Cool Calculations

Taubman College researchers are developing passive cooling solutions for self-built housing to improve residents’ health and well-being.

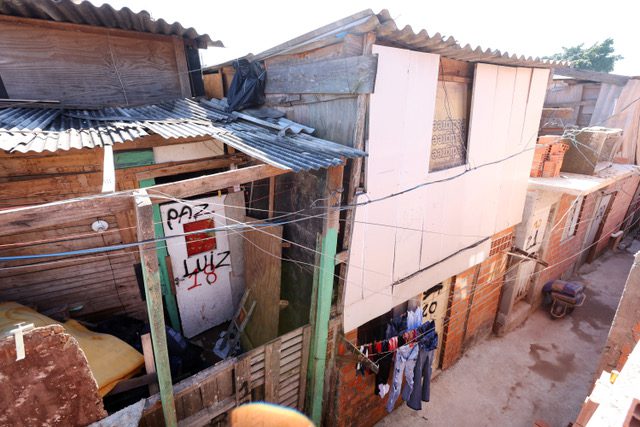

Two years ago, Ana Paula Pimentel Walker, associate professor of Urban and Regional Planning, began knocking on the doors of crudely built shacks in the favelas, or slums, of São Paulo, Brazil, and Bucaramanga, Colombia.

Most of the homes lacked electricity, running water, sanitation, insulation, and heating or cooling systems. In interviews with the residents, she learned about their housing issues and heat-related health concerns.

At each dwelling, Pimentel Walker measured the size of the living space and the roof height. Then she identified the scrap materials ― such as metal, plywood, and cloth ― and local techniques used to build, repair, and expand the structure. She also recorded the ambient temperature inside and outside the house.

It was hot, hazardous fieldwork. But completing this technography of construction practices marked an important first step in Pimentel Walker’s multidisciplinary research project to co-develop passive cooling solutions for self-built housing in low-income communities.

“People living in informal and precarious settlements in sprawling cities or in resource-deprived rural villages of the Global South are adversely affected by increasing extreme weather and temperatures,” Pimentel Walker says. “Indoor heat can exacerbate heat stress and heat-related illnesses. Houses can become heat traps.”

Without timely interventions, more people in self-built housing will experience the ill health effects of extreme heat in coming years, she explains.

A Global Climate Catastrophe

Increasingly, heat and health have garnered global attention.

The World Meteorological Organization reported in November that 2024 was on track to be the warmest year and 2015 to 2024 the warmest decade on record. At COP29 in Azerbaijan, the WMO State of the Climate 2024 Update issued a Red Alert at the “sheer pace of climate change in a single generation.”

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres declared: “Climate catastrophe is hammering health, widening inequalities, harming sustainable development, and rocking the foundations of peace. The vulnerable are hardest hit.”

The COP29 Special Report on Climate Change and Health warned that “climate change poses a fundamental threat to human health and survival” and urged governments, policy-makers, and other sectors to place health at the heart of climate solutions.

Modeling Passive Cooling

Pimentel Walker is putting that mandate into action through her passive cooling research project in Brazil and Colombia.

Funding from the University of Michigan’s “Boost” program, Taubman College’s Pressing Matters grant program, and the U-M Center for Global Health Equity, among others, enabled her to engage global partners and put boots on the ground in São Paulo and Bucaramanga.

Pimentel Walker collaborated with Architecture Professor Lars Junghans, who analyzed temperature data and utilized a thermal comfort model to evaluate 22 different passive cooling intervention candidates. Passive cooling uses design elements and materials to control the temperature and improve the thermal comfort inside a home during hot weather with little or no energy consumption.

These options included coating the walls and roofs of shacks with white reflective paint, covering the roofs with grass or mud, adding insulation and filling gaps, creating a cavity wall, installing a second roof over an existing one, and creating a roof overhang to provide sun and rain protection.

“Our modeling showed that painting a corrugated-metal roof with white reflective paint would lower the temperature inside a São Paulo shack in January by 9 degrees Fahrenheit (5 degrees Celsius) at 3 p.m. in the afternoon,” Pimentel Walker reports.

Other modeling results, particularly the use of multiple cooling methods in a dwelling, were equally promising. Encouraged by these findings, her research team began co-designing implementable interventions to make them affordable, culturally suitable, and appealing.

Pimentel Walker returned to São Paulo and Bucaramanga, where she held daylong workshops with the favela residents, dwellers’ associations, and their partners to gather additional feedback.

“I shared information on why they may face higher mortality rates than other communities due in part to heat exposure and how increasing the thermal comfort inside their homes has positive health outcomes,” she says.

Pimentel Walker passed out surveys and asked residents to choose their favorite passive cooling options. Then they discussed why certain interventions would work better in practice than others.

The project’s initial research phase concluded in June 2024.

“Now our team is seeking funding to implement these passive cooling techniques,” Pimentel Walker says.

Taking the Next Steps

Pimentel Walker shared the results of her team’s passive cooling research with her global partners in Brazil and Colombia as well as with the international community during her appearance at the Group of 20 Social Summit in Rio de Janeiro in November.

Currently, she is working with government officials, nongovernmental organizations, and private industry to implement changes in policies and practices that will improve the housing conditions and reduce the burden of heat stress in informal settlements.

“Eventually, we would like to see international organizations and governments include the point of view of self-built and precarious homes in their heat-adaptation plans and give these settlements top priority since the residents are the most exposed to extreme heat and have fewer resources to combat dangerous heat waves,” Pimentel Walker concludes.

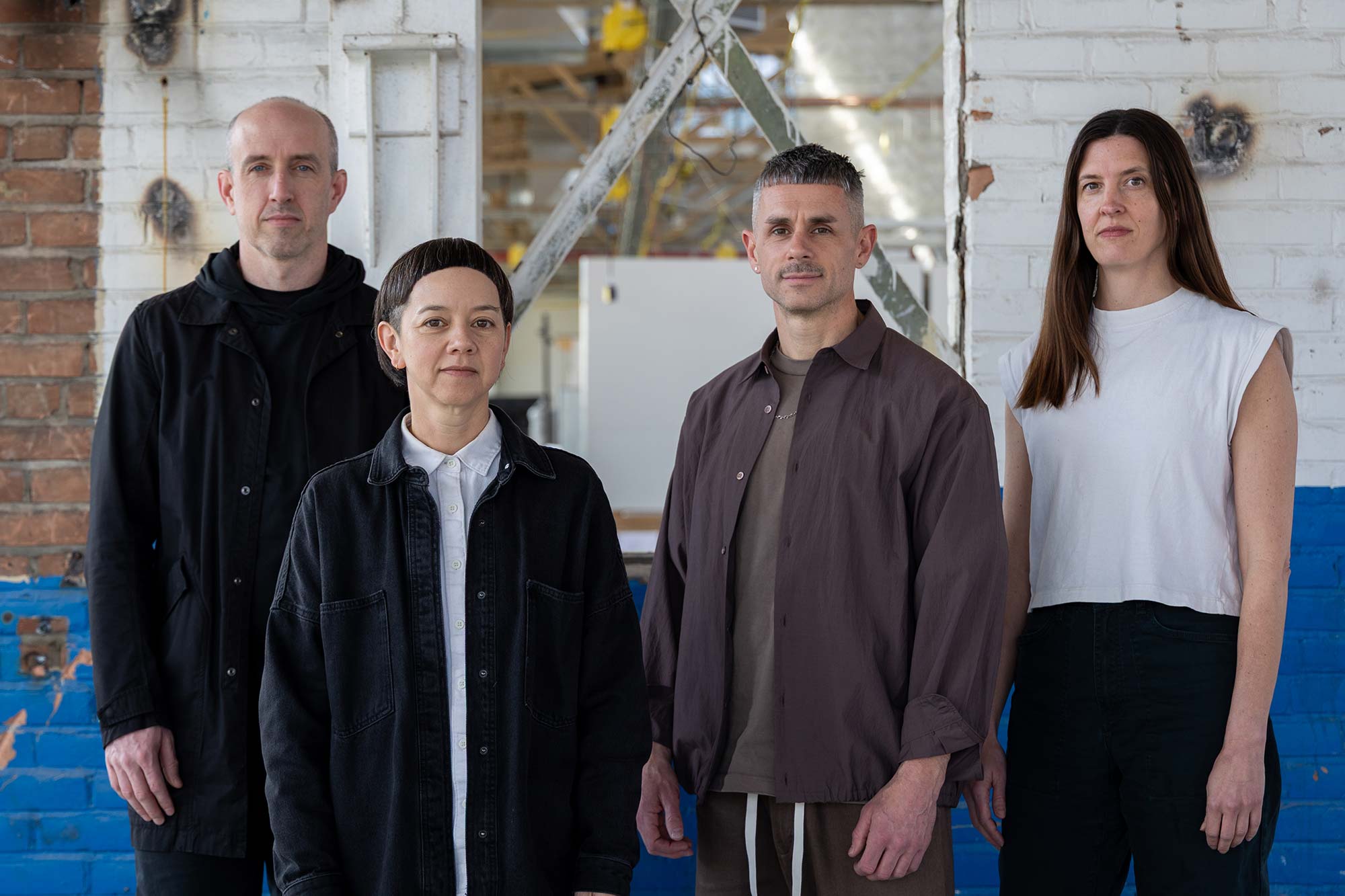

The interdisciplinary research team working on passive cooling can be found at: https://coolcasa.blot.im/people.

— Cladia Capos