IN THE NEWS: Sirota's Akoaki Designs a New Future for Detroit’s Oakland Avenue Urban Farm

The following story originally appeared in The Architect’s Newspaper. It features the work of Associate Professor Anya Sirota and her firm, Akoaki, on the Oakland Avenue Urban Farm in Detroit.

Akoaki Designs a New Future for Detroit’s Oakland Avenue Urban Farm

By: Antonio Pacheco

Detroit Cultivator, a six-acre urban plan developed between design firm Akoaki and the Oakland Avenue Urban Farm (OAUF), uses architecture and community organizing to help formalize a legacy urban farm in Detroit’s North End neighborhood.

The OAUF started with a single plot back in 2000, but over time has grown to encompass over 30 lots and 8 structures. Today, the farm administers mentorship programs, hosts classes, and offers community and art spaces alongside its agricultural activities. As Detroit has recovered from financial calamity following the Great Recession, development interests have taken to surrounding areas, threatening the farm’s future.

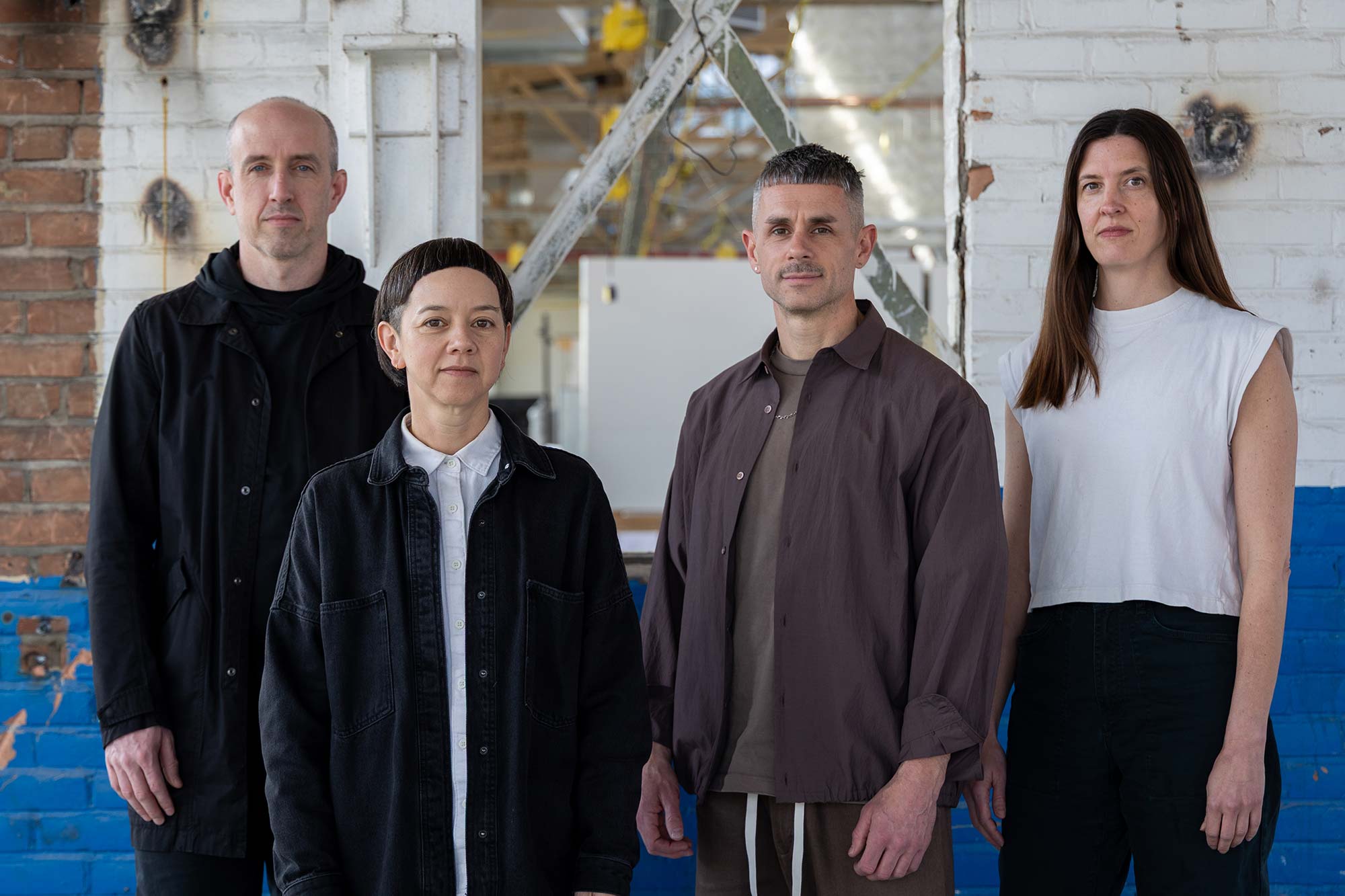

That’s where Detroit-based Akoaki saw an opportunity to apply its design expertise and institutional connections in innovative ways. The firm is helmed by Anya Sirota, associate professor of architecture at the University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, and her partner, designer Jean Louis Farges. Together with neighborhood residents, several university-based teams, and outside “impact investors” like The Kresge Foundation and ArtPlace America, Akoaki has helped design a way to ensure that the farm can become a permanent neighborhood fixture by setting out a long-term growth plan and designing site-based interventions that will promote economic and environmental sustainability.

Sirota said, “As architects, we became interested in the challenge of what architecture could do systemically to create a more sustainable operating system for the farm.”

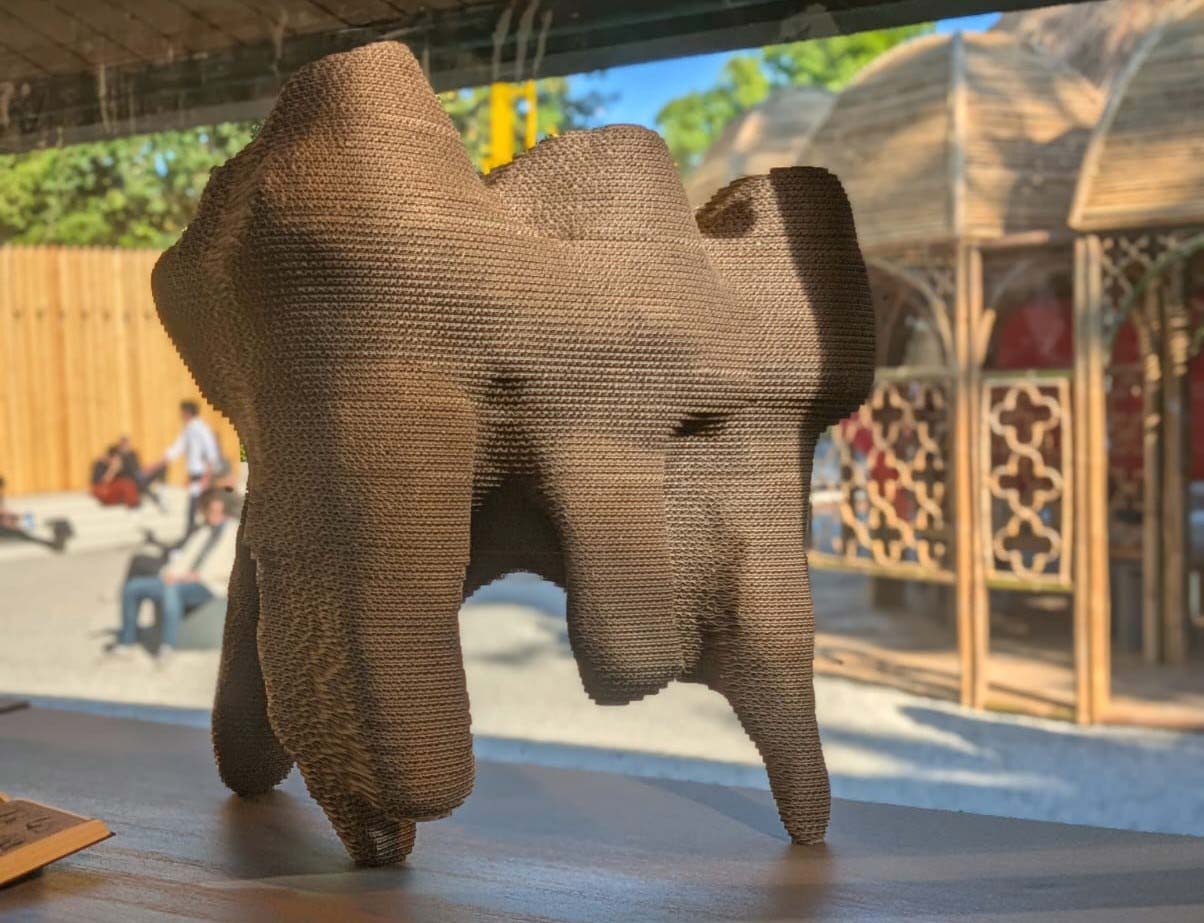

View of a model showing the proposed OAUF urban plan (Jacob Lewkow/Courtesy Oakland Avenue Urban Farm)

The designers sought to discover how the farm could become an “autonomous cultural actor in a complicated urban scenario” that included unclear land ownership, development pressures from land speculators, and water access issues, among other concerns. Because some the farm’s components were located on blighted plots of land that the farm did not own outright, the first step for the project was to secure a path toward formalizing land ownership over these parcels to ensure that developers could not wipe away the farm’s gains. The designers worked with the University of Michigan Law School and a team of “moral investors” to flip the script on land speculators by studying and imitating the tactics they use to exploit Detroit’s land bank. The plan secured land ownership for little-to-no cost via a community land trust ownership model that will keep the land out of the hands of speculators.

Once the existential issue of land ownership had been laid to rest, the team worked with volunteers from the University of Michigan Ross School of Business to craft a business plan for the farm. The plan focuses the team’s efforts on two complementary goals: First, by prioritizing the farm’s productivity to create a stable source of income to fund operations and second, by designing the farm’s individual components to create a flexible one-stop-shop for nascent neighborhood entrepreneurs.

As a result, the farm is peppered with existing structures that will each eventually become activated as public amenities: A vacant big-box grocery store will be converted into a community gathering space containing a commercial kitchen with the help of a for-profit social venture, Fellow Citizen

A site plan showing new water harvesting strategies and buildings (Courtesy Oakland Avenue Urban Farm) In creating their plan, the designers realized that they could not keep the farm purely agricultural, and they instead sought to formalize other existing uses through building and site interventions. The design embraces both the “urban” and “farming” aspects of OAUF, which, according to the architects, is what the community wants and needs most. The project, according to Sirota, represents an “attempt to marry form-making with productive landscapes,” to sustain the social and economic impact of land that was once considered marginal in value. Next, the designers are working on developing and prototyping water harvesting, solar generation, and insulation techniques to help feed into the long-term sustainability plan for the farm while fundraising efforts get underway.