Vanky: Using Data to Make Communities Equitable and Enjoyable

Digital data and pervasive sensing technologies are optimizing traffic management, infrastructure monitoring, and security. But Anthony Vanky and other designers and planners working in the field of urban technology know those technologies can do more.

Vanky says data can make cities healthier, more equitable, and more resonant with people — even more fun.

“Through ‘data exhaust’ — the digital smog of our data world — we can measure the effect of planning decisions in new ways,” Vanky says. “For example, cities have never really thought about whether people are enjoying the public space.”

Vanky, an assistant professor of urban and regional planning, also is co-founder of Social Studies, a consulting and research and analytics firm that guides governments, businesses, and nonprofits on these topics. One of his collaborators was the City of New York Planning Department, just after it completed a new flagship park. During the planning process, the city had held community meetings where residents said they didn’t need basketball courts, they wanted tennis courts.

“That was a red flag,” Vanky says. “The city was worried it was coded language for ‘we don’t want minority residents here who would probably use basketball courts more than tennis courts.’”

Following the traditional planning process, the city didn’t have means to push back because that’s what the community said it wanted. So they put in one basketball court and many tennis courts. “But the question that we can examine with digital data is who is using these parks,” Vanky says. “Did a traditional community planning process create a less-equitable space that excluded a population?”

The answer comes from digital data “exhaust,” the byproducts of cell phone data or mobile apps, which offers an understanding of the movements of people through space. From there, Vanky’s research seeks to move toward a paradigm of seeing whether people are enjoying a space and how they are using it.

“Then we can begin to test theories and processes that have been traditional to planning and urban design and really rethink them,” says Vanky.

The increased quantity and quality of data offers wide-reaching benefits to cities of all sizes.

As one example, public health officials have relied on annual hospital data of overdoses to identify areas hard-hit by opioid addiction. That presents an incomplete picture because of the lag in data and the fact that all addicts don’t require hospitalization. Vanky mentored a startup that developed a way to perform high-frequency, neighborhood-level epidemiology by placing sensors in sewers to measure the collective microbiome in human waste.

“This platform bridges big urban cities and small rural ones because opioids are everywhere,” Vanky says. “Now we can focus treatment with greater precision, instead of spending more money in places where there are more people, which leaves smaller-but-hard-hit cities behind.”

As data becomes more sophisticated and sensors become more prevalent, privacy concerns are growing. Vanky acknowledges, “We have to balance privacy and innovation.”

He points to Project Green Light in Detroit, a partnership between the Detroit Police Department and private businesses that installed real-time camera connections with police headquarters. The city touted the project as “blending a mix of real-time crime-fighting and community policing.”

But its use of facial recognition technology, like LinkNYC, “has many question marks,” Vanky says. “Because it’s under the umbrella of public safety, police and private companies may keep the data indefinitely, and there is a lot of opacity surrounding its use, including the inherent biases in the algorithms that make this surveillance useful for the police. That should give us pause.”

People willingly share their data all the time — clicking “agree to terms and conditions” boxes without hesitation. But they’re trading their privacy for an immediate benefit, like ordering a product or watching dancers on TikTok.

In the urban tech world, “it might take years until someone sees the benefits of improved public safety or traffic,” Vanky says. “That lag is problematic and poses questions around use and governance of urban data.”

Because urban tech is rooted in the places in which we all live, work, and play, Vanky says it presents an unique opportunity for thought leadership: “Part of it is about informing the public about these issues, but the other is about fundamentally rethinking these data regimes and the technology ecosystem to balance these trade-offs. We need to co-create new visions that can re-center the conversation about people.”

An important part of that re-centering, Vanky argues, is to focus on solving problems, not just increasing profits.

He points to innovative ideas that have existed informally in emerging economies for years, and sees opportunities for urbanists to nudge technologists — from big-tech to startups —toward learning from these examples and make a difference in United States.

“Why isn’t DoorDash delivering medicine? Many long-existing services do that in Jakarta,” Vanky says. “Especially in the era of COVID, when travel and distance are issues, why not here? Can we learn from digitally-enabled mutual aid systems in the Global South as we grapple with issues of the pandemic?”

He emphasizes that a core aspect of Taubman College’s urban technology program, and the mindset of the urban and regional planning faculty, is community need: “It’s not about us, the researchers. It’s us as part of a larger community thinking about problems, and solving them together with residents. In this context, it just happens to be solved through the language of technology and computation.”

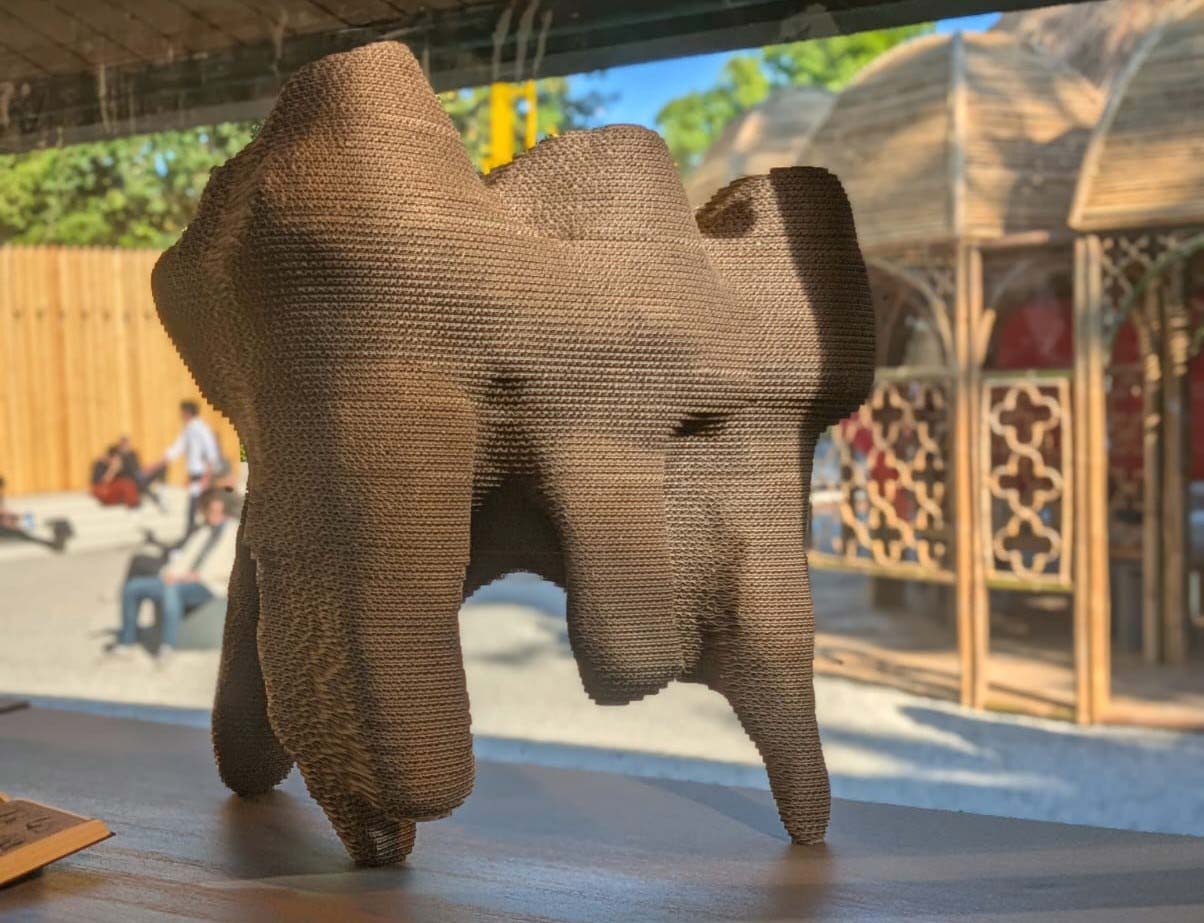

But communities also need to have fun. Vanky sees a role for data in that, too.

What if those basketball courts in that New York City park not only measured who is using the courts but analyzed their style of play, identifying who mimics Kobe and who is more of a LeBron? Even tying the style of a pick-up game to the 1994 “Dream Team” Olympic gold medal game or a legendary NCAA tournament upset?

Beyond the data exhaust and sensors on poles, “by engaging with citizens, we can begin to collect information about cities that promote happier and healthier places, but also create ways for people to connect with each other or look at their space in a new way,” Vanky says. “Sensors don’t have to be only serious; they can support playful engagements that open new types of human-computer-city interfaces that we’re now only beginning to think about.”

—Amy Spooner