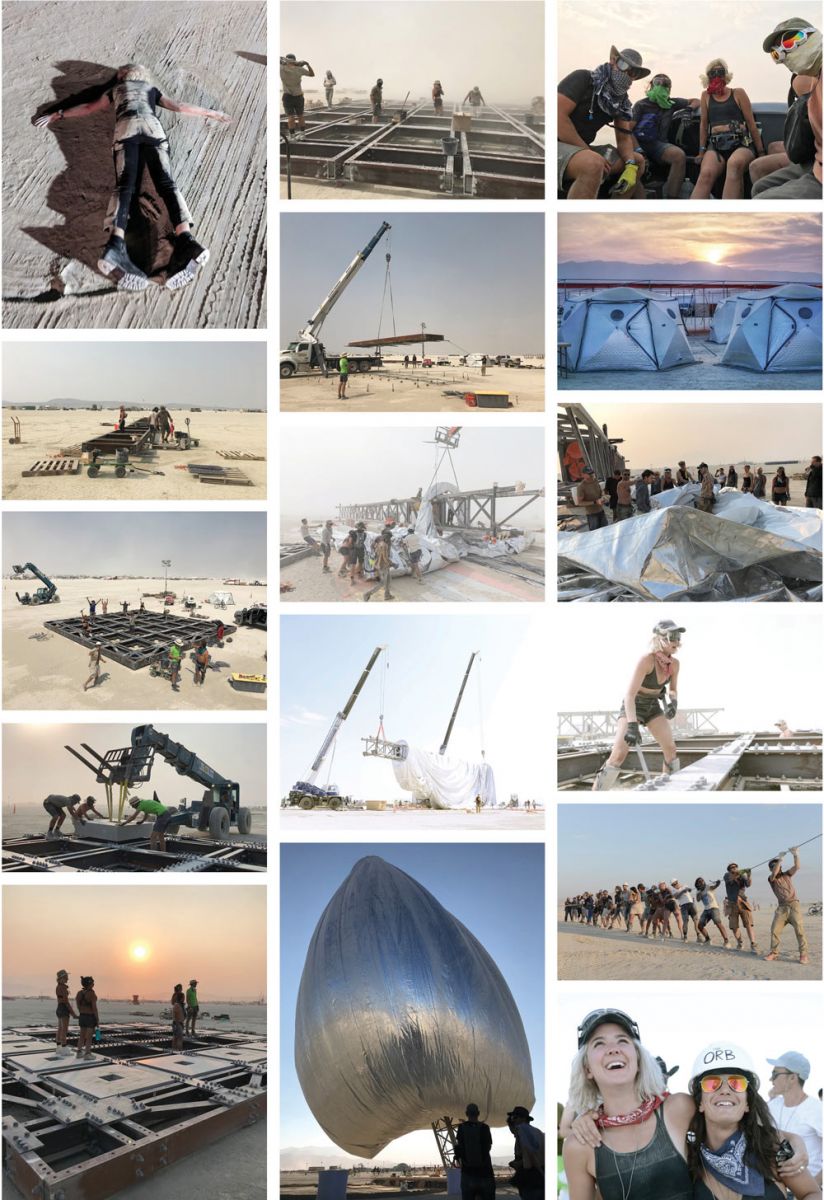

Samantha Okolita, M.Arch '17, Reflects on Building The Orb at Burning Man 2018

By Samantha Okolita, M.Arch ’17

When my colleagues Bjarke Ingels, Jakob Lange, and their friends announced they would build an installation at Burning Man, I eagerly signed on. My experience at Taubman College, and working for my professors at their firms Akoaki and T+E+A+M, sparked my love for fabrication and constructing installations. I was excited to build again.

Samantha Okolita, M.Arch ’17, was part of a 13-person crew that built a large installation at Burning Man 2018, an annual festival in a temporary city erected in the Black Rock Desert of northwest Nevada.

Seven artists, engineers, and architects in all black, like stereotypical New York designers, arrived at the Burning Man gate at 3 a.m. “Where’s the funeral?” asked the gatekeepers. Our initiation, doing a “dust angel,” erased that New York look and began our transformation into burners. I had that coat of dust for the next three weeks.

Our 13-person crew was on a tight schedule to finish The Orb for the first day of the festival. The construction was a four-part process: build the base, zip up the fabric, erect the mast, inflate. The longest, most intense phase was the first; we had to hand-tighten around 5,000 bolts to assemble the 30-ton steel base. It felt like putting a full-scale Lego set together in extreme conditions. We worked 12 to 18 hours each day in the desert heat and nightly sandstorms. We didn’t leave the base; we ate in a small tent while huddled around a dusty table covered in construction drawings and tools.

For an architect, it was interesting watching a city that supports 70,000 people grow from dust in the middle of nowhere. The crew had to establish systems for waste management, shade, water supply, and food storage, as well as fun things like a bar and sound system. There was no free ride; everyone worked together to make it happen.

For the first five days, we had no shower. After that, you could stand under a plastic bag dripping water. The dust in the desert is alkaline and can cause serious irritation to the skin. By day four I had swollen hands and feet, called “playa foot,” that did not go away until several days after returning to NYC.

One night, I woke to someone screaming “Fire!” We ran from our tents to find that the compost toilet had spontaneously combusted. With no fire department to call, we worked together to extinguish the fire. Three hours later, we were back outside building.

After five days, we completed the base and lowered in the concrete weights. Next, we had to zip together eight pieces to form the 83-foot-diameter balloon. When we took it out of the shipping container, I repeatedly swept the balloon to minimize dust. We realized this was a Sisyphean task after the first dust storm covered the fabric in a dune. Zipping eight pieces of fabric together sounds easy, but two tons of fabric in 30-mph dust storms was anything but that. Luckily, the 105-foot steel mast, which arrived almost completely assembled in three pieces, was easier. After the balloon was assembled into two parts on either side of the steel mast, the whole camp crew helped us lift the fabric over the mast so we could zip it together. A dust storm hit during this, and it felt like we were all on a sinking ship that we were desperately trying to keep afloat. We held the fabric up from underneath inside the mast while the fabric and zipper master slowly closed the balloon. That one zipper took almost an entire day.

Finally, we were ready to lift the mast, using the crane from Burning Man’s support services. But a wind storm snapped off the ties that were supposed to hold the balloon to the mast. We quickly tied a rope around the balloon, trying to secure the fabric that was like a sail in the wind. People on the playa saw us struggling to hold on, so many helped hold the rope for almost an hour until we secured it to a truck. As we then tried to resolve a problem with the hinge that connected the mast to the base, the crane operator realized that the crane was too small to fully erect the mast. After lowering the mast and much deliberation, we forged a plan that required two cranes: one would lift the mast and pass it to the other, slightly closer to the base, and then back to the first crane after moving closer.

After several hours, we secured the mast to the base and were in awe of how large this installation was. The next day, a fellow burner in a cherry picker hundreds of feet in the air closed off the final zipper. After some patch work on various punctures, we inflated the balloon. We completed the installation a little late — halfway through the first day of the burn. In the end, I thought this was better because everyone had already arrived and there was so much talk about our build. The inflation felt like a communal event. We inflated at sunset while a DJ played music; a large crowd cheered and danced as we watched it grow together.

The Orb, the second-tallest structure on the playa, was a centerpiece for Burning Man. Over the next week, we watched people interact with The Orb. Art cars set up nearby and projected lights onto the surface while burners danced. During the day, people found refuge from the sun in its long shadow. At night, the installation looked like a weightless silver sphere. One morning an orchestra played underneath as the sun rose over the desert — an emotional experience. The Orb was our gift to the playa, but the Burning Man community brought it to life.

Samantha Okolita, M.Arch ’17, is a designer working on product development in the Design Innovation Studio at WeWork, based in New York. When she’s not erecting massive installations in the desert, she focuses her practice on imagining possible future architectural organizations in response to climate change, automation, and shifting cultural paradigms.