A conversation between Beth Gibbons, M.U.P. ’12, social governance and national resilience lead at Farallon Strategies, and Izzy Beshouri, M.U.R.P. ’24.

Gibbons: There’s a huge need for people who understand the natural environment and want to work in the urban setting. It’s a surprising gap where best and promising practices from natural resource management don’t make it into the urban planning and urban design space. I’m excited that you’re going to work on addressing that, Izzy.

I’ve worked in different dimensions of caring for people, social resilience, and designing our social and built environment to support people. I’m currently working as the national resilience and social governance lead for Farallon Strategies. It’s a small team of dynamic, intelligent, motivated people. Thirty-two hours a week is full-time for us, so we’re doing good work with people we like and then putting it down.

Beshouri: Beth, that last point about putting the work down resonated with me. I’ve felt a lot of that through my position with the sustainable food program because we work a lot in food justice, and that can be emotionally exhausting, doing that sort of climate justice work. It’s always a balance of incorporating that personal as well as community resilience.

I was eager to join the front lines of climate adaptation in cities and use the background I had built up through the natural sciences to work across environmental and social systems toward well-rounded climate resilience. That’s what brought me to Taubman College. My undergrad is in environmental studies, and my senior year in that program overlapped with my first year in the urban planning master’s. In the context of the climate crisis, I chose that path because I just feel like there’s no time to waste. With my Taubman degree, I’m focusing on those quantitative dimensions to channel the passion I built up through things like writing a children’s book on piping plovers in undergrad and other soft applications of resilience work. I’m working on finding ways to better channel my influence through GIS or collaborative planning and negotiation classes.

Gibbons: That’s wise. I advise people to use their time in school to get those technical and hard skills because they’re the most marketable. You could learn GIS later, but at Taubman, you have an instructor who will guide you. Learning to use GIS as a tool for community and social resilience takes attention and somebody willing to learn with you and understand your passion. That’s not something you can do in a MOOC, for example. When we want to analyze complex dimensions of our social world, we want to do that with somebody who can help us apply the tools best.

Beshouri: I like the way you define “marketable” because so often people think it stops at the résumé and the job interview. But, once you’re in that position, climate change and related policies are emotionally charged, and it’s hard to depoliticize and bring to communities that don’t want or don’t yet understand it. So to have those tools on hand, like GIS, that can visualize these concepts in a more palatable and legible way really changes the work.

Gibbons: That’s absolutely true. Knowing how to wield environmental planning, design, and policy tools toward the ends you want to accomplish is essential.

We used to talk about doing adaptation by stealth. So it would be like, “We don’t need to talk about climate change, and we can just do adaptation because of sea level rise or something else.” I don’t like doing that. I want to tell people the truth when we’re going to do hard things. But I think there is still an element of accomplishing what you want in your work by stealth. And being able to convey data and visualizations is a large part of how you get there.

At the beginning of our conversation, I mentioned a gap between what natural resource managers and people focused on the environment are doing and upholding as best practices and what’s happening in the urban environment and urban practices. Do you feel like there is a gap, or are you seeing something different as you enter this field?

Beshouri: That was my first suspicion that a gap like that existed. We focus on our limited time in school to build up knowledge and competencies. A lot of people focus on natural science versus social science. Something Taubman College does well, though, is emphasizing being a generalist over a specialist. Many of my peers and I came to school with our passions understood, and many are driven by climate action. Something about U of M that facilitates closing that gap between ecological adaptation and bringing that to cities is that you can take dual degrees. Many people bridge that gap with dual degrees in something like SEAS (School for Environment and Sustainability) and urban planning.

My moonshot idea in high school was to open a landscaping company that fostered nature-based solutions to climate change and facilitated people letting their front lawns grow back into whatever the original ecosystem was. Reintegrating nature into our settlements felt simple yet innovative. Those types of ideas drove me to where I currently am.

Gibbons: So many policy barriers don’t allow people to have native and sustainable landscapes. I’m the chair of the Sustainability Commission for the city of Ypsilanti. We worked for about a year on introducing new ordinance language to stop people from getting ticketed for overgrown lawns, which in some cases are actually native landscapes. The individuals being ticketed had to keep bringing these tickets forward; the council and planning staff got involved. The planning staff is a small team with many other things on their plate, and even small changes, like a lawn ordinance, are difficult. In the end, we weren’t able to change the code enforcing the 10″ limit on grasses, but now residents can submit a request for a native garden so they won’t be ticketed. It’s an imperfect solution but a step in the right direction. Urban planning, for that reason, is an exciting degree because it gives you the tools

to advocate for policies that support sustainable systems, like our neighborhood landscapes. It also gives you a clear view of the way our thinking about cities and what is beautiful and who controls it has changed and continues to change.

Portico: Spring 2023

- Visualizing the Future

- Beth Gibbons, M.U.P. ’12, and Izzy Beshouri, M.U.R.P. ’24, Know There’s No Time to Waste When It Comes to Climate Adaptation

- Vince Hoenigman, M.U.R.P. ’94, Sees the Opportunity in Every Problem

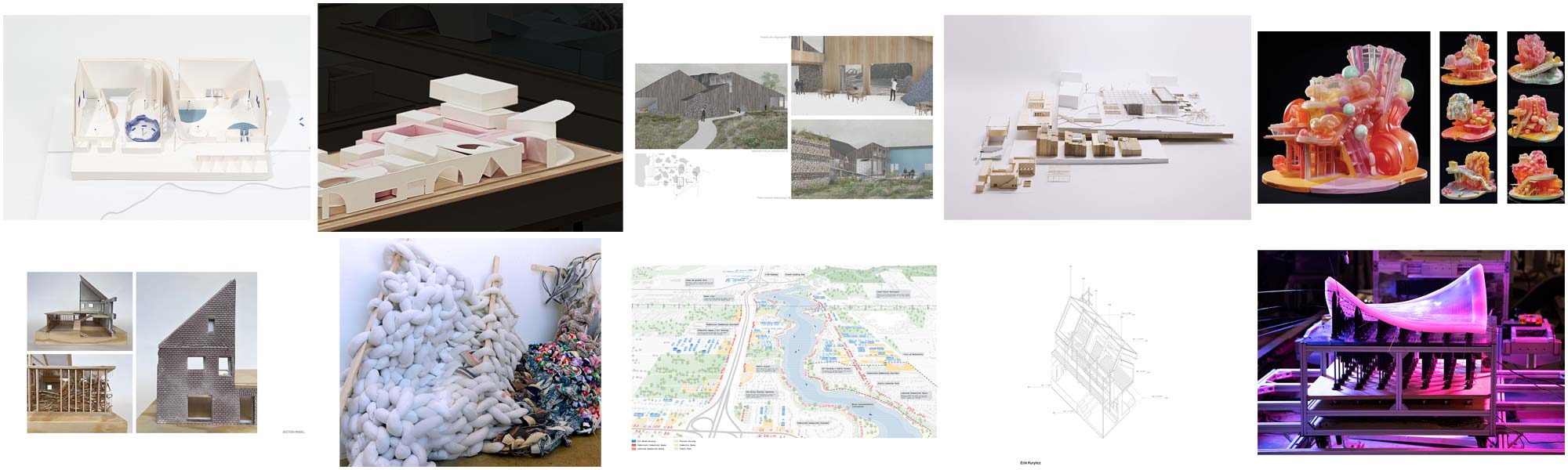

- Architecture Fellowship Program: A Conduit for Innovation Since 1984

- Collective for Equitable Housing Explores Solutions to Growing Affordable Housing Crisis

- Taubman College Students Recognize the Power of Radical Planning

- David Lepo, M.U.P. ’78, Gives Because of the Lasting Impact of His Taubman College Education

- Kristen Padavic, B.S. Arch ’98, Draws Connections

- Help Taubman College Build Tomorrow: Dylan Vaughn-Jansen’s Story