Portico Fall 2021: Leon Allain, B.Arch ’49, Is Making Others' Paths Easier Through His Scholarship Fund

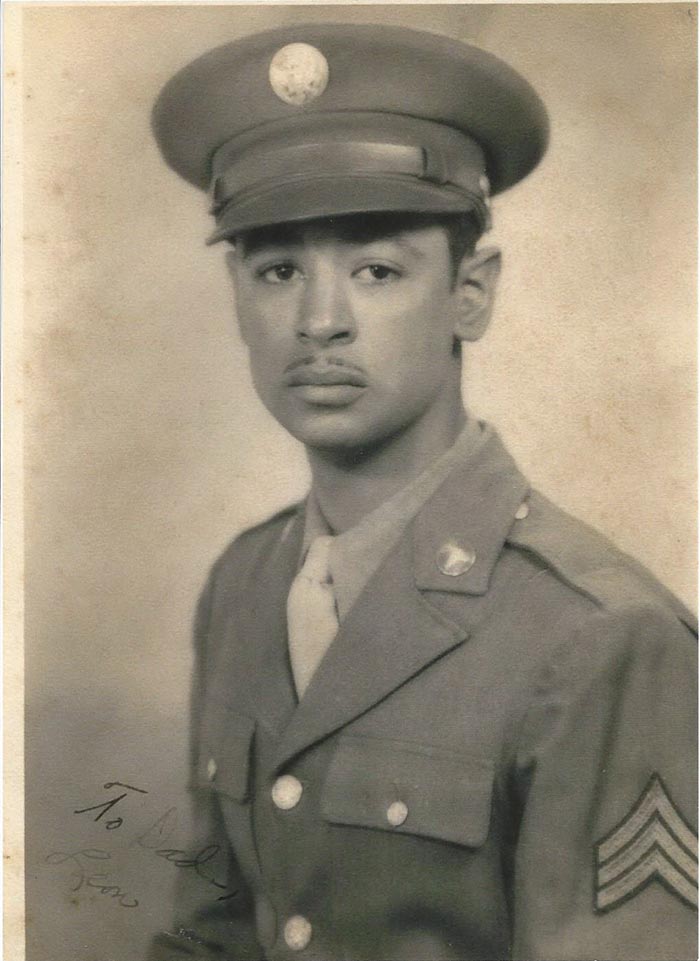

Leon Allain, B.Arch ’49, never really talked about it, but his daughters know that his journey as an architecture student and practitioner — especially early in his career — had to be difficult.

He was one of very few Black students at the University of Michigan at that time. Unable to find work after graduation in his segregated home state of Louisiana, he began practicing in New York City. When he finally returned to the South, to form Miller & Allain Architects in Atlanta, establishing a client base wasn’t easy. Let’s face it: white Southerners who didn’t want to share a drinking fountain with a Black person weren’t clamoring to hire two Black architects.

But Allain persevered, becoming a prominent architect in Atlanta whose portfolio includes the Georgia Dome, two concourses at Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, Morehouse School of Medicine, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Chapel at Morehouse College.

Through the Leon and Gloria Allain Scholarship Fund, Allain is helping to make the journey easier for today’s and tomorrow’s Black architects.

Allain, who died in 2000, and his wife of 48 years, Gloria, who died in 2017, created the endowed scholarship fund when Allain retired and sold his practice in 1999. Recently, their daughter Renee Allain-Stockton and her husband, Dmitri Stockton, completed the pledge payments to fully endow the fund.

Allain, who died in 2000, and his wife of 48 years, Gloria, who died in 2017, created the endowed scholarship fund when Allain retired and sold his practice in 1999. Recently, their daughter Renee Allain-Stockton and her husband, Dmitri Stockton, completed the pledge payments to fully endow the fund.

“Our parents were devout Catholics who upheld the church’s tradition of being of service to others,” says Allain-Stockton. “He never really said this out loud, but I believe that as my dad was selling his firm, he reflected on what got him to where he was and knew that the University of Michigan was instrumental. So he wanted to carry on the idea of giving back and helping others.”

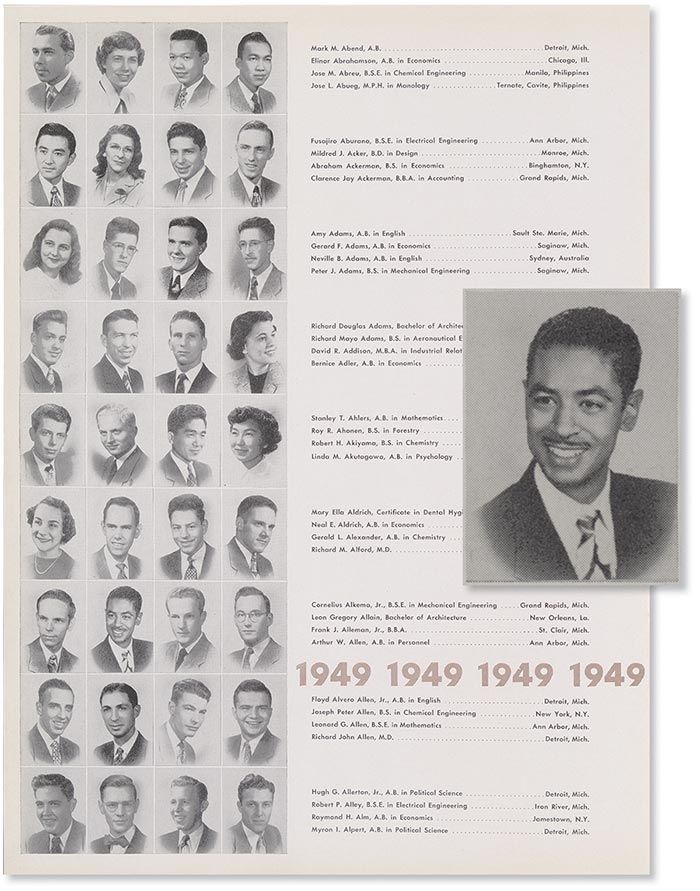

Allain began his college career by enrolling at Tuskegee University at the age of 16. After one year, he transferred to Michigan and then stepped away to serve in World War II before resuming his education.

He first met his eventual business partner, Edward Charles Miller, at Tuskegee, where Miller was on the faculty. Miller went on to become the first licensed African-American architect in Georgia; Allain became the second. They founded Miller & Allain Architects in 1959. Because of segregation, their bread and butter was projects for historically Black colleges and universities. Allain-Stockton recalls attending the first graduation ceremony at the MLK Chapel at Morehouse College: “It was very impressive to see how something that Dad visualized through drawings actually came to life. I’m obviously proud of him and his accomplishments, but what he did in his career is even more amazing when you consider the era he was living and working in.”

Allain founded his own firm in 1967, Allain & Associates. His breakthrough within the Atlanta architecture community came when he partnered with other Black architects in a minority/majority joint venture in the high-profile Georgia Dome and Hartsfield Airport projects, aided by former Mayor Maynard Jackson’s policy that city contracts must have minority representation. Eventually, Allain’s portfolio extended far enough across Georgia that he earned a pilot license in order to travel more quickly between job sites.

It was a way of keeping his family front and center.

“He was always home for dinner,” Allain-Stockton says. “I think he made a conscious decision to grow his practice enough to support us and bring some other architects along, but not to the point where it would command all of his time and attention.”

Now Allain’s daughter and son-in-law are continuing another aspect of his desire to bring other architects along — by finishing the work that he started to create a scholarship fund. “It’s the model of lifting as we climb,” Allain-Stockton says, “planting the seeds for future architects of color to be able to attend the University of Michigan.”

— Amy Spooner