of Japan who had never visited Detroit prior to attending Taubman College.

He participated in Gräbner’s studio — co-taught with Hansen — which tasked students with designing a housing development near the Dequindre Cut, a two-mile-long greenway that opened in 2009 and offers a pedestrian link between several neighborhoods and community landmarks. “I was interested in the sites in Lars and Christina’s studio because these communities were bisected by major highways and other infrastructure and now are being reconnected by the Dequindre Cut,” says Yoshikawa, whose team chose a site along Gratiot Avenue, overlooking the popular Eastern Market and iconic Lafayette Building, for their Sky Bar concept. “Where I grew up, there were singular communities, but Detroit’s neighborhoods have distinct identities and histories and a strong sense of pride. Architects have to balance honoring that tradition while being innovative.” He also appreciated that Gräbner and Hansen’s holistic approach encouraged students to not just focus on an eye-catching concept but to emphasize the structural and environmental aspects that “made us approach and analyze our designs from multiple directions.”

“Students who participate learn not only how to design exquisite buildings but how to have an impact in their work and how to serve the public interest.”

— Maurice Cox, City of Detroit

The studio also was a unique opportunity for Yoshikawa, who now is an architect at PLY+ in Ann Arbor, to understand how to work with a different kind of client. “I learned that working with a community is not like working for a company that has a specific set of requirements. In a community, different people want different things and see things in different ways, so my approach has to be organic.” Understanding those nuances is an important goal of the Systems Studio, Haar notes. “A major point of the collaboration is that in working with the Planning and Development Department, our students become more aware of the interests and needs of the city and its citizens.”

The Systems Studio also exemplifies how a leading university can serve as an idea generator and the means for igniting positive change, Haar says. “It is an excellent instance of architecture research and design at a world-renowned university being driven toward community need. In addition to teaching students the value of research in architectural design, we are demonstrating how their work can impact contemporary rebuilding in a major American city. Our student teams generate pre-design thinking that typically doesn’t happen in spaces like these, and we present multiple ideas for individual sites. As a result, this studio is a catalyst for broader, deeper, bolder thinking on the part of practicing architects throughout the City of Detroit.”

Cox, whom Gräbner describes as “closely involved” with the studio and the students’ work, agrees: “Students who participate learn not only how to design exquisite buildings but how to have an impact in their work and how to serve the public interest. There is no better relationship with a college of architecture and urban planning than that of U-M and Detroit.”

Bridging Business

During a networking reception in Detroit on a cold February night, the Michigan Hispanic Chamber’s CEO chatted with Ryan Michael about the chamber’s effort to build a statewide, Latino-based contracting association. “I told him I used to do that with Paving the Way,” says Michael, M.U.P. ’10. “He said that was the project they were working with, and I replied, ‘I helped write the plan to launch it.’”

Ryan Michael, M.U.P. ’10, stands near the future site of the Gordie Howe International Bridge.

It was a coming-full-circle moment for Michael. As director of Pure Michigan Business Connect, part of the Michigan Economic Development Corporation, he helps Michigan-based companies get the necessary tools and access to compete for global business opportunities. The roots of his work stem from his student days in Eric Dueweke and Margaret Dewar’s urban and regional planning capstone studio. In “Paving the Way: Linking Southwest Detroit to Infrastructure Jobs,” the Southwest Detroit Business Association (SDBA) asked Michael and his classmates to study the neighborhoods affected by two proposed infrastructure projects: the Detroit River International Crossing — a new bridge between Detroit and Windsor, Ontario, now known as the Gordie Howe International Bridge — and the expansion of the Detroit Intermodal Freight Terminal. The team proposed ways to help southwest Detroiters access construction jobs related to the projects, as well as long-term employment in jobs associated with their ongoing operation.

The capstone — which won the 2011 Outstanding Student Project Award from the Michigan Association of Planning — was a natural bridge from Michael’s AmeriCorps work the previous summer with the SDBA. Then he returned to SDBA after graduation to launch Paving the Way as a job connector, before moving to the Detroit Regional Chamber to help establish the operating model for the Connection Point program, which eventually merged with Pure Michigan Business Connect and led to his current work. “I love my job, and my ability to be here stems from my experience at Taubman College,” Michael says. “Through my capstone, I learned how to consider how the voices of the many and the voices of the few can interact for a suitable outcome.”

“Through my capstone, I learned how to consider how the voices of the many and the voices of the few can interact for a suitable outcome.”

— Ryan Michael, M.U.P. ’10

While Michael’s capstone experience helped launch his career, it also provided the SDBA with workable recommendations. That dichotomy is exactly the point, says Dueweke, who has led more than 50 urban and regional planning capstones during his tenure at Taubman College, including many in Detroit: “We’re simulating the real world of planning, and when students leave, clients have steps they can take right away, without much cost, to effect change. It’s exciting for the students and the organizations.” An experiential project — either a group capstone studio or an individual thesis — is required in a planning student’s final year. Recent projects include expanding a bike-sharing program in the Detroit suburbs; developing a neighborhood plan in Flint, Michigan; and designing an Allen Creek Greenway in Ann Arbor. In 2018, “Stabilizing MorningSide,” which addressed housing concerns in a Detroit neighborhood hurt by mortgage and property tax foreclosures, won a nationwide award from the American Institute of Certified Planners. “Through our capstones, students can put what they’ve learned to use in service of a client that desperately needs their expertise,” says Joe Grengs, associate professor of urban and regional planning and program chair. “It speaks to the heart of who we are as a public university and as a profession, while providing experience and connections that cannot be replicated in the classroom.”

Gathering community input was an important part of Michael’s work with his capstone and after graduation.

With “Paving the Way,” in addition to the job connector program that Michael went on to launch, students analyzed the proposed expansion of the freight terminal in the context of the broader transportation infrastructure in Southwest Detroit. They recommended establishing a strong working relationship with the Michigan Department of Transportation, the state’s vehicle for implementation. “The students helped the community learn how to leverage its standing,” says Kathy Wendler, former executive director of the SDBA, the client for “Paving the Way.” Another less tangible but important outcome: goodwill and neighborhood pride. “What impressed the community about the students’ work was their clear assumption that the community had a role to play,” says Wendler. “The lasting value of the university’s engagement is its corporate memory of the Southwest Detroit community and our progress toward true community benefit.” The college continues to work in the neighborhood — a winter 2019 capstone led by Dueweke and Professor Jonathan Levine explored ways to mitigate the increased noise and air pollution that will be generated by traffic from the Gordie Howe International Bridge, which is scheduled

to open in 2024.

“Traveling to Detroit multiple times a week, seeing the faces of the potentially displaced people, seeing the contractors and knowing what they could do with the right opportunities makes homework become real-life work,” Michael says. “It takes on a different meaning.”

Linda Fitzgerald contributed to this story.