Taubman College is on the leading edge of visualization as faculty and students use interactive tools to democratize design and create space for creative ideas and broader engagement.

Midway down a second-floor corridor of the Art and Architecture Building, room 2106 was once the college library and, more recently, a gallery. But its rebirth this year as the Taubman Visualization Lab — “TVLab” for short — has made 2106 the talk of the college.

Announced by a bright green neon sign hanging just inside a bank of floor-to-ceiling windows, the TVLab has the feel of a hip new storefront — a deliberate choice, says Associate Dean for Academic Initiatives Anya Sirota. Inside is an alluring inventory of digital tools, including virtual reality headsets, 360-degree cameras, motion-capture equipment, a green screen, and a robotic arm. The activity inside is always on display for the curious, who are also welcome to come in and experiment for themselves.

“We wanted it to have a ‘bodega’ feel,” Sirota says. “You know how you can just sort of pop into a bodega and get a candy bar? The idea initially was that you can pop into the TVLab and just casually see what other people are up to. Technology can be intimidating — it can be something that seems like you need years of experience in order to access. So we were very interested in creating a space that would welcome people across the gamut of expertise. And it’s already surpassed all of our expectations in terms of engaging faculty and students.”

The popularity of the TVLab is a testament to an evolution happening not only at Taubman but throughout architecture, urban planning, and urban technology as new technology creates new possibilities for visualization. And as cutting-edge as these tools are, they are also contributing to the democratization of design by letting students, researchers, and practitioners convey designs and concepts in clearer and more engaging ways.

“We’re a school that’s been really, really strong on visualization and representation for a long time,” says Chair of Architecture McLain Clutter. “Our goal is to stay in front of the curve and expose students to technologies that maybe aren’t in the main right now in practice but that we imagine will be really important for them. We may be on the threshold now, but design experts, architects, clients, and all kinds of stakeholders are going to have a more accessible way of communicating their ideas.”

Designing More Functional Spaces

One of 16 courses operating out of the TVLab in Winter 2023 was Assistant Professor of Practice Jonathan Rule’s studio “Augmented Tectonics,” in which students tackled the design and function of healthcare spaces in partnership with a group of students at the School of Nursing. One morning in February, Rule’s architecture students convened to present slide decks detailing their augmented-reality studies of several clinical rooms. On the screen, the paths taken by users through each virtual environment appeared as a series of swooping ribbons that twisted through 3D renderings, revealing the flow of each space — and how busy such rooms can get during ordinary use.

“Augmented Tectonics” students Gabrielle Porter, Richard Hua, and Jirayut Puribhat use immersive virtual reality tools to evaluate the flow of people and activities around a patient in a hospital room.

“Somebody was always bumping into something or someone else,” explained one student, presenting a rendering of a cramped outpatient exam room.

“The monitor is set up so the nurse’s back is always to the patient, which is not ideal,” noted her classmate, about a hospital inpatient room.

Informed by immersive exploration in virtual versions of each space, using wireless headsets and software programs Gravity Sketch, Arkio, and Unity, the students’ studies went far beyond what they might have gleaned from a 2D diagram, or even from the interviews they conducted with nursing students who have firsthand experience in these rooms.

“We’re using this technology because it’s extremely immersive and because it gives us an easier way to communicate with our nursing counterparts,” Rule says, explaining that Arkio allows multi-person group design reviews and that people without access to headsets can also connect through desktop and mobile devices.

That’s especially important given that the nursing class Rule’s students are partnering with is online and asynchronous. This visualization technology will allow them to visit campus virtually, as well as to give the architects feedback on their forthcoming redesigns of the clinic rooms via what Rule calls “playtesting” sessions. That level of feedback is “like a preoccupancy postoccupancy study,” he notes, explaining that this step is not possible with screen- or paper-based designs, or even scale models. As virtual-reality filters from academy into industry, preconstruction playtesting by intended occupants is likely to play an important role in the design process, allowing the people who will live or work in a building to have a greater say in how a building works for them.

Inviting Collaboration and Experimentation

The democratization of architectural design knowledge through visualization is at the heart of Jose Sanchez’s work. An associate professor of architecture, he directs the Plethora Project, a research studio focused on social participation and community cooperation, and designs video games — including the well-reviewed simulators Block’hood and Common’hood — that let non-experts learn about and experiment with architecture and urban planning.

Jose Sanchez’s community building and economy management game Common’hood.

“In architecture, we used to think of physical models or digital models that were static — they were completed and finished and untouchable,” Sanchez says. “But now we have the capacity to create these kinds of experiences that are not just interactive but that can be modeled and shaped in a live experience. And that brings audiences into the work in a different way as well.”

Many laypeople are already primed to inhabit and manipulate virtual environments, either through video-gaming (last year, the market research firm Insider Intelligence estimated that more than 54 percent of Americans were gamers) or simply via the Zoom meetings and digital classrooms that became ubiquitous during the COVID-19 pandemic. And the general population’s growing comfort with digital visualization offers designers new opportunities to communicate ideas, as well as to empower the non-experts who interact with design.

“We’ve started thinking about who has access to the technology; where are the unique voices?” Sanchez says. “The more we open up the field to conversations with audiences from different contexts, I think the questions we use to interrogate architecture are going to change.”

Tony Bedogne, a lecturer in urban and regional planning, has experienced a similar change over two decades of practice as a geographic information system (GIS) developer, most recently for the City of Ann Arbor. “This used to be something where you had to have a supercomputer and a specific lab with a really fancy software set-up,” he says. “Now we’re able to get maps and dashboards right away, using web browsers and mobile applications right on our phones.”

The increasing accessibility of GIS means that planners can call on the community to help make decisions affecting urban life — for instance, the placement of a mid-block crosswalk — in a way that is both more democratic and more responsive to residents’ needs.

“In Ann Arbor, we’ve put citizen engagement mapping in the hands of the public,” Bedogne says. “We can ask people, ‘When you’re out next time walking your dog, mark a place on the map where you might want to cross.’ And then others can like it or comment on it, and we can distill that content and put it up in a visual report, which lets the public understand and weigh in.”

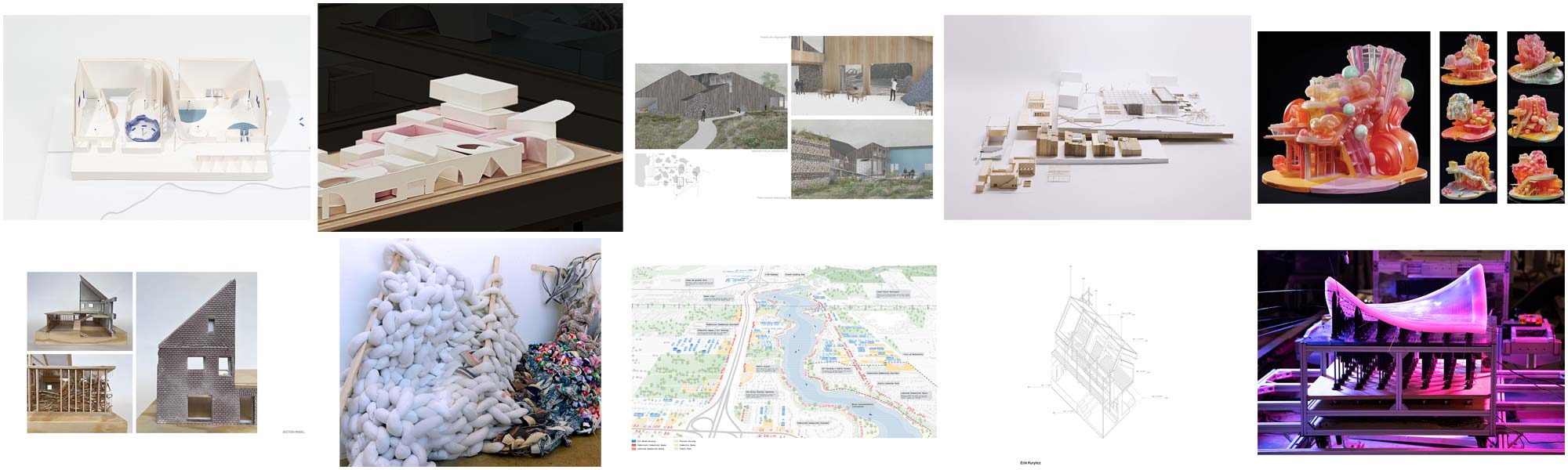

Midterm review of FORM studio projecting

“street view” live streams of students’ site models.

Newly available and richer sources of data can also help planners evaluate how their decisions advance social agendas, perhaps by mapping road improvement work or the availability of city services against socioeconomic data.

“I don’t think we’re there yet, but I hope we’ll begin to consider diversity and equity in new ways,” he says. “I think that could make for better decisions at a local level.” Elisa Ngan, assistant professor of practice in urban technology, is also thinking about how visualization technology can be a tool for equity. It’s a question at the heart of her undergraduate studio, which asks students to collect and visualize data as they consider how everyday urban elements — from lampposts and bus shelters to traffic cones and shop signs — shape the lived experience of a city.

“Visualization as a documentation process is important,” Ngan says, “because what is or is not included in that visualization is what people remember and what gets legitimized. That’s why I teach the students that visualizing things is an act of power — what you decide to keep in or out could be in service of marginalized communities or not, depending on what they see or don’t see.”

While new visualization technology is exciting, it’s important that planners and designers not lose sight of that, she emphasizes: “I feel strongly that visualization is not enough. We can’t just create a visualization and then throw people in there and then expect them to talk about it — it needs to be supported by really sophisticated methods that allow and create space for communities to speak.”

New Possibilities

The power of visualization is more than clear to Taubman’s faculty, but exactly what their students will find when they enter industry remains impossible to predict, given the current pace of technological development. How, for example, will artificial intelligence affect the way we think about design — and designers? What will change as more people enter the metaverse?

“The experience of being an architect is one of just constantly learning new software,” Clutter says. “That’s why we don’t sit students down and take them through software tutorials. What we think is more important is that they learn the practice of constantly updating themselves on new technologies, because the stuff we use now will not be what we’re using five years from now. We want them to learn a way of thinking about technology rather than how they can use a specific technology right now.”

Indeed, the need to adapt to a changing technological landscape may be the only thing this generation of designers and planners can be sure of as they graduate and take their places in industry — but this rapidly evolving visualization technology will also mean the ability to communicate ideas in new and exciting ways.

“In the past, we had more complex, more idiosyncratic representational tools, and a firm’s principle would be tasked with describing their meaning,” Sirota says. “But getting into a virtual space together with a client or community group makes it much easier to discuss project aspirations and the impacts on people, which means it will improve the capacity of designers to interact with stakeholders even earlier in their careers.”

Augmented reality technology is already helping designers connect with clients, but some at Taubman are also experimenting with its potential as a way to connect with other forms of technology — Assistant Professor of Architecture Arash Adel, for example, is exploring how TVLab technology can help designers collaborate with the robots in the Digital Fabrication Lab (FABLab).

Demo by Artists-in-Residence Gibson/Martelli as part of Trade Show.

“I think the most sophisticated and exciting labs are the ones that are agnostic about what is the digital and what is the analog and blend them in compelling ways,” Sirota says. “I think that’s where we’re going to see a lot of invention and innovation in the future.”

Meanwhile, Taubman is also bringing professionals to the TVLab, including the London-based practice Gibson/Martelli, which will be the inaugural participant in the TVLab’s Artist Residency Program. And in March, Taubman faculty held a one-day public symposium, “Trade Show,” focused on emergent visualization technologies. The highly cosmopolitan slate of invited speakers included Indian architect Ayaz Basrai, who uses visualization to create speculative fiction about the future of Mumbai, and Pierre-Christophe Gam, an artist of Chadian and Cameroonian descent who creates immersive installations.

“What I hope will emerge from that is the breadth of radical applications that this technology holds when politics leads the conversation, rather than technological innovation in and of itself,” Sirota says. “As excited as we are about this new technology, with the TVLab we’re really trying to lead with a broader social-political goal — and then seeing what’s necessary to realize it.”

Portico: Spring 2023

- Visualizing the Future

- Beth Gibbons, M.U.P. ’12, and Izzy Beshouri, M.U.R.P. ’24, Know There’s No Time to Waste When It Comes to Climate Adaptation

- Vince Hoenigman, M.U.R.P. ’94, Sees the Opportunity in Every Problem

- Architecture Fellowship Program: A Conduit for Innovation Since 1984

- Collective for Equitable Housing Explores Solutions to Growing Affordable Housing Crisis

- Taubman College Students Recognize the Power of Radical Planning

- David Lepo, M.U.P. ’78, Gives Because of the Lasting Impact of His Taubman College Education

- Kristen Padavic, B.S. Arch ’98, Draws Connections

- Help Taubman College Build Tomorrow: Dylan Vaughn-Jansen’s Story