Portico Spring 2021 Cover Story: Reality, Untethered

The COVID-19 pandemic sped up the embrace of design technology at schools everywhere. But the revolution was already fully underway at Taubman College

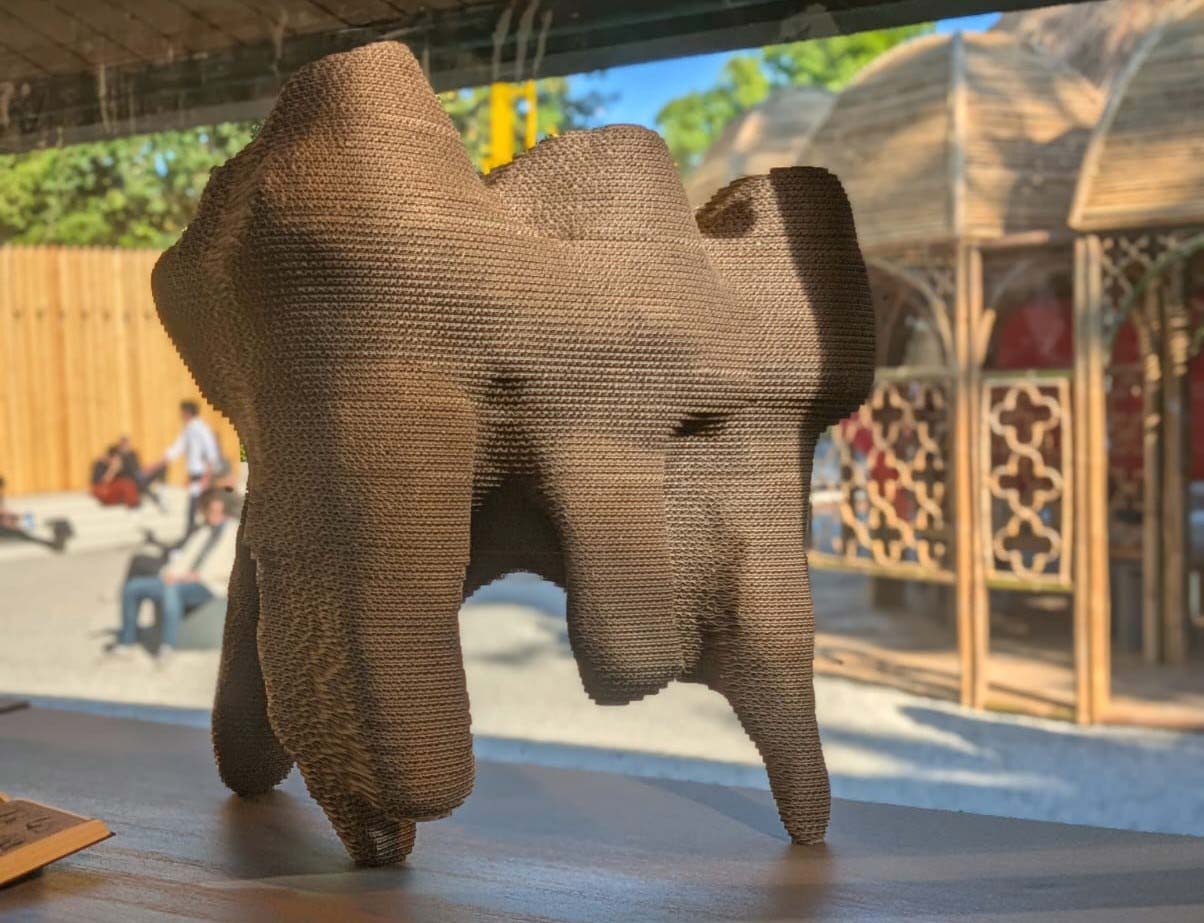

Exploring the portfolio of SPAN, the architectural and design partnership of Associate Professor Matias del Campo and former Assistant Professor Sandra Manninger, is like peering into a future that seems somehow familiar, yet totally alien. Their projects — often beautiful, at times uncanny — range from a 3D-printed porcelain tea set to a “robot garden” currently under construction at Michigan Robotics’ new North Campus building. While many of the forms and patterns appear organic, they’re actually anything but: SPAN specializes in design assisted by artificial intelligence.

“I’m always on the lookout for ways to use computational tools for the production of architecture,” says del Campo. “AI research, as well as other technology like augmented reality, is massively influencing the next steps that we’re making in architecture, both in terms of how we conceive it and design it, but also in the way we put it together.”

“Robot Garden,” design by SPAN (Matias del Campo and Sandra Manninger) and Alexandra Carlson (Michigan Robotics)

Mariana Moreira de Carvalho, M.Arch ’19, worked on her thesis under del Campo, a collaboration with Imman Suleiman, M.Arch ’19, and Hannah Daugherty, M.Arch ’19.

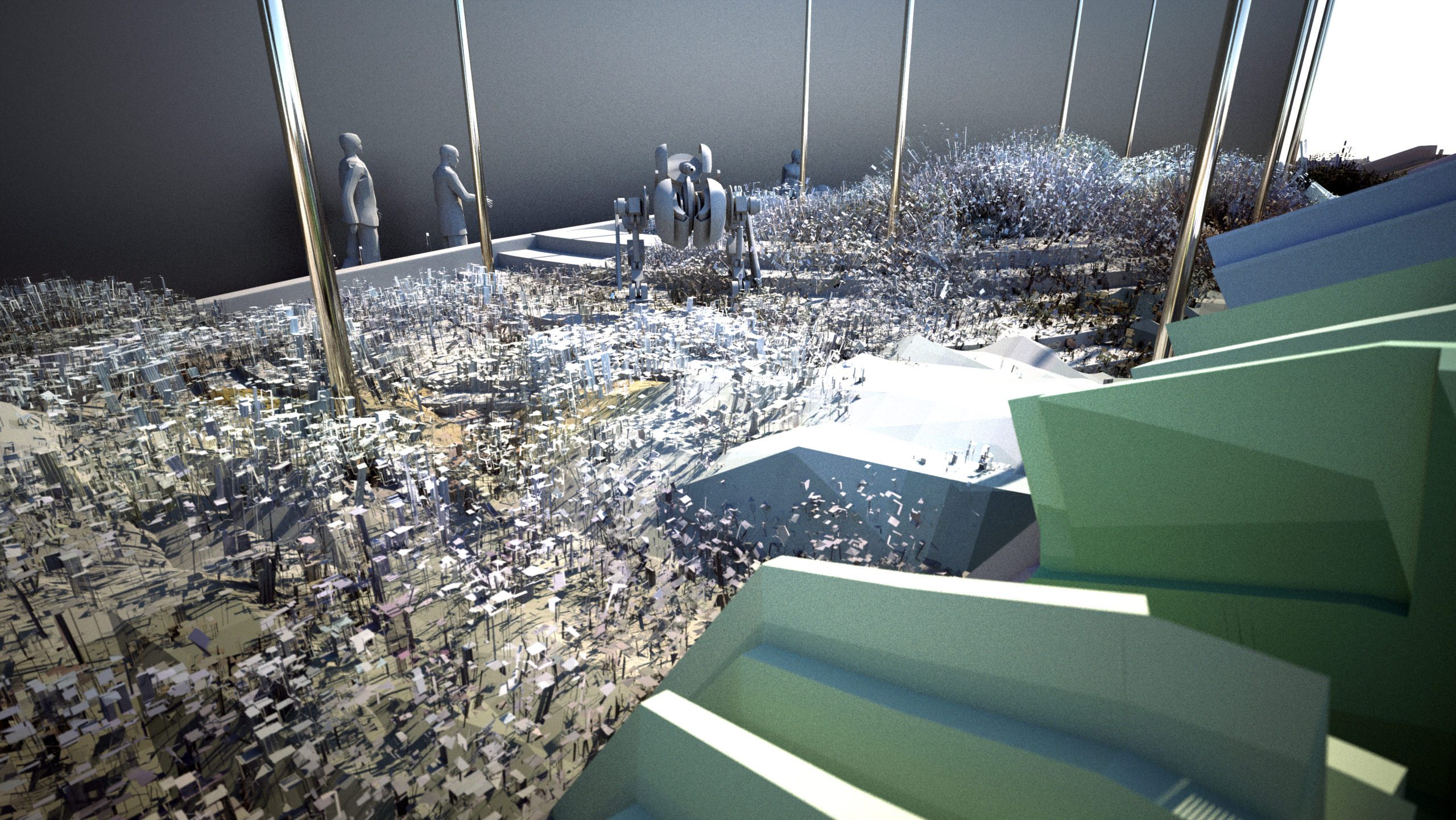

Their project, “Augmented,” (pictured right), involved teaching an artificial neural network — a computing system modeled after a biological brain, which can learn from large datasets — to create an engaging, futuristic spa for a “post-human era.”

Their project, “Augmented,” (pictured right), involved teaching an artificial neural network — a computing system modeled after a biological brain, which can learn from large datasets — to create an engaging, futuristic spa for a “post-human era.”

“Artificial intelligence allows for unimaginable variations,” Carvalho says. “Using the computer as an active partner expands the architect’s imagination and creativity.”

As excited as many architects are about AI, it’s only one among a suite of digital design technologies that are revolutionizing both practice and teaching, from academic work at the cutting edge of theory, to the design and construction of traditional office towers. Extended, augmented, and virtual reality, or XR, AR, and VR, are helping architects, clients, and students explore spaces in new ways. Meanwhile, ever more sophisticated building information modeling (BIM) has simplified the planning, design, construction, and management of infrastructure projects, while furthering sustainability goals.

“These technologies [are] addressing questions around assembly, efficiency, innovation in building science, and quantitative performance,” says Anya Sirota, the associate dean for academic initiatives, who is leading the college’s effort to expand the boundaries of design technologies in education. “On the opposite end of the spectrum, the same methods have untethered us from the normative constraints of reality, pushing the envelope on what is possible to achieve in real space.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has sped up the embrace of design technology at schools and universities everywhere, as teaching moved to an online format. But the revolution was already fully underway at Taubman College, especially among the faculty who make up the Computational Design and Material Systems Innovation Cluster. Through their research and teaching, they are exploring the possibilities of neural networks, digital formwork, and robotic manufacturing. Their students are taking full advantage of the college’s state-of-the-art Digital Fabrication Lab (FABLab), which boasts six industrial robots, large-scale CNC machines, and other digital manufacturing tools. They are forming partnerships across the University of Michigan, including with Michigan Robotics, Computer Science and Engineering, and the Center for Sustainable Systems. And they are helping the next generation of architects and researchers to think differently about how we construct and inhabit the built environment.

“Faculty and students are redefining the way architects represent spatial conditions and communicate ideas, offering antidotes to disciplinary orthodoxies,” Sirota says. “What’s exciting, too, is that these tools invite students to design entire environments, including the atmosphere, the choreography of experience, and the avatars that inhabit them … [and] imagine empathetic ways in which architecture can communicate and shape culture.”

A generational shift

Much of the groundwork for Taubman College’s involvement in design technologies was laid by Professor James Turner, B.S. ’71, M.Arch ’73, who died in January. A member of the faculty from 1976 until his retirement in 2009, Turner developed early versions of programs that today’s architects and architecture students rely on, especially one that was a precursor to BIM. He also created or revised courses on CAD fundamentals and computer programming, including in 2D and 3D computer-aided design.

“From 1970 to 1982, there were few 2D drafting programs and no 3D modeling, visualization, or animation programs, so we wrote our own and made them available to students,” Turner recalled in a 2009 Portico essay.

By the time Turner retired, a host of commercial software applications had become ubiquitous at what is now Taubman College, and faculty and students no longer needed to build them from scratch. Meanwhile, design technology filtered into the mainstream, as even the most established firms have recognized the possibilities for making processes more efficient and unleashing the designer’s imagination.

“I’ve been saying this for probably 15 years now, but I think we’re in a generational shift,” says John Haymaker, B.S. ’90, a former student of Turner and director of research at the global firm Perkins & Will. “Some of the older designers are more comfortable starting with the fat pen first and understanding the big design moves from an intuitive and experiential perspective, and then they’re applying technology a little later in the process. But I think there’s a new generation of designers who are very comfortable sketching with the computer, doing design exploration right away using design technologies.”

With 25 studios around the world, Perkins & Will is continuously exploring the possibilities of design technologies, including through relationships with universities. Another vehicle for generating exploration is Innovation Incubator, a firmwide program that distributes micro-grants to employees who apply to investigate ideas of their choosing — including new technology, tools, and processes.

“It’s a bottom-up effort to make sure that we have our ear to the ground,” Haymaker says. “And we balance it with a top-down approach as well, with our research labs, which do longer term, more focused investigations to develop new tools and fold them into our work processes. What we’re really focused on is understanding the gaps or challenges in delivering built environments that are more sustainable, healthier, and more experiential — and identifying how to do that efficiently and economically. As we learn, we translate that research into practice.”

Firms are finding that technology has a place at nearly every level, from conceiving a project to managing construction and even trouble-shooting a completed building.

“I think that the biggest way design technologies are changing architectural practice is related to communication,” says Andrea Springer, M.S. ’13, the Denver-based director of digital technology and innovation at Stantec, an international design and consulting company. Virtual reality, BIM, and XR now allow cross-disciplinary teams to collaborate remotely, as well as facilitate communication with clients. Stantec’s project teams have the ability to ask a facilities management team member to wear a camera-equipped, augmented-reality headset while walking around a building site, for example, which allows everyone to see the site in real time and communicate seamlessly from wherever they happen to be.

Taubman College graduates, Springer adds, “are in high demand” in the job market because they arrive having already used a variety of digital fabrication methods and design technologies as part of their education, and having been exposed to professors whose research is furthering the possibilities of these tools. “That background is part of the reason why I’ve been able to successfully chart a nontraditional architectural career path, with a focus on technology and innovation,” Springer says.

Akshay Srivastava, M.Arch ’19, a technical designer at the Chicago-based firm Solomon Cordwell Buenz, says that while much of the design technology he relies on at work is fairly new, it has quickly become ubiquitous. Grasshopper, a visual programming language for a computer-aided design platform called Rhinoceros 3D, is “like using a calculator for designing,” he explains. “We use it to understand the form of the building, or set floor plans, or understand the area of a place, just to make our calculations a little quicker.”

Srivastava earned his undergraduate degree in India, where he says architectural education is “very practice-driven — whatever I was studying in school had to be applicable in the real world.” He considers his Taubman College education more theory-based, which provided him with a valuable balance. “At Taubman, it was more about thinking out of the box, and it was important for me to explore more and delve more into the philosophical side of design.”

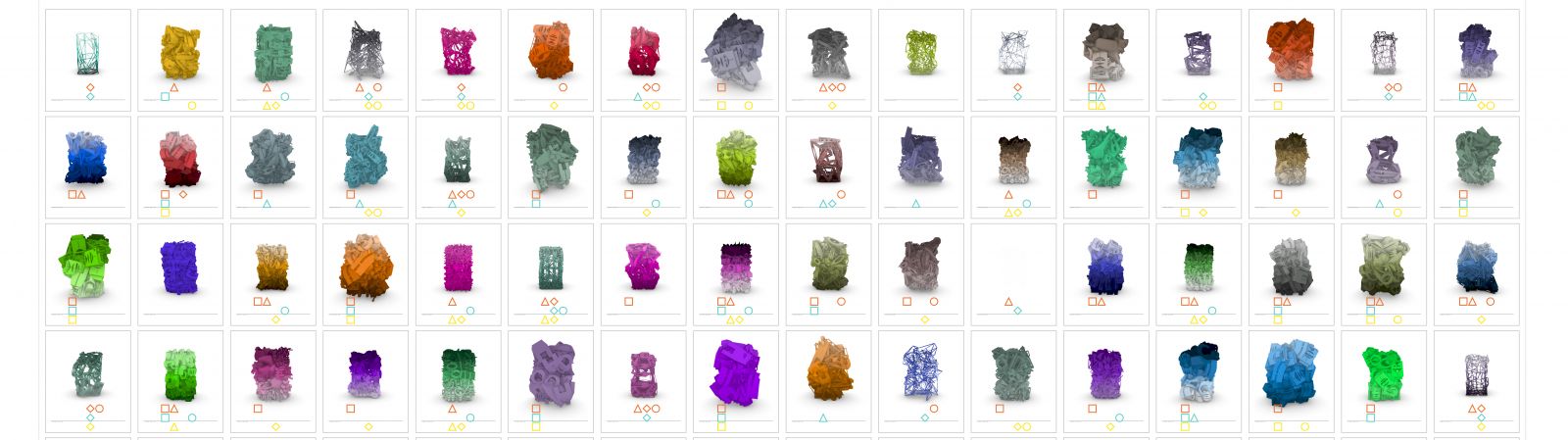

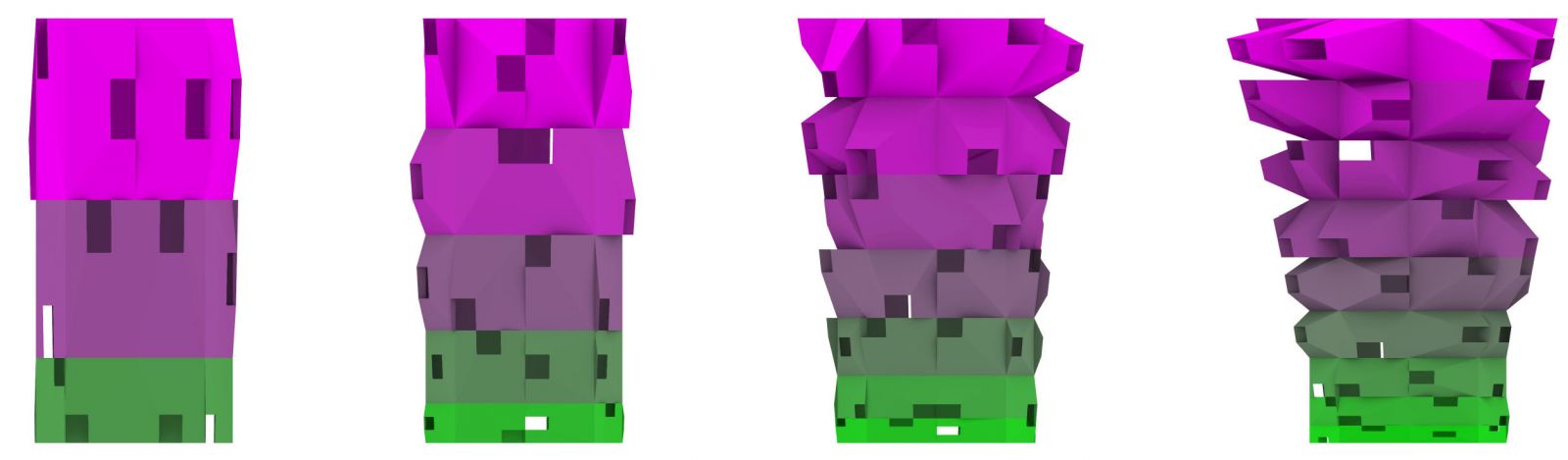

This series of complex, user-driven 3D architectural configurations, co-designed by Akshay Srivastava as a student, demonstrates what machine learning and AI can generate.

Dillon Erb, M.Arch ’14 and Daniel Kobran, M.Arch ’14, who cofounded the cloud-computing startup Paperspace, were also drawn to Taubman because of its investments in the technology side of design. The pair realized while still at Taubman that the cloud had the potential to broaden access to design technologies, which require more computing power than many people around the world have. “There’s a whole lot of good engineering and technology, but it’s really hard to access,” explains Erb, whose work with Kobran is profiled in more detail on page 32. “We realized that it was a design problem just as much as anything else, so we were like, ‘Cool. We can do work here.’”

In 2020, as universities took education online, Taubman contracted with Paperspace to help far-flung students access the college’s technology remotely. The partnership was part of a broader effort to ensure continuity and connection through the pandemic — and that has revealed the importance of incorporating technology into classes even after in-person learning resumes.

Technology for the post-COVID classroom

This year, Matias del Campo was one of three Taubman faculty, along with Arash Adel and Laida Aguirre, to win a grant from U-M’s Center for Academic Innovation XR Initiative Fund. His project, called “Fully 3D,” aims to take remote education beyond the two dimensions of the laptop screen. “I’m trying to figure out a way to use a more three-dimensional approach for sharing information, especially if we’re talking about architecture, which is such a profoundly three-dimensional discipline,” he says.

As evidenced by the robot garden and other projects, even before the pandemic del Campo was already interested in the possibilities of extended and augmented reality, tools that overlay real-life images with additional layers of information, from text labels to ornamentation and special effects. “If we’re assembling a more complex figure or object, for example,” he says, “we can use augmented reality to show somebody where the specific elements go and how they’re assembled literally in space, instead of on a plan or a drawing.”

VR, XR, and AR often require high-tech hardware; in the classroom, del Campo has had students use a headset called the HoloLens to help them assemble their designs out of physical materials. The pandemic, however, highlighted the need to create a system that students could use with more readily available technology, such as their smartphones and Rhinoceros, a design software platform that every Taubman student now learns to use. “It’s important to me that students actually focus on the problem at hand,” he says, “rather than having to solve the technical issues that come along with it.”

Jonathan Rule, an assistant professor of practice, received an XR Initiative Fund grant last year for a pilot project to incorporate VR and AR into his construction classes — with virtual visits to buildings and construction sites and an app that allows students to interact with 3D models as they create designs. Before campus shut down, some were able to use a virtual reality headset called Oculus Rift, an experience that Rule says helped them understand construction methods and materials far better than a textbook alone. “The ability to walk through a virtual space and understand it is very similar to how you can walk through an actual space,” he says. “When you’re seeing things on the page of a textbook, you don’t have a relationship with scale, you don’t understand how big something might actually be. But if you can get inside it, you’re immersed in this world with the freedom to look around.”

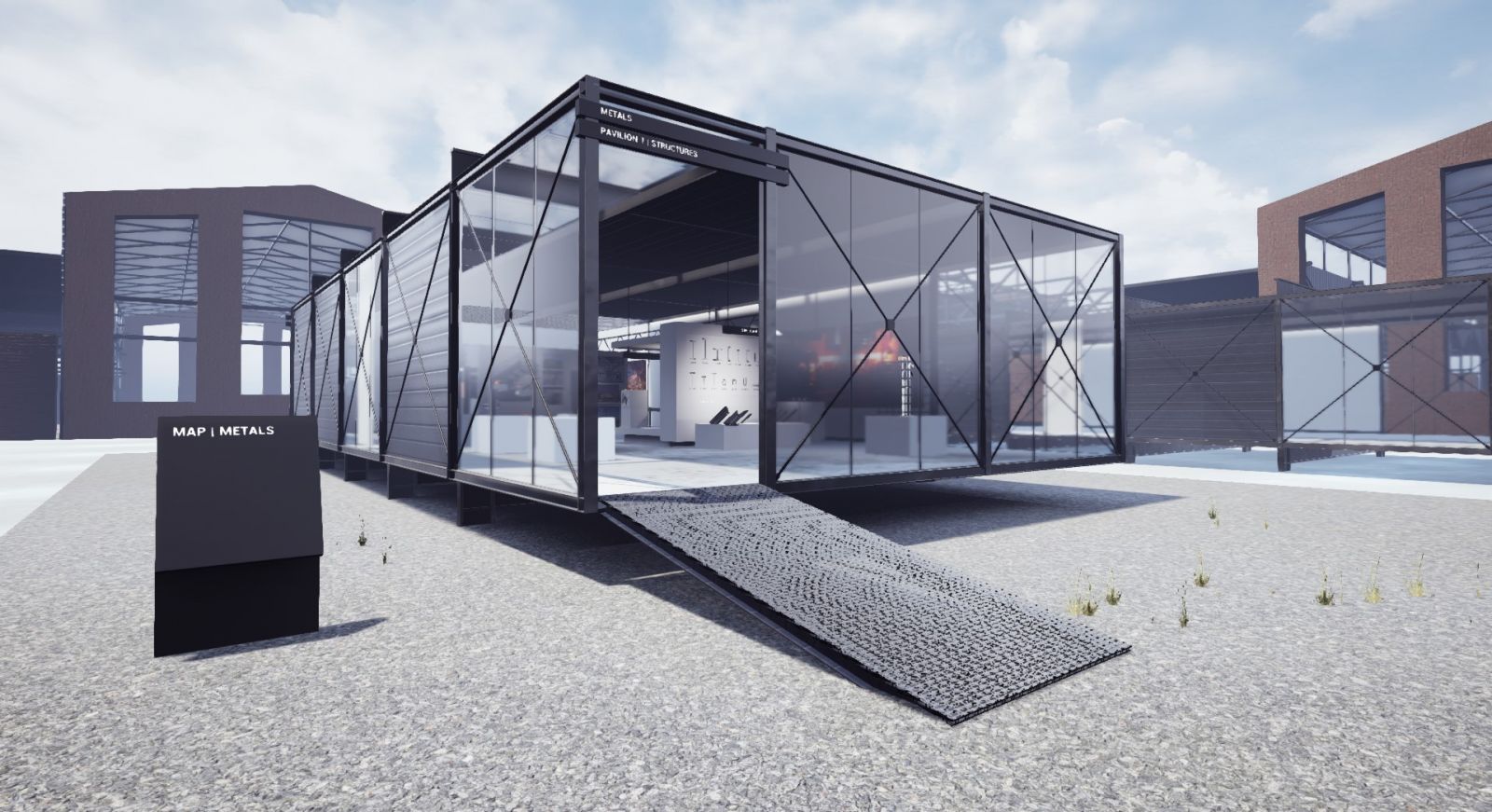

Students in Jonathan Rule’s class visit buildings and construction sites through VR- and AR-powered technology.

Rule notes that VR hardware is not always accessible to everyone — some people can’t use it because it makes them nauseated, while remote students don’t always have access to school-owned hardware.

So Rule also provided his students with a first-person controlled desktop app to download onto their own devices. Everything is still in the testing phase, he says, but he hopes to fully implement the technology in his classes for fall 2021.

Last spring, when the pandemic forced all courses to transition to virtual, Glenn Wilcox, an associate professor of architecture, was already developing a fully online course on design computing with the programming language Python. The course would make coding more accessible to a broader range of students — something that is a pressing necessity as the industry comes to depend on architects who are also skilled programmers.

Wilcox, whose father was an engineer, had been interested in coding from a young age, and he began teaching it at Taubman a decade ago so students would be able to work with the college’s digital fabrication technologies. “When digital fabrication became more prominent and available, I realized that the way to really access the power of it was through a higher-level computation,” Wilcox says. “I always see computational stuff through a lens of what we can actually build with it.”

Glenn Wilcox’s fully online course makes coding more accessible to a broad range of students.

Wilcox is excited by the potential of digital fabrication to move construction beyond standard parts — the traditional brick, for example — and into a world of infinite variations. Digital design and fabrication have made possible stunning contemporary buildings like the Broad Museum in Los Angeles, designed by the firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro and completed in 2015, with its gravity-defying veil that resembles something one might find in a coral reef.

“Modernism produced industries where standardization was the hallmark of production,” Wilcox says. “The ability to vary things is a hallmark of the digital aesthetic.”

New tools for righting old wrongs

Design technologies may have opened new aesthetic horizons, but they also hold potential for advancing other goals, including improving sustainability at every stage.

With the initiation of a new project, teams and clients can now collaborate remotely and share virtual models, rather than flying around the world for in-person meetings. Building information modeling can be used to minimize embodied carbon — the carbon footprint of the materials that go into a structure, which currently makes up 11 percent of global emissions — as well as to maximize the energy efficiency of the building once it’s in use. Digital fabrication allows for more precise use of traditional materials, especially concrete, and it can facilitate the use of greener materials, like mass timber.

“Additive manufacturing (a.k.a. 3D-printing) will be an important element of the future of sustainable building practices,” says Springer, at Stantec, explaining that it will mean far less waste as part of the building process, as well as less need to ship materials to a job site. “It will be a good day when we no longer need large flatbed trucks to deliver large building parts.”

There are also more surprising benefits to design technologies, including, perhaps, the democratization of architecture and urban planning. Associate Professor McLain Clutter, chair of the architecture program, has been exploring how augmented reality might be used to further social justice goals by broadening conversations about urban development.

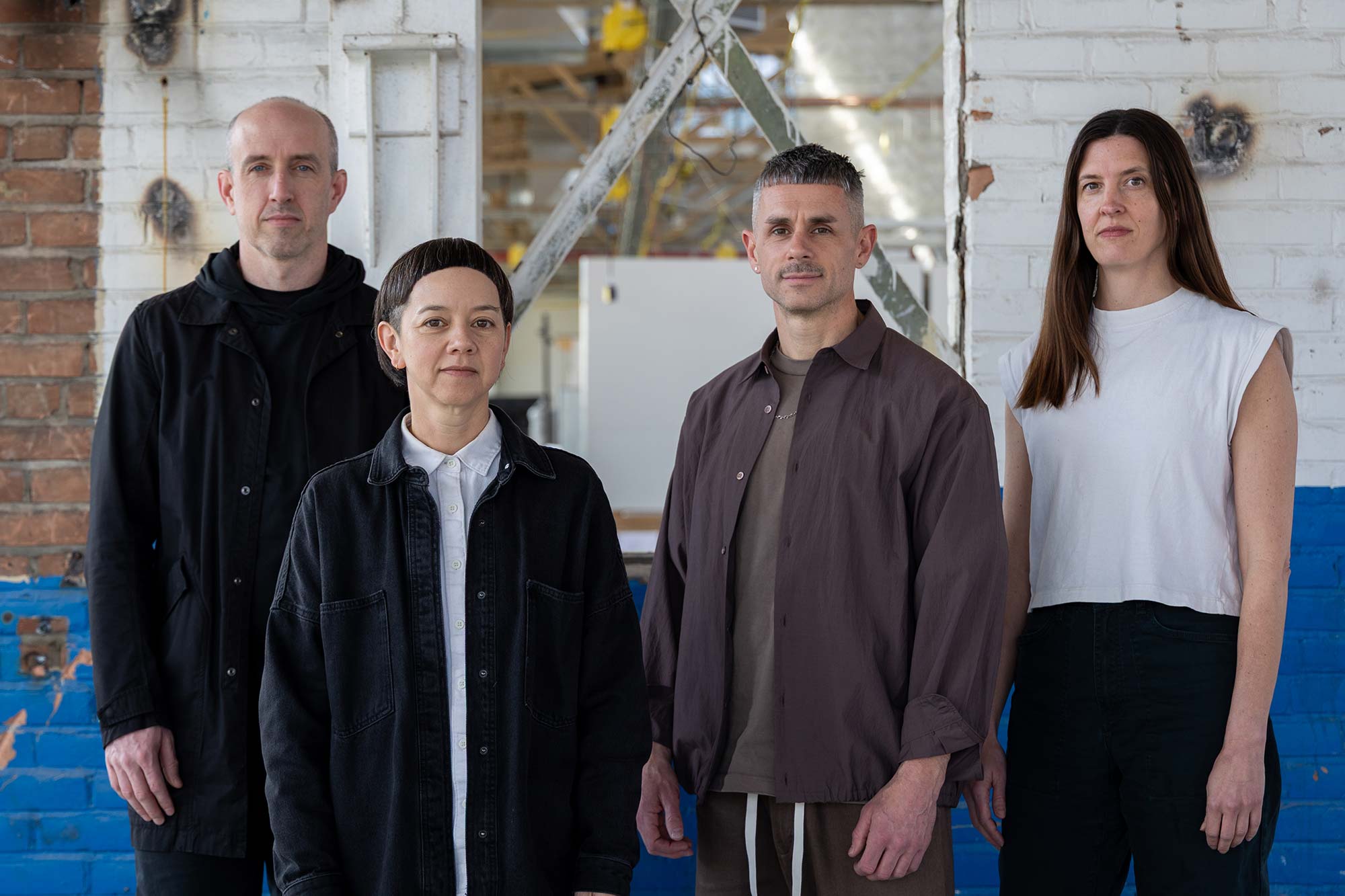

In 2019, Clutter, along with Cyrus Peñarroyo, an assistant professor at Taubman College and Clutter’s partner in the Ann Arbor–based design practice EXTENTS; Assistant Professor of Architecture Laida Aguirre; and Mark Lindquist, assistant professor of landscape architecture at U-M’s School of Environment and Sustainability, created a unique installation in Cleveland’s Slavic Village that aimed to help members of this diverse community take part in a conversation about their neighborhood and its future. “Collective Reality: Image without Ownership” invited local residents into a vacant storefront, where the architects had installed a bare-bones array of foam shapes and steel frames. Participants were then given iPads loaded with an augmented reality app that could overlay virtual images on the shapes.

“We had asked people to go out and to take photographs of elements in the neighborhood that they valued,” Clutter says. “Then we used free software to make digital models, which were available in the storefront space for people to manipulate with augmented reality. We learned a lot about what kinds of interaction were intuitive for people. The things that they valued were relatively unsurprising — markers of green development and new urban vitality. They were also really interested in the kind of unique and quirky parts of their neighborhood, which might push against conventional patterns of development.”

“Collective Reality: Image without Ownership,” by EXTENTS (McLain Clutter and Cyrus Peñarroyo) with Laida Aguirre and Mark Lindquist, invited residents in Cleveland’s Slavic Village to use technology to imagine their neighborhood’s future.

The Cleveland installation, Clutter notes, was merely a prototype — the long-term vision is to make software available to anyone with a smartphone as a way to engage people whose voices are not always included in urban design decisions. Many non-architects already have an intuitive sense of how they can creatively manipulate their environments using augmented reality — think of the popular videogame Pokémon GO, or apps developed by furniture companies to help people shop for the right sofa.

“People might be able to walk past the empty lot or disused park in a community, hold up their phone, and imagine different possibilities of what might go into that,” Clutter says. “They could take a screen grab and send it to their councilmembers. If you give people the tools to imagine how things can be different, you give them agency and they can create their own possibilities.”

Visions of the future

From augmented reality to AI, digital technologies have brought with them a soaring, open-ended sense of possibility. The future they portend may not have arrived everywhere just yet, but for Taubman College alumni who have had the chance to explore distant buildings with VR headsets and realize their designs in the FABLab as part of their education, it can be exciting simply to imagine what else might be next.

After graduation, Carvalho became an associate architect at Hartshorne Plunkard, based in Chicago, where she works on hospitality and residential towers. It’s a bit more practical than the futuristic fantasies she created at Taubman, but she still uses her programming knowledge to help explore ideas and expand her imagination.

“If I want to, I can jump on my computer and train a neural network on an architectural element that I’m into that week — like columns, for example — and get some output images,” she says. “Often what it generates can be disorienting or intriguing, or evocative without being prescriptive. But in the end, it’s just a way of thinking, a way to create fun, intriguing spaces. And there are so many routes, and so many possibilities.”

—Amy Crawford