By Amy Crawford, Julia Broadway, and Amy Spooner

When Dean Jonathan Massey adopted “don’t go back to normal” as a mantra in the spring, he was thinking about the necessary transformations in education that were accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Just a few months later, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police sparked worldwide outrage and forced Americans — and Taubman College — to grapple with the origins and consequences of deep-seated systemic racism.

“Don’t go back to normal” is now an apt rallying cry for a college at a crossroads in the wake of 2020’s monumental events. How do we embrace the changes necessitated by the pandemic in order to make lasting changes to the way we deliver education, in order to make it more inclusive? And how do we ensure that our community and our curriculum reflect the diversity of the world that we serve as planners, architects, and citizens?

As you’ll read below, students are working alongside administrators to find answers.

Advancing Racial Equity

Many professions play a role in shaping communities for better or worse, but few have as visible an impact as architects and urban planners. That weighty responsibility is always on Serena Brewer’s mind and came to a head when a studio course project took on the adaptive reuse of a building in her hometown.

“It was a theater in a neighborhood in Chicago that was predominantly Latinx,” explains Brewer, M.Arch ’21. “Only a few of us were focusing directly on that community makeup, even though it’s integral to the neighborhood. We felt that it would be remiss not to consider the artistic development of people who are already there, and to integrate the architecture of whatever we’re proposing into the community. We were worried about gentrifying the space.”

Brewer and her classmates recognized that they had a moral duty to consider the context of buildings and planning projects, especially when a marginalized community seeks to preserve its culture and prevent its history from being erased. “I feel that’s lacking in our education sometimes,” she says, “and it needs to be addressed at the beginning of the project, before you take on any of the other design aspects.”

The nagging discomfort that Brewer had felt in the course, as well as issues that were arising for her fellow students of color, remained at the forefront of her mind as the COVID-19 pandemic forced U-M to hold classes online last spring — and, later, as Black Lives Matter protesters rose up against police brutality in cities around the globe. It was a historic moment, and Brewer and many of her fellow students saw in it an opportunity to fight for racial justice closer to home. Out of their conservations grew a student-led movement, Design Justice Actions, which is pushing Taubman College — and by extension, the professions of architecture and planning — toward a more just and inclusive future.

“Students — mostly students of color — had been doing social justice work for a long time,” says Joana Dos Santos, Taubman College’s chief diversity, equity and inclusion officer, whose job is to partner with students, faculty, and staff in efforts to make the college more inclusive of people with different racial, ethnic, and gender identities. “But there are still few students of color in our school, and sometimes their voices were drowned out.”

According to a report assembled by Dos Santos’s office last year, less than 11 percent of students identified as members of underrepresented minorities (Black, Indigenous, or Latinx), along with 17 percent of staff and just under 12 percent of faculty. Those numbers are far lower than figures for the state of Michigan and the nation as a whole, and they can make for a lonely experience for students whose backgrounds are different from the vast majority of their peers. It’s not just a Taubman College problem: studies by the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture and the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards show that the discipline of architecture is marked by gaps in participation and advancement by gender and ethnicity, leading to a profession with pronounced disparities. These disparities begin at many accredited U.S. architecture programs, where the student body often skews toward white, male, and able-bodied people from affluent families.

“It’s definitely difficult being a student of color at Taubman, just because you’re few and far between,” Brewer says, “but it’s not unlike many other schools of architecture across the country.”

During the Black Lives Matter protests in June, Dean Jonathan Massey hosted a virtual town hall, open to the entire college, including alumni. The agenda was put together in partnership with students, faculty, and staff of color, mostly Black. “It was very clear, as a community, that we understood that we needed to do something about racial justice and anti-racism,” Dos Santos says.

The town hall exposed deep pain and outrage that was difficult but motivating.

“This is a time of compounded pain stemming from multiple traumas: not only police killings and repression of public protest,” says Massey, “but also the disparate impact of COVID on communities of color in and beyond Michigan. Our students, staff, faculty, and alumni are among those generating knowledge about structural racism and creating tools for promoting spatial justice, so personal pain and outrage is often linked to our intellectual and professional work. It was painful for me, and I think for most participants, to hear from our colleagues about the extent to which structural racism has affected them in the world and on our campus. This was also an essential step, though, in identifying the work we must do now.”

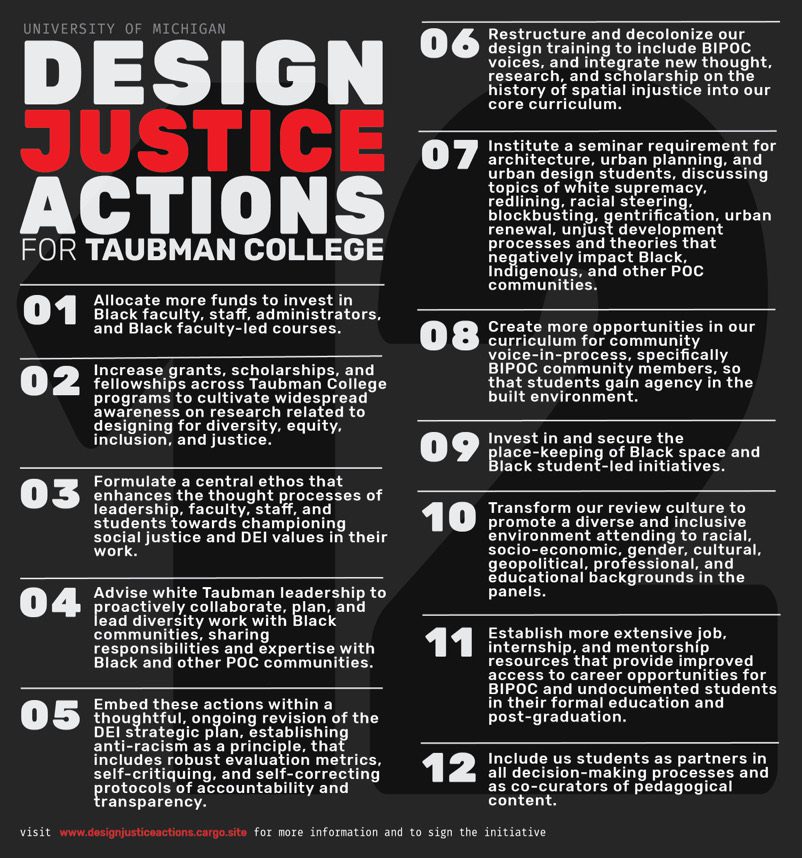

As part of a national movement, in June, students outlined 12 Design Justice Actions to address inequities at Taubman College.

In the wake of the town hall, Brewer was approached by her friend Emily Ebersol, M.Arch ’21, who is white, and they moved quickly to create Design Justice Actions. Ebersol says that early in her academic career she was “exposed to some incredible people in the field of architecture and design who were at the forefront of these conversations,” so as she watched events unfold in Minneapolis and elsewhere this summer, “I always go back to this quote from Lilla Watson that says, ‘If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.’”

Brewer and Ebersol were soon joined by a few dozen other students, along with faculty and staff advisors. Their subsequent letter to college leadership was a true group effort, says Ebersol. “We had a document that was open for community edit — a huge Google doc where everyone could contribute ideas.” Out of that process emerged 12 short-term and long-term demands, which the students listed in a June 22nd letter to the college’s administration and faculty that has so far been signed by more than 200 members of the Taubman community. The demands aimed not only to create a more welcoming campus environment for students of color but to reimagine architecture and urban planning education in a way that would help Taubman graduates work toward racial justice and better serve diverse communities in the 21st century.

“The existing pedagogies, curriculum, and general instruction of these disciplines were bred out of outdated social, cultural, and economic structures and have failed to fully evolve with society,” the students wrote. “Our education impacts our ability to seek justice in our professions and the communities we shape. For Taubman College to promote public good through academic excellence and ‘build tomorrow,’ we must first rebuild our foundations from within.”

Of the 12 demands, five are earmarked as early priorities, based on their potential for quick action, as opposed to demands like increased hiring of faculty of color, for example, which take longer to execute and are more dependent on external factors. Each of the five priority actions has a dedicated working group of students, faculty, and staff who are further researching, investigating, and reforming the existing structures of that point.

The five priority actions are to embed these actions within a revised DEI strategic plan that establishes anti-racism as a principle; to include BIPOC voices and the history of spatial injustice in the core curriculum; to institute a seminar requirement for all Taubman College students that discusses unjust development processes and theories that negatively impact BIPOC communities; to create more curricular opportunities for BIPOC community voice-in-process so that students gain agency in the built environment; and to transform the college’s review culture to promote a diverse and inclusive environment in the panels.

The students’ final list of demands, Ebersol says, was heavily influenced by Design as Protest, a nationwide coalition of designers that, in its own words, works to “dismantle the privilege and power structures that use architecture and design as tools of oppression” and envisions “racial, social, and cultural reparation through the process and outcomes of design.” With these ultimate goals in mind, the Taubman students sought more funding to invest in Black faculty, staff, and leadership, as well as for grants, scholarships, and fellowships geared toward diversity, equity, and inclusion. They asked the college to “formulate a central ethos” that aimed toward social justice and requested that white administrators not only collaborate with Black communities and people of color but also proactively lead anti-racism efforts. And they sought a curriculum that would integrate not only the voices of people of color and community stakeholders but also examine the ways in which design has historically contributed to injustice.

“It’s important to get the knowledge of practices like redlining and urban renewal, which have undermined people of color, into the minds of young architects and planners,” Brewer says. “These things are really crucial to how you work in cities, and how you deal with the built environment in general.”

Brewer and Ebersol got to know each other last fall, when both took a class on design activism and social justice with lecturer Craig Wilkins. An award-winning Black architect who serves as creative director of the Wilkins Project, which provides architecture and urban planning services for projects that further social justice goals in Detroit, Wilkins helped students explore ways in which what is taught — or not taught — can influence whether design is effectively racist or anti-racist.

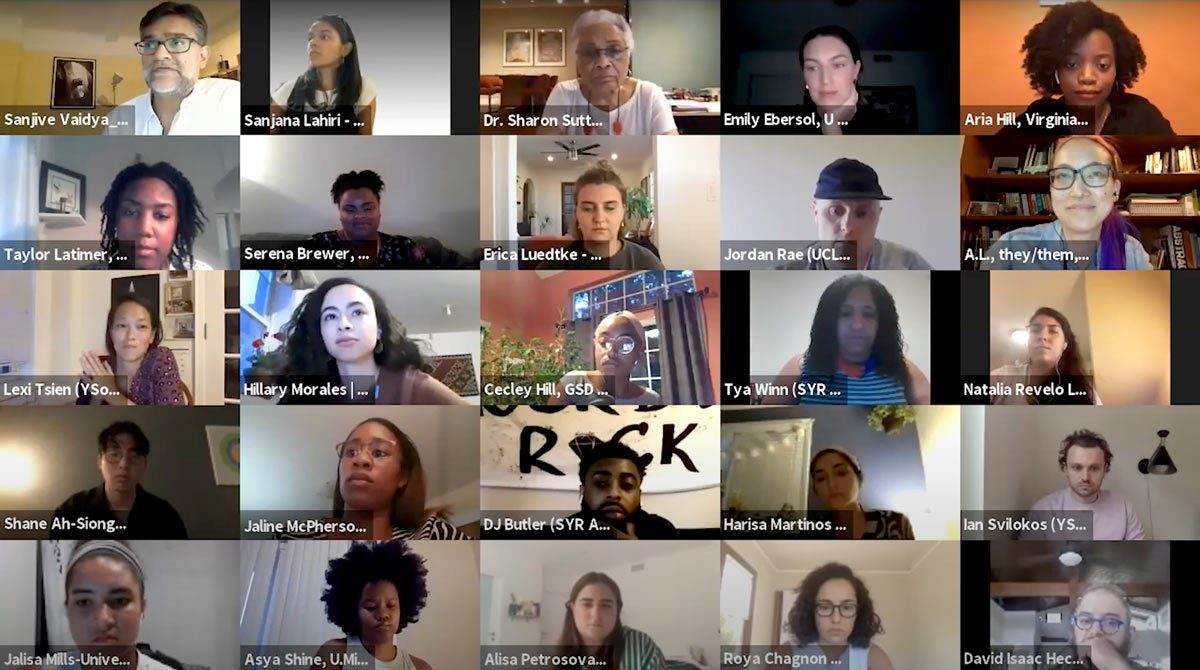

Serena Brewer (second row) and Emily Ebersol (top row) participated in “New Grounds for Design Education” with students from other leading schools in July.

“The course is specifically designed to catalyze thinking about the discipline and profession and how students might shape careers in ways that address issues most concerning to them,” says Wilkins. “Inherent in that search is not only an interrogation of the structures that prevent a full blossoming of such agency in the academy, the profession, and the built environment but also serious and sustained discussions with peers about how such frameworks might be reimagined.”

He adds that he is “not at all surprised” that Brewer and Ebersol are leading Design Justice Actions efforts: “They were part of a particularly engaged and highly motivated cohort last fall, deeply connected to the larger justice movement across the country. It was a joy to learn with them then and remains so today.”

“We did a lot of critical thinking in that course,” Ebersol says, explaining that the work of Design Justice Actions, although energized by a larger societal shift, is building on an effort that was already underway at Taubman, through courses like Wilkins’s as well as the school’s strategic plan for diversity, equity, and inclusion, now in its fifth year. “There are so many people that have been working on design justice for years — we’re by no means the beginning of these conversations.”

That meant that the institution was receptive to Design Justice Action’s agenda, and faculty and staff quickly joined student-led work groups to begin addressing the demands. Over the summer, they developed a process that would help faculty review their syllabi and figure out ways to broaden the long-standing canon of white male architects, planners, and designers. They also meet with the college’s alumni relations team to brainstorm ways to get alumni involved, whether by supporting Design Justice Actions’ work financially, mentoring the group’s student leaders, writing articles for the new biweekly newsletter, Racism Review, or speaking about racial justice on campus.

“Taubman alum Christopher Locke was involved from the beginning and helped shape and energize the Design Justice Actions you see today. We are looking to widen our involvement in this initiative, especially to include more alumni,” Ebersol says.

Meanwhile, Dos Santos led a weeklong racial equity workshop to help students, as well as faculty and staff, think through the ways in which they could bring anti-racism not only into their classrooms, but into their lives.

“We are trying to expand the lens by which we teach and work,” Dos Santos says. “For architecture and planning, this is mostly a white male lens. The goal is to add other lenses by unlearning some of the harmful aspects of architecture and planning and learning new lenses that can bring a more holistic approach to the built environment. We need to add lenses from people of color, women, people with disabilities, and other marginalized groups that may not be represented in the fields.”

The positive response from faculty, administrators, and other members of the Taubman community has been gratifying, the students report. And although the changes they are seeking will take years of work, by fall the atmosphere on campus had already shifted. In a reprise of her first semester at Taubman, Brewer is working on another Chicago project for a studio course. This time, however, the whole class had to treat community, identity, and context as foundational.

“We did a deep dive into the cultural, racial background of the neighborhood that we’re working in,” Brewer says. “In any city, every neighborhood has a long history like that, and it’s important to understand that, to be able to provide a solution to a societal and/or environmental problem. And that’s what architecture does, right? We build solutions.”

Creating Spaces for Collective Learning and Experience

If things were going according to plan, Ishan Pal, M.Arch ’20, would be in an office in Detroit right now, diving into post-graduation life at an architecture firm.

But by early March 2020, it was clear that in terms of well-laid plans, all bets were off — for Taubman College’s students and the professors who teach them.

So instead, Pal is helping Taubman College’s academic innovation team “try new things and new platforms,” including one that “has a huge potential to transform education,” he says.

Moving classes online in March because of the COVID-19 pandemic required faculty to “quickly translate the individualized, embodied, and immersive learning that Taubman College does best into a stop-gap measure for virtual delivery,” says Anya Sirota, associate dean for academic initiatives and associate professor of architecture.

Beyond the immediate crisis, the college recognized the need to build on new knowledge about the challenges and opportunities of going virtual.

“The beach” allowed students to safely gather this fall.

Adapting education within social distancing protocols and public health standards is extra difficult in design education, which relies heavily on collaborative, spontaneous, and interactive exchanges in studio and classroom environments. The college’s academic innovation team — led by Sirota, Jacob Comerci (academic innovation project manager), and Pal (Sirota’s former research assistant who signed on after graduation) — launched several grant programs, competitions, and cross-campus partnerships at the start of the summer.

The goal: maintaining the highest levels of academic excellence while advancing the conversation on what design education could look like in the pandemic and beyond.

“We saw an opportunity to innovate and create spaces for collective learning and experience, and to evolve our culture of place, given the challenges posed by the pandemic — and we recognized that our community needed to lead that innovation,” says Sirota. “We wanted faculty and students to drive a smarter, more nuanced, and more inclusive reentry strategy; at the same time, we wanted to ensure a continuity of our college’s culture and simultaneously engage as many people as possible in the co-creation of tools, methods, and strategies for a more humane and playful and engaged way of being together in this kind of space.”

Though the four design competitions and other initiatives had their own unique purpose and point of view, a unifying thread was the engagement and involvement of Taubman College students. In total, close to 25 percent of the student body participated in one or more initiatives, gaining opportunities to work and build their portfolios in a challenging time for employment and travel. The summer innovations also provided a roadmap for the future, says Comerci: “By calibrating our recent teaching and learning experiences to offer greater flexibility, social connection, and experimentation, they suggest an opportunity to combine in-person and dispersed learning scenarios in productive and liberating ways.”

One of the largest initiatives was Spatializing Digital Pedagogies, a grant program that invited students, alongside faculty and staff, to suggest ways the college can make the hybrid educational experience more compelling, either through utilizing existing tools or methodologies in a unique way, or building something entirely new to address the needs of distance learning.

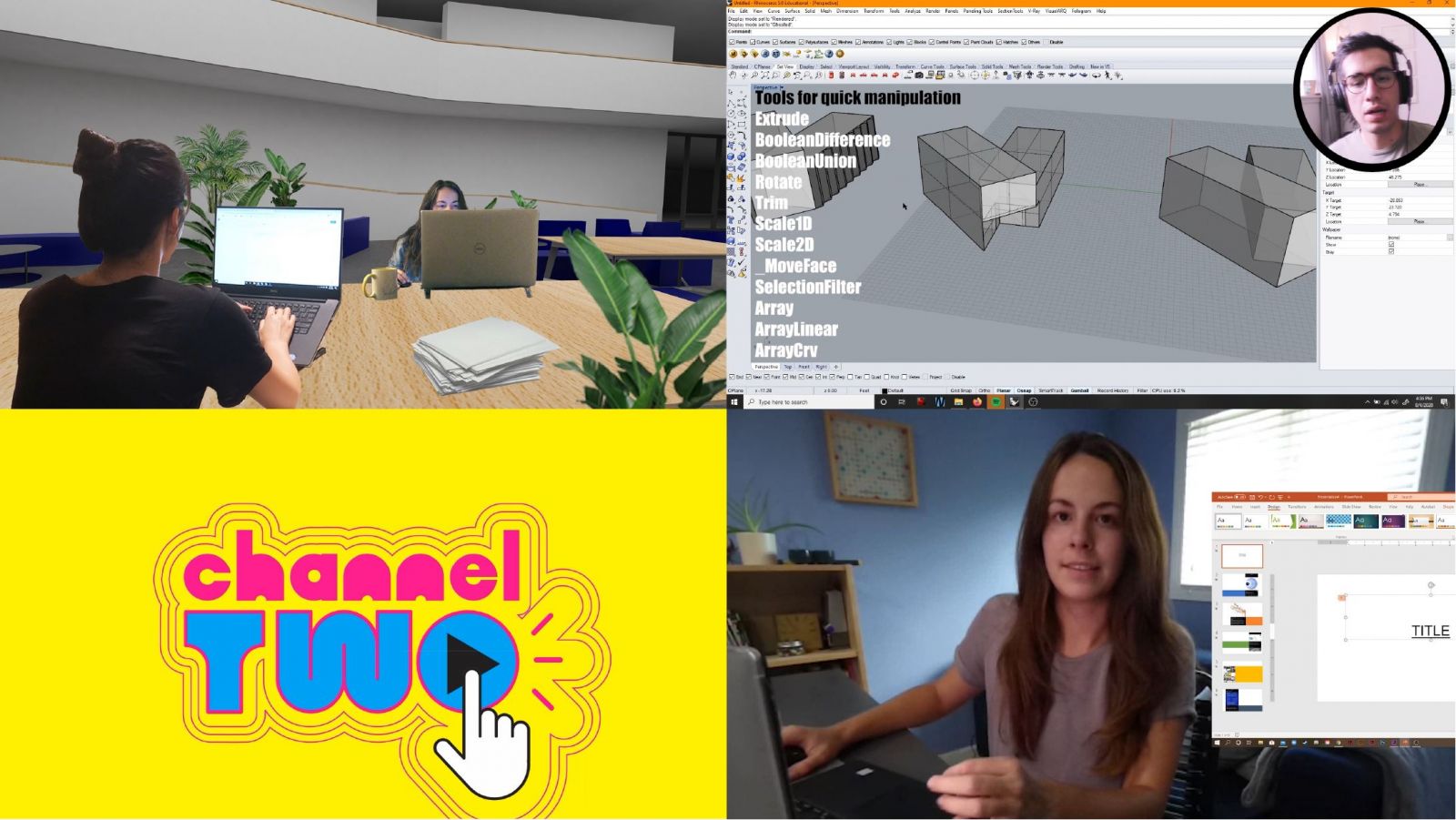

channel TWO is one of 10 Spatializing Digital Pedagogies grantees.

One of the 10 projects awarded funding is channel TWO (Taubman Workshop Online). Guided by faculty members Julia McMorrough and John McMorrough, a team of five M.Arch students sought to translate elements of Taubman College’s culture and student experience that would typically take place in the Art and Architecture building, to an on-screen format. The first phase is a series of videos for incoming students who are new to a design school environment. These videos can also fill gaps for continuing students who miss the daily in-person exchanges that take place throughout the college — in essence, helping to build a stronger sense of community and connection in the face of social distance. One set of videos, entitled “How to,” tackled normally impromptu discussions like “How to make a lot of study models” and “How to make your drawing come alive.”

“Not only did this project offer me work when opportunities were bleak, but it offered a chance to address the reason for opportunities being bleak: both academia and practice have long been dependent on communicating in person, and this project was born to initiate a rethinking of this apparent prerequisite,” says team member Tejashrii Shankar Raman, M.Arch ’21. “It has been insightful to be a part of a flagbearer initiative rooted in adaptability for changing times.”

“Our goal is to move from emergency remote instruction to resilient teaching, which sustains the imaginative discovery and peer-to-peer exchanges that enrich the design studio, but discards the challenges that traditional architecture education poses for many of our students — current and prospective.”

— Dean Jonathan Massey

Another Spatializing Digital Pedagogies project, “Rigging Videography,” considered how to teach fabrication and prototyping work to dispersed students and created a duo-perspective video cart that captures lectures and demonstration videos for both synchronous and asynchronous teaching. Led by Assistant Professor Tsz Yan Ng, a trio of digital and material technologies students developed the mobile recording studio, which they describe as “essentially a cooking show setup that promotes heuristic knowledge through making, an element that can be lost in remote teaching settings.” Since the video cart is webcam-ready, students can communicate live during Zoom calls to discuss their projects during remote desk crits. “It is about seeking to improve beyond what we are currently doing and being agile in adjusting to unexpected complex circumstances,” Ng says.

Along the way, Pal — the 2020 graduate who joined Sirota’s academic innovation team because “the work was going to be extremely creative and exciting” — has been providing technical support and design flair. He first helped launch the Taubman College Care Package, a series of online teaching tutorials for faculty. From there, he supported Spatializing Digital Pedagogies and the other summer competitions, including serving as emcee for their concluding awards ceremonies, which were streamed on Twitch and are archived on Taubman College’s academic innovation website.

Now his activities include beyond-Zoom lecture streaming. “Our goal is to make online lectures a lot more interesting than just sitting on a Zoom call,” he says. Pal has been working with Associate Professor Thom Moran to enhance lectures for the graduate architecture representation course; he also has been working with Eric Dueweke, lecturer in urban and regional planning, to digitize Dueweke’s annual bus tour of Detroit. In addition, he recently worked with Ellie Abrons and Meredith Miller, both associate professors of architecture, on an online lecture at the Cooper Union in which their avatars walked through virtual renderings of their work.

The duo-perspective video cart was created with a Spatializing Digital Pedagogies grant.

“People lose concentration on Zoom because it’s so static on a screen,” Pal says. “I want to push education to the level of movies or social media, where you get the feed at the rate that your brain wants it or needs it.”

Part of enhancing Taubman College’s digital community is giving it a hub. Launched just before final reviews in the spring, that’s the purpose of CMOK. Pronounced as an acronym, CMOK refers to the CMYK third-floor review space, one of Taubman College’s primary meeting spaces, and renders a hopeful message: “SEE-EM (I’M) – OK.” Associate Professors John McMorrough and Julia McMorrough came up with the title as a way to create empathy in the space between the real and the virtual.

“In an age of COVID-19 constraints, we conceived the online site as way to create a new space of connectivity, community, energy, intellectual cross-pollination, and serendipitous social encounters that are characteristic of our studio and commons spaces,” says Kathy Velikov, an associate professor of architecture who was part of the group leading the effort.

By leveraging web-rendering technology combined with map-like operability, the website looks more like a game than a collaboration platform. Users can pan through the virtual “city” of objects and furniture to see what is happening at Taubman College; they also could drop in to active studio webinars to hear the conversation or follow the links to website galleries. Each object presents the opportunity to join a different part of the Taubman community and participate in the work they are doing.

“In many ways, the modular and dynamically sortable space is a kind of calendar app. However, CMOK gives us something that calendars and emails cannot: a restored sense of place,” say Velikov and Oliver Popadich, M.Arch ’18, a Chicago-based designer, software developer, and engineer who was the site’s lead designer. “At a time punctuated by grids of floating heads, moving through the site’s landscape offers a sense that another big thing is happening just around the corner, and that all are invited to partake in the buzz at Taubman College.”

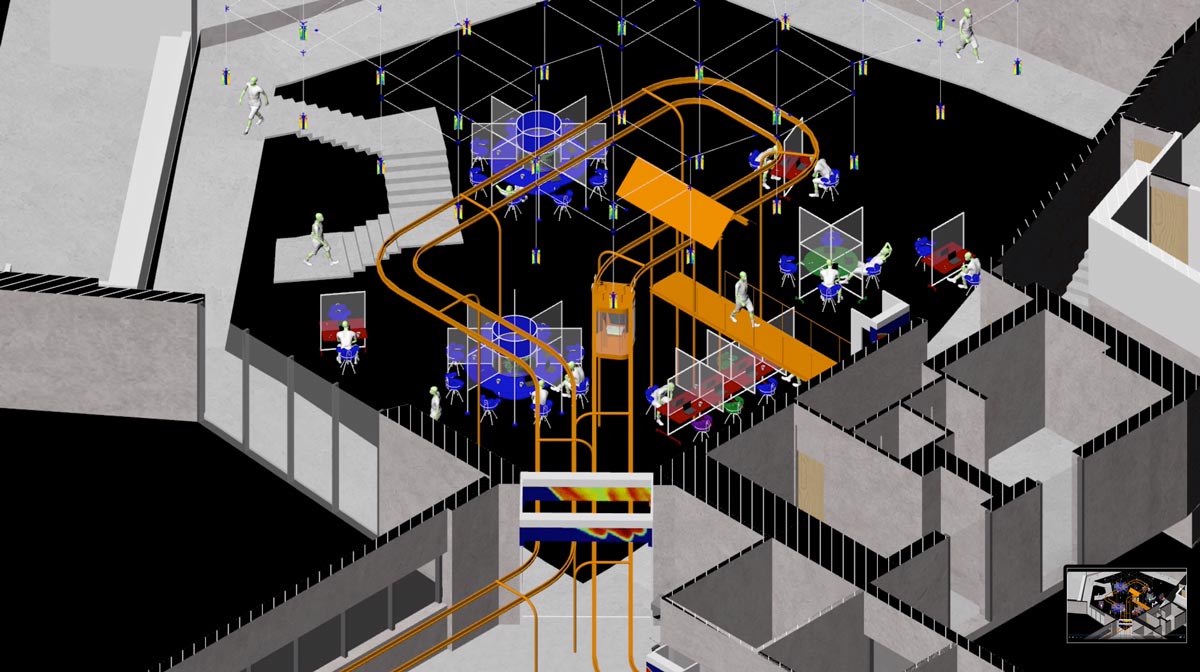

“Back to School,” by Adrian DiCorato, Waylon Richmond, Danrui Xiang, and Gary Zhang, took first place in Studio Redux, one of several design competitions that reimagined education in the pandemic and beyond.

During architecture final reviews in April, CMOK hosted the usual mix of faculty, students, and guest reviewers, but it also offered outsiders a glimpse into the review process. Several M.Arch thesis reviews had 60 to 80 attendees listening in — including parents, alumni, and admitted students around the world — while the Thesis Super Jury had 456 unique logins. Other reviews were live streamed via Facebook for an even broader reach.

Cyrus Peñarroyo, an assistant professor and coordinator of the spring 2020 thesis studios, says that even though the online format pushed students to think differently during a stressful time, they rose to the challenge: “Instead of aspiring to the typical pinup, my students took on the challenge of reformatting their work for the screen/the internet by creating websites, videos, and other forms of interactive content that could live on after the review.”

The university’s Office of Tech Transfer is working with Taubman College to develop future partnerships with industry to scale and replicate CMOK for a breadth of institutional and academic applications. Dean Jonathan Massey says that’s an important illustration of how technology can enhance education. The work of the academic innovation team this summer is another. Massey has been an advocate for reforming architecture education since he came to Taubman College in 2018 and says the pandemic has accelerated the need to deliver education in ways that are not only resilient in times of crisis but also lower barriers to entry for a diversity of talented students. He is excited by how the college’s recent innovations can be adapted in the future: “Our goal is to move from emergency remote instruction to resilient teaching, which sustains the imaginative discovery and peer-to-peer exchanges that enrich the design studio but discards the challenges that traditional architecture education poses for many of our students — current and prospective.”

Pal, who has been knee-deep in the work, adds that the advantages of the new digital platforms ensure they will be part of educational delivery even when pandemic-related necessity has passed: “From the momentum I’ve seen in the way things are going, I don’t think we’re ever going to go back to exactly how it used to be.”