Portico Fall 2020: Lauren Bebry Kenter, M.Arch ’12, M.S. ’13, Helps the Met Design the Future

By Amy Spooner

Like the rest of American society, the art world and museums are facing a moment of reckoning.

It’s a reckoning that predates the events of summer 2020 but has intensified in recent months.

“Returning to work now is more important than ever — to contribute how I can, make changes, learn what my new role is, and help create a more inclusive experience,” says Lauren Bebry Kenter, an exhibition designer at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art whose recent parental leave spanned the continued fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the nationwide protests against police violence toward Black Americans.

Because she helps to create public-facing experiences at one of the world’s most famous museums, Bebry Kenter’s work is high profile. Like other institutions, the Met has grappled with an uncomfortable past. But as it looked ahead to its 2020 sesquicentennial, the Met decided to lean into that discomfort.

Bebry Kenter, M.Arch ’12, M.S. ’13, is part of a team who worked for nearly two years on “Making The Met, 1870 – 2020,” an anniversary exhibition with more than 250 objects organized around 10 seminal moments in the museum’s history. The last gallery, “Broadening Perspectives,” focuses on the museum’s efforts to expand the global reach of its collection and represent cultures and geographics that were previously overlooked.

“This show was conceived to chronicle the evolution of the museum and its ambitions, including examining gaps in its collection and acknowledging steps taken and goals to fill those gaps; for example, curatorial initiatives to better represent women artists, artists of color, and artists from different cultures,” Bebry Kenter says.

In July, the Met’s leadership established a multimillion-dollar fund “to support initiatives, exhibitions, and acquisitions in the area of diverse art histories” as part of a 13-point plan that also includes mandatory training for all staff, hiring a chief diversity officer, increasing diversity in middle and upper management, paying all interns, and drawing nearly all high school interns from Title 1 schools.

As the museum addresses its internal practices and inequities, Bebry Kenter is energized by the opportunity to break traditional patterns: “From a design perspective, it’s exciting to engage with different curatorial intentions and narratives, and to rethink how we can communicate this to our audiences.”

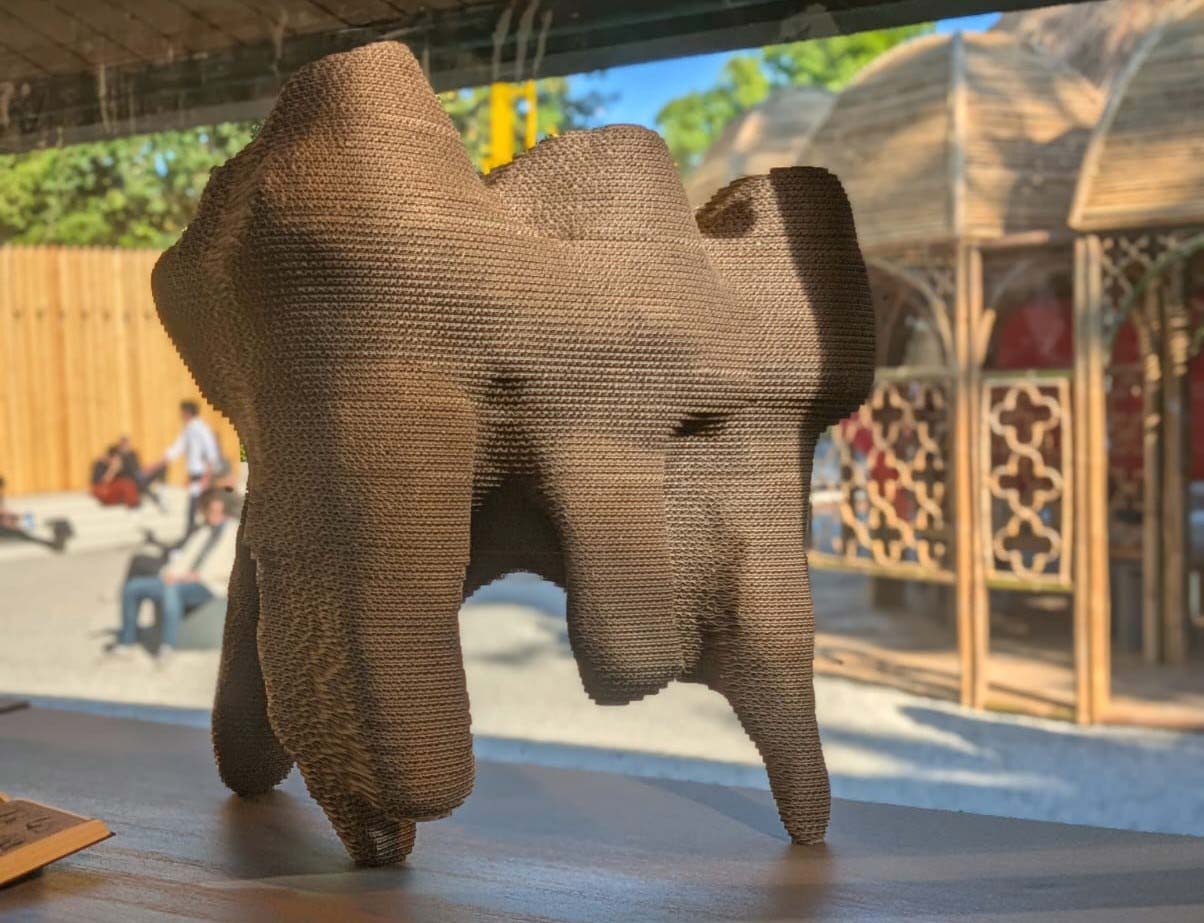

Bebry Kenter calls the work she’s doing now “my dream job,” although she didn’t have a clear dream in mind when she came to Michigan. She had taken a few undergraduate history of architecture courses at Brown University and loved them, subsequently landing a job doing public relations for Skidmore, Owing & Merrill. Being around architects and interpreting their work for a mass audience struck a chord, so she decided to pursue her master’s at Michigan. She stayed on to be part of the inaugural Master of Science in Digital and Material Technologies cohort because she loved digital fabrication. “I’ve always enjoyed being hands on,” Bebry Kenter says. “So a program that focused on making while also being at the forefront of technology was exciting.”

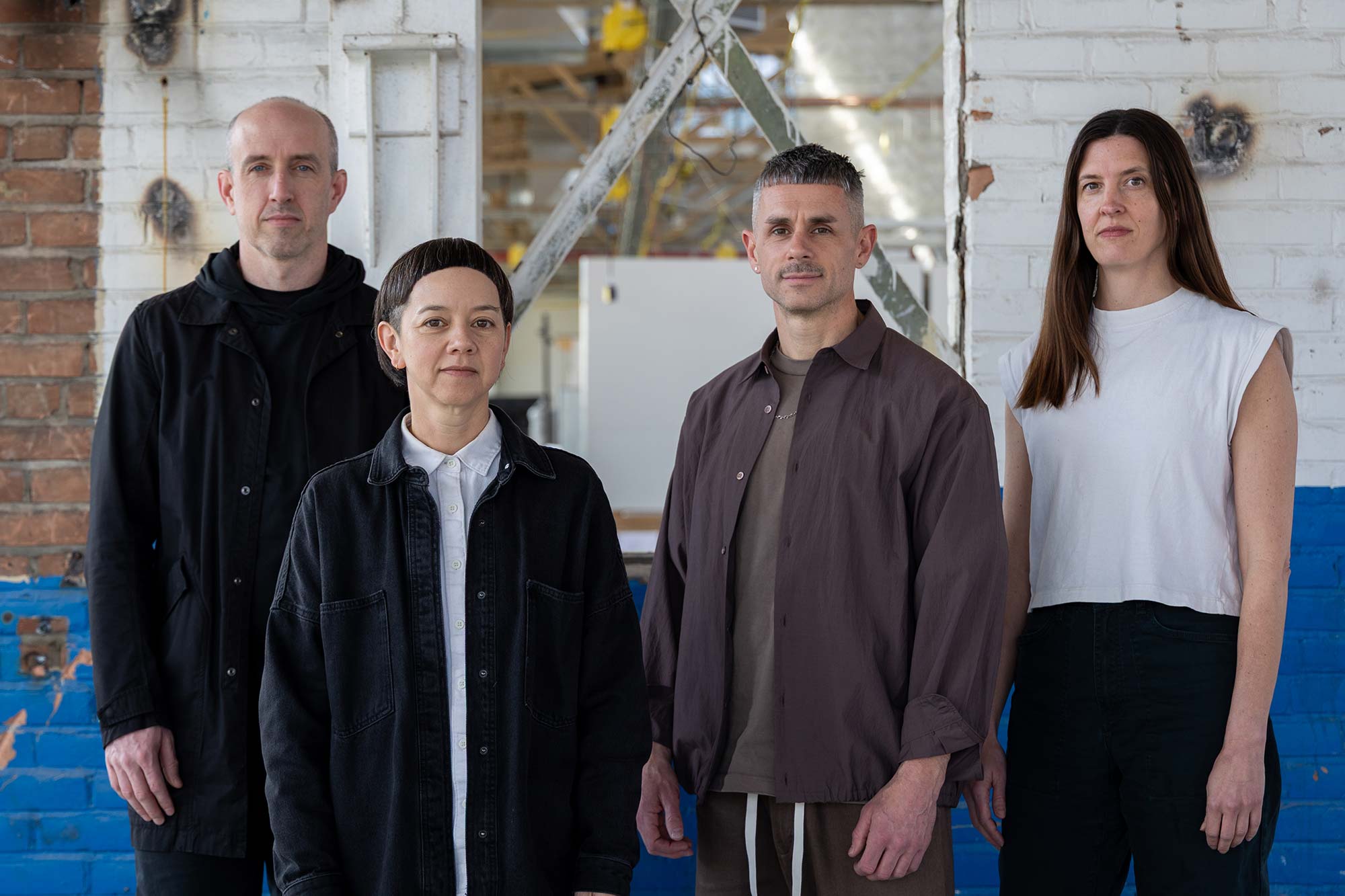

She credits studios and assistantships with Catie Newell and Anya Sirota with helping solidify her plan. “They impacted me a great deal when I was in school,” she says of the associate professors. “I didn’t know what I was doing or how to do it, but both took a chance on me at different times. Through working with them, I figured out what I loved.”

Bebry Kenter’s first exhibition was at the end of Sirota’s spring travel studio in France, a display of the studio’s work at a local gallery. “That’s when I knew I wanted to keep doing exhibitions,” she says, “because it was so much fun and had such an impact on our community.”

As a student, she also worked for then-Dean Mónica Ponce de León on an installation at the University of Michigan Museum of Art; after graduation, she joined Ponce de León’s practice, MPdL Studio. During her five years there, her projects ranged from an installation for a Montana courthouse to one for the 2016 Venice Biennale, among others.

Recalling conversations with exhibit designers in Venice, Bebry Kenter was intrigued when she saw an opening at the Met in 2018, work she calls the flip side of installations: “With installations, I was creating something for a space; now I take other artists’ work and figure out how best to display it so that people can experience it.”

For a medium-size show at the Met, 30 to 50 people work for more than a year to create an experience that will last for a few months. For a large show, it can be more than 150 people. Curators develop a list of items and a story they’d like to tell, and then Bebry Kenter and her fellow exhibition designers use modeling software to configure the space based on the exhibition’s narrative, the artwork, and their display requirements. Some can’t be exposed to air; others have light specifications; optimal display heights vary. The designers also must plot touch-distance requirements to prevent damage to the pieces. They work with art conservators, builders, lighting designers, and security, among many others. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, they also must consider public health.

The work is about designing the physical space — how people will pass through the show and experience the objects on display. It involves a lot of back-and-forth with people who have different perspectives, says Bebry Kenter. “We understand that the way you display artwork demonstrates a contextual hierarchy beyond the object’s physical presence, telling a story,” she says, “and as designers we bring these objects into their physical space. We help make sure visitors can safely pass through the space and learn from, be inspired by, and enjoy the art. The process is incredibly collaborative.”

What first hooked Bebry Kenter on exhibit work at the end of her studio in France still thrills her today: seeing people interact with that which she and her team worked so hard to create — and hopefully learn from and be inspired by it. That’s also the crux of the influence that museums can have amid the tumult of 2020 and beyond, she says: “The best way that people can connect with what they see is to feel like they are a part of it, that it speaks to their history or culture. Having new types of things on display will help feel connected — and our cultures will be celebrated in different ways.”