Detroit’s Path to Inclusive Recovery

Working toward a fairer future requires untangling legacies of displacement, segregation, and inequity in Detroit.

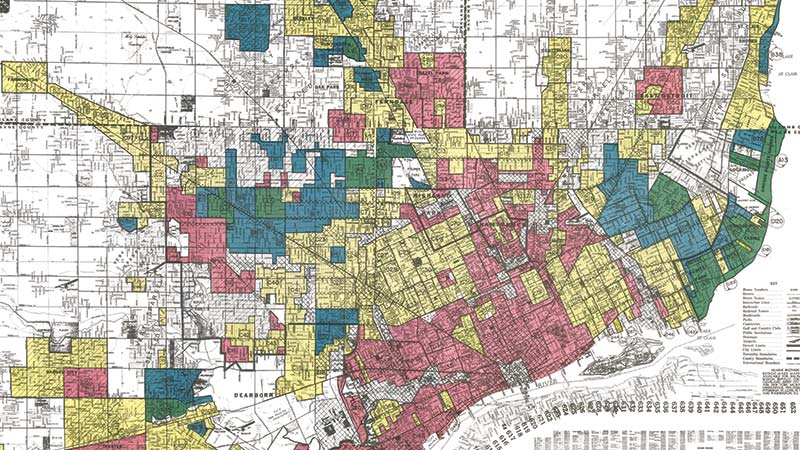

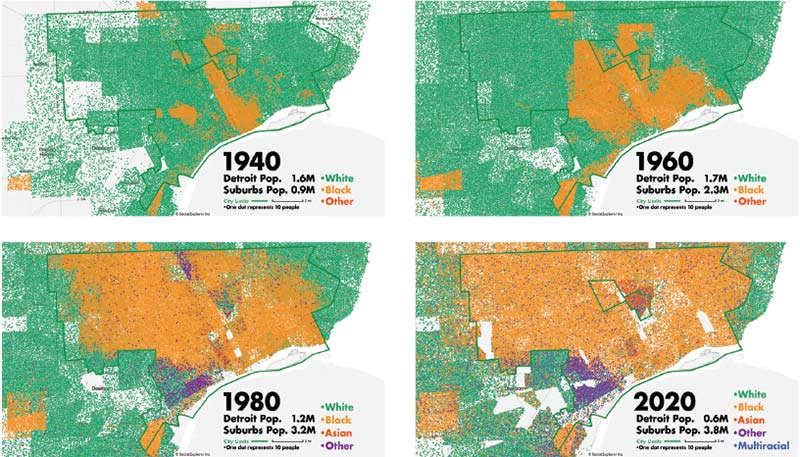

Eight Mile Road marks the border between the city of Detroit and the suburbs of Oakland County. But this multilane thoroughfare, which carries traffic past sprawling shopping plazas and neighborhoods of modest single-family homes built during the prosperous years after World War II, represents more than a geographic boundary. It’s also a stark line between a Black city and its white suburbs, between a community with a median household income that hovers around half the national average and one of the wealthiest counties in the United States.

“When you see it on a map, you start to see how people in Detroit really lost out on building wealth,” says Larissa Larsen, associate professor and chair of Taubman College’s urban and regional planning program.

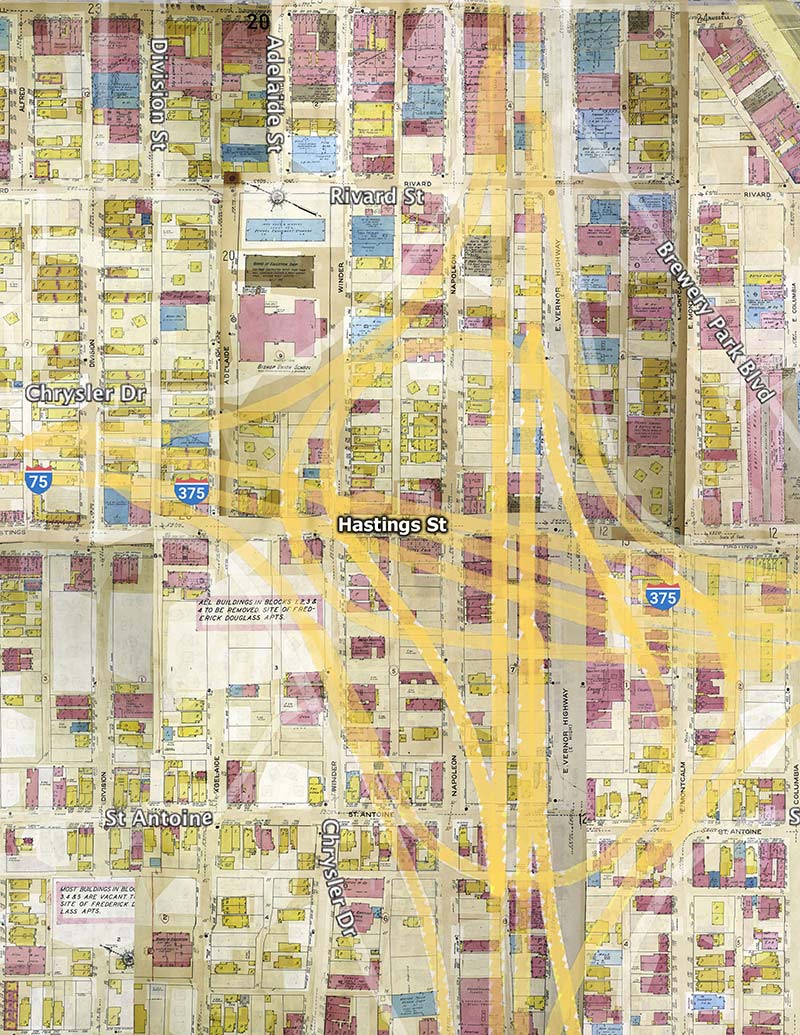

The 1951 Sanborn fire insurance map of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley is georeferenced above the current geography.

Detroit is an extreme example, but nationwide Black families still have about a tenth the wealth, on average, of their white counterparts, primarily because of a gap in rates of home ownership. “Certainly there’s structural racism baked right in there,” Larsen says. “And we, as architects and planners, worked for a century building American cities — so we’ve participated in making that happen.”

History shapes cities in myriad ways: through deliberate planning and government policy, the rise and fall of industries, war, disaster, and migration. The ways in which urban denizens are displaced, segregated, and cut off from resources today are also rooted in the past, and rectifying these inequities requires untangling those legacies. That need is at the heart of an emerging field of research known as urban humanities, which at Taubman College has centered on a grant program called the Michigan-Mellon Project on the Egalitarian Metropolis. First funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in 2013, the Egalitarian Metropolis was led since 2017 by Taubman College’s Robert Fishman, who retired in June as a professor of architecture and urban and regional planning, and by Angela Dillard, the Richard A. Meisler Collegiate Professor of Afroamerican and African Studies and current chair of the history department at the College of Literature, Science and the Arts. Now in its concluding year, the project is evolving into an Urban Humanities Initiative at the University of Michigan, which will continue to connect humanities researchers, planners, and architects, along with community leaders outside the university, as they work toward a fairer future.

History shapes cities in myriad ways: through deliberate planning and government policy, the rise and fall of industries, war, disaster, and migration. The ways in which urban denizens are displaced, segregated, and cut off from resources today are also rooted in the past, and rectifying these inequities requires untangling those legacies. That need is at the heart of an emerging field of research known as urban humanities, which at Taubman College has centered on a grant program called the Michigan-Mellon Project on the Egalitarian Metropolis. First funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in 2013, the Egalitarian Metropolis was led since 2017 by Taubman College’s Robert Fishman, who retired in June as a professor of architecture and urban and regional planning, and by Angela Dillard, the Richard A. Meisler Collegiate Professor of Afroamerican and African Studies and current chair of the history department at the College of Literature, Science and the Arts. Now in its concluding year, the project is evolving into an Urban Humanities Initiative at the University of Michigan, which will continue to connect humanities researchers, planners, and architects, along with community leaders outside the university, as they work toward a fairer future.

Robert Fishman grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, a train ride away from Manhattan, where the strata of history can often be found close to the surface.

“I was one of the bridge-and-tunnel people, as they’re called,” he says with a laugh. “For us, New York was even more of an ideal and a revelation than it was for the people who were actually living within the city — I keep coming back to New York as my archetypal metropolis.” As a teenager in the 1960s, Fishman took frequent trips into the city, spending long hours exploring its renowned art museums. But he also became fascinated by New York itself and by the extremes of wealth and poverty that were often on display. His curiosity led him to The City in History, a now-classic book by the historian Lewis Mumford, first published when Fishman was in high school. Mumford’s lyrical study of how the Western urban form has changed over time — from the ancient Greek city-states and cathedral towns in medieval Europe to the modern capitalist metropolis — would prove a lifelong influence.

“I’ve assigned it in literally every course I’ve ever taught,” Fishman says. “Mumford’s way of looking at the city, his deep understanding of the impact of culture, has certainly shaped my work more than anyone else.”

Fishman went on to study history in college and graduate school, spending the first half of his teaching career in traditional history departments. When he came to the college in 2000, recruited as part of a new master’s program in urban design, he found a student population eager to incorporate historical context into the study of design and planning.

“To be an urban designer, you really have to love the city, which means trying to grasp what is unique about each city,” Fishman explains, “and to understand what is unique about it you really have to look into the past, into the urban biography that has shaped every city.”

Fishman was part of the original team of faculty and students, led by Taubman College Associate Dean Milton Curry, who won the six-year, $1.3 million grant for the Michigan-Mellon Project on the Egalitarian Metropolis. Initially the project compared three cities — Detroit, Rio de Janeiro, and Mexico City — through a framework that assumed the inherent worth and equality of all the people who called each home. What were the most challenging contemporary issues facing these different communities, they asked, and how did their causes and solutions connect to history, economic and political forces, architecture, and urban design? The wide-ranging effort resulted in a series of courses, exhibitions, and symposia, which brought together academics with community leaders from the cities themselves.

In 2019, a second, $1 million grant allowed the project team to take a deeper look at a single city: Detroit, which — more than almost any other in the United States — has seen its fortunes rise and fall on the tide of larger historical forces. After Curry’s departure to be dean of architecture at USC, the project was now jointly headed by Fishman and LSA historian Angela Dillard. Fishman couldn’t imagine the Project without this close collaboration. “I’m something of an outsider to Detroit. Angela grew up as a Black Detroiter, daughter of a prominent clergyman, and someone whose life and scholarship have been deeply engaged with Detroit. She brings a perspective that I couldn’t alone.”

“The Mellon Foundation,” he adds, “had observed that there is an unfortunate separation between schools of architecture and the humanities, and both architecture and humanities could benefit greatly by working more closely together,” Fishman says. “And the other part of the urban humanities concept was the need to include the diverse voices of the city itself, to really engage with the lives of our great cities.”

Detroit was first settled by French colonists in the early 1700s, but the history of the modern city begins in 1910 when Henry Ford opened his Highland Park plant and began churning out Model Ts on the world’s first automotive assembly line. The growing automobile industry drew new populations of workers, including Black Americans, who fled the Jim Crow South as part of what became known as the Great Migration. By 1950, the city’s population was eight times what it had been in 1900, and Detroit was among the most prosperous cities in the world. Overreliance on a single industry proved dangerous, however, and Detroit’s economy and population cratered beginning in the late 20th century as the auto industry decentralized. Due to the legacies of white flight and redlining, the decline hit Black Detroiters especially hard. “Detroit is an interesting case because the highs were high and the lows were so low,” says Larsen. “A 100 years ago, it was Silicon Valley, and the wealth is still there — it just went to the suburbs.”

Detroit was first settled by French colonists in the early 1700s, but the history of the modern city begins in 1910 when Henry Ford opened his Highland Park plant and began churning out Model Ts on the world’s first automotive assembly line. The growing automobile industry drew new populations of workers, including Black Americans, who fled the Jim Crow South as part of what became known as the Great Migration. By 1950, the city’s population was eight times what it had been in 1900, and Detroit was among the most prosperous cities in the world. Overreliance on a single industry proved dangerous, however, and Detroit’s economy and population cratered beginning in the late 20th century as the auto industry decentralized. Due to the legacies of white flight and redlining, the decline hit Black Detroiters especially hard. “Detroit is an interesting case because the highs were high and the lows were so low,” says Larsen. “A 100 years ago, it was Silicon Valley, and the wealth is still there — it just went to the suburbs.”

Larsen, along with Fishman, Dean Jonathan Massey, and Josh Akers, an associate professor of geography and urban and regional studies at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, leads “Racializing Space: Housing and Inequality in Detroit, 1930–2020.” An outgrowth of the Egalitarian Metropolis, the effort involves mapping data from decades of censuses and surveys to show how Detroit’s regional segregation and racial wealth gaps developed.

Mapping plays a role in much of the research currently funded by or related to the Egalitarian Metropolis project. Doctoral student Christine Hwang, for example, is working on a dissertation that focuses on how the Catholic Church, with its parish-based organizational structure, influenced the development of Detroit’s neighborhoods.

“The Catholic parish was much more important in Detroit than in Catholic countries,” Hwang explains, “because it became a place of refuge for Catholics, as well as an ethnically defined space. It was kind of a paradox — the parish was a place of refuge, but only people who spoke Polish or Italian, for example, really felt welcome in the neighborhood that it defined.”

Black Americans, who were mostly Protestant, often sought to enroll their children in parochial schools because they were seen as offering a better chance at upward mobility. Hwang’s next big question is whether those parishes that welcomed Black families acted as an antidote to redlining (the phenomenon in which Black families were confined to the poorest neighborhoods and denied mortgages when they tried to break the “color line”).

Myles Zhang, a Ph.D. candidate in architecture at Taubman College, has also studied religious institutions — specifically, medieval cathedrals. But his more recent research involves less lofty institutions, beginning with the architecture of prisons and extending to places of punishment that lie far beyond their walls.

“It’s looking at carceral spaces that do not at first glance look like carceral spaces,” Zhang says, referring to urban areas that “are spaces of confinement, perhaps through lack of access to resources, like good transportation or job programs, or histories of underinvestment, or stigma associated with those people and places.” Such topics can make a person pessimistic, Zhang admits, but the Egalitarian Metropolis — indeed, the whole urban humanities approach — is concerned not only with the burdens of the past, but with how their lessons can shape the future.

“These historical questions don’t always point themselves toward solutions,” he says, “but they provide an impetus, a motivation, to use the built environment as a tool for social equity.”

Racial dot maps of Detroit, generated by Myles Zhang, show how the city remains racially and spatially segregated. More at racializingspace.org.

The spirit of the Egalitarian Metropolis will continue at Taubman College, notably through the latest iteration of U-M’s Anti-Racism Hiring Initiative, which will fund three new faculty positions in the urban humanities, including one at the college focused on urban design, another in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies in LSA, and a third position that the college will share with LSA’s Digital Studies Institute.

The culmination of the Michigan-Mellon Project, however, takes place next spring, with “The Egalitarian Metropolis: Toward an Inclusive Recovery for Detroit,” a symposium that will bring together U-M researchers and people who are working every day to make Detroit’s recovery equitable and inclusive.

“We need to look to history to understand where to go in the future, how to navigate similar issues, and how to avoid making similar mistakes,” says architectural historian Anna Mascorella, Taubman College’s current Fishman Fellow. “I think it’s critical to understand deeply how our cities came to be where they are today, and to ask ourselves who was — or wasn’t — at the table when these decisions were being made.”

To that end, the conference will be “a project of the urban humanities,” says Mascorella, who is working closely with Fishman to develop it. “It merges the academic disciplines of architecture, urban planning, history, geography, literature, economics, and social work with Detroit community members and civic organizations in order to truly foster critical conversations about Detroit’s future as an egalitarian metropolis.”

The path toward that future may not yet be clear, but Detroit is also not alone in its struggle to be a more inclusive place for humans to live, work, and grow.

“What happened to Detroit is profoundly engaged with deeper global forces,” says Fishman. “It’s these forces, including de-industrialization and changing global division of labor, that lead us to the divided metropolis, to increasing inequality all over the world.”

Global tides shift, however, and the college’s engagement with Detroit has revealed certain advantages — housing, for example, is “naturally affordable” in Detroit, even as other cities experience soaring home prices and rents.

“It was not too long ago when Detroit was seen as a warning about the future for every American city,” Fishman says. “But I think the very difficulties Detroit has faced might lead to better outcomes.”

After all, Detroit’s urban biography is far from complete. And whether the next chapter will be one of egalitarianism or division is up to the next generation of architects, planners, policymakers, activists, and the everyday people who call cities home.

– Amy Crawford