Celebrating Twenty-Five Years as Taubman College

[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”4.16″ global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_row _builder_version=”4.16″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” global_colors_info=”{}”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”4.16″ custom_padding=”|||” global_colors_info=”{}” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”4.16″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat” global_colors_info=”{}”]

As Taubman College celebrates a quarter century since A. Alfred Taubman’s transformational naming gift, we honor the past and embrace a promising future.

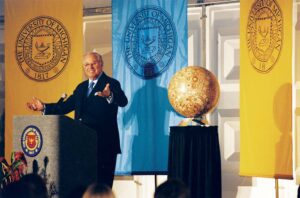

In 1999, when real estate developer and investor A. Alfred Taubman gave $30 million to the University of Michigan College of Architecture and Urban Planning, the donation sent ripples not only through U-M, but across higher education. For one thing, the amount itself was unprecedented — in the words of then-President Lee C. Bollinger, it was “one of the largest gifts in the University’s history and the most generous single gift ever made to a school of architecture in the United States.” But the sum would also transform the school that soon became known as Taubman College in ways its faculty, students, and alumni — present and future — could only begin to imagine.

“I was just learning the landscape of architectural education,” says Dean Jonathan Massey, who at the time was working toward his Ph.D. in architecture at Princeton University. “Even as a graduate student I heard about the naming gift, and it was my first introduction to the University of Michigan. It was such a strong commitment and such a big, game-changing investment — a vote of confidence in what was happening at the school.”

A quarter century later, that vote of confidence has helped Taubman College earn and maintain a place among the country’s top schools of architecture and urban planning. Meanwhile, a generation of architects and urban planners has benefited from the increased opportunities that Al Taubman’s gift made possible.

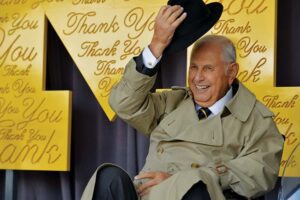

The son of Jewish immigrants from Poland, Al Taubman was born in 1924 in Pontiac, Michigan. He studied architecture at U-M, taking a break to serve in World War II before returning for another year. Al Taubman’s deep affection for U-M remained a constant throughout a long career in real estate development and investing. His eventual donations to his alma mater, including not only to Taubman College but also to Michigan Medicine and the University of Michigan Museum of Art, would total some $160 million.

“I owe the University of Michigan more than I could ever pay back in my lifetime. My experiences here as a young man helped shape every aspect of my life, and this university contributes so much to our state and our nation. I will be forever grateful.”

– A. Alfred Taubman

A self-made billionaire, Al Taubman made his first fortune in shopping malls, designing and building successful retail centers across the country, including Ann Arbor’s own Briarwood Mall and Arborland. He studied Americans’ changing habits, becoming an expert in consumer behavior during the booming post-war decades. And he was just as deliberate — and detail-oriented — when it came to giving his money away.

Associate Professor of Architecture Melissa Harris, then the college’s associate dean for academic affairs, remembers visiting Al Taubman in his Bloomfield Hills office as part of a U-M delegation that was presenting designs for the college’s new A. Alfred Taubman Wing (funded by another, separate gift). Al Taubman, who sat in a swiveling chair surrounded by telephones, offered cogent criticism, including insights into the proper configuration of the building’s entrance.

“He said, ‘You don’t turn to enter a building,’” Harris recalls. “‘The entrance should be perpendicular to your path.’ It seems like a really simple thing, but he knew how to move people around.”

Al Taubman’s naming gift put U-M at the center of a wider conversation about the future of architecture and urban planning education, but it was also the subject of a heated debate on campus. Naming gifts were still a fairly new idea — after the Rackham Graduate School building, built in 1935 with a $6.5 million gift from the eponymous Detroit foundation, Taubman College was only the second school at U-M to be named for a donor.

Al Taubman wanted the endowment’s proceeds to transform the college, so he made his gift without restrictions, knowing that over time the college’s needs would change.

“His vision and understanding about the need for flexibility as time moved has allowed the college to transform over time and into the future,” says Cynthia Radecki, Taubman College’s assistant dean for advancement.

Soon after announcing the gift, Taubman College began expanding its faculty, sometimes branching out in new directions in research and teaching. The first hire was Robert Fishman, who brought the discipline of urban history to Taubman College. Fishman, who retired in 2022, “helped transform the way architecture students think about cities,” Harris says. “Really, he was the perfect first appointment.” The endowment distributions have continued to support many other key faculty through the years.

Meanwhile, the college established the Taubman Scholars program, which provided merit-based scholarships with the aim of attracting top talent from around the world. To date, the program has supported more than 1,800 students, including Ryan Michael, B.A. ’08 (LSA), M.U.P. ’10, for whom a scholarship helped reduce the cost of a master’s degree that launched his career in economic development. Like many other recent graduates, he has spent the past decade contributing to what has been termed Detroit’s renaissance.

“My capstone project at Taubman was directly related to the work that I ended up doing,” notes Michael, who is now a senior executive in the Office of Future Mobility and Electrification at the Michigan Economic Development Corporation. “I know Mr. Taubman’s naming gift has helped a lot of people from different circumstances, people for whom that money let them go much further. So I’m definitely grateful for it.”

The gift has also allowed Taubman College to expand travel opportunities for students, helping to make it a truly international institution.

“A lot of our travel is about seeing the relationship between different cultures and the built environment,” says Chair of Architecture McLain Clutter, who has taken students to megacities like São Paolo, Mumbai, and Mexico City. Such experiences are particularly valuable, he says, for students from the United States, who find themselves “completely outside of their known experience” for what may be the first time.

Anya Sirota, associate dean for academic initiatives and associate professor of architecture, is heading the spring travel program in 2024. She agrees that the shift in perspective catalyzed by travel is vital for a budding architect or urban planner — and that works best when travel is guided by intellectual curiosity, unhampered by individual finances.

“This gift allows us to be incredibly free, and it supports liberal thinking in a way that’s really unprecedented,” says Sirota, who plans to take a studio to France in the spring to study “Zones to Defend,” a series of militant occupations organized to oppose development in the French countryside. “That opportunity for students to share, and to be inspired by, alternate ways of doing things through a global perspective — that’s priceless.”

Al Taubman was not only a donor, but a fundraiser as well. At the time of his death in 2015, at 91, he was serving as vice chair for U-M’s Victors for Michigan campaign, a $5.28 billion fundraising effort to support student scholarships, among other priorities.

“My father never intended for his donation to be the only large gift to Taubman College,” says Bill Taubman, Al’s son and member of the Taubman College Dean’s Advisory Board. “He understood the profound impact donors can have on the college’s future and was passionate about inspiring others to give generously in order to continue moving the college forward, while opening the door for more students to take advantage of the rich educational experience the college offers.”

Student experience is also front-of-mind for donors like Randy Howder, B.S. ’99. “By opening doors to a design education, donors can ensure a future generation will have the critical thinking, creative solutions, and communications skills necessary to create a more equitable, just, and sustainable society through the built environment,” he says. “I hope to open doors to those who would not otherwise have the opportunity to attend a world-class institution like Taubman College and to bring more diverse points of view.”

“Philanthropy will in the future, as it has in the past, make the difference between a good school and a great school,” agrees Daniel Swartz, B.Arch ’71, M.B.A. ’73, noting that his personal aim in donating to Taubman is to “make some yet unknown student’s life a little easier and less stressful.”

That’s certainly something that current students appreciate, especially as the cost of higher education in general continues to rise. Urban and regional planning master’s student Keiaron Randle still has loans from her undergraduate degree in social work at Baylor University. This year, she’s a Taubman Scholar, and last year a scholarship funded by the Detroit-based infrastructure consulting firm AECOM helped the Texas native continue her education without much additional debt — a stroke of good fortune that also lets her make career decisions based on passion and principles, rather than on the need to pay back student loans. Katie Johnson, B.S. Arch ’03, M.Arch/M.B.A. ’10, a member of the Taubman College Dean’s Advisory Board and a former Taubman Scholar, was instrumental in establishing the scholarship.

“AECOM have been amazing — they helped me find an internship over the summer, and I’ve also been to their offices in Detroit to network,” says Randle, who hopes to work in the city after graduation. “But it’s also been great just being able to focus on my studies and work a little bit less to cover expenses. I truly would not have been able to get this degree without it.”

Al Taubman himself was philosophical about philanthropy, realizing that his gifts to U-M and other institutions were valuable beyond the dollar figure. In 2011, he recalled learning about the importance of giving back from his father, who had also built his own business before losing everything during the Great Depression.

Al Taubman himself was philosophical about philanthropy, realizing that his gifts to U-M and other institutions were valuable beyond the dollar figure. In 2011, he recalled learning about the importance of giving back from his father, who had also built his own business before losing everything during the Great Depression.

“When my father went out to raise funds for good causes, he used to say, ‘If I make a donation, I have given once,’” Al Taubman said. “‘If I then solicit monies, I gave twice. And if my contribution has inspired others to support a good cause, I will have given three times.’”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

Portico: Fall 2023

- Patricia Gruits, B.S. Arch ’04, M.Arch ’06, is Doing More with Purpose-Driven Architecture

- Whitney Kraus, B.S. Arch ’05, Bridges the Gap Between Designers and Developers

- Rich von Luhrte, B.Arch ’68, Funds Scholarships to Continue His Legacy of Addressing Climate Change

- Dillon Erb, M.Arch ’14, and Daniel Kobran, M.Arch ’14, Explore the Benefits of Paperspace’s Acquisition by DigitalOcean

- From Michigan to Ghana to Michigan: Architecture as Culture, Collaboration, and Community

- Celebrating Twenty-Five Years as Taubman College

- Help Taubman College Build Tomorrow: Martin Rodriguez Jr.’s Story