Turning Auto Waste into Building Material

With Post Rock, a Taubman College research team led by Associate Professor Meredith Miller is developing an innovative cladding made from automotive plastic scraps.

Imagine the exterior walls of your office building were covered with a plastic waste product recovered from automotive plants — a durable, hybrid material that’s also eco-friendly.

Meredith Miller and a team of fellow Taubman College researchers are in the latter stages of a long-running project to create such a building material. Their innovation, called Post Rock, is part of a sustainability movement that’s helping redefine the very nature of architecture.

“There was this idea that architecture could be really different,” says Miller, an associate professor of architecture and director of the Master of Architecture program. “We could make buildings out of garbage and think that they’re beautiful.”

Miller, the principal investigator, is joined on the research team by Thom Moran, an associate professor of architecture, and Chris Humphrey, a lecturer in architecture. In 2023, the team received a two-year National Science Foundation grant for the Post Rock project.

The team’s plastic-forming process is already patented. Miller wants to commercialize this process by developing a building product made from automotive plastic waste. She says the NSF grant will allow them to examine the largest waste streams from the auto industry and determine which polymer types may be suitable as a building material.

Automotive plastics are a perfect fit partly because they’re regionally available. Plus, Miller says, cars are well regulated so there are numerous safety and health guidelines about what can go into them. And, finally, any high-quality plastics used in vehicles are strong, durable, and impact-resistant — characteristics that would make them an ideal building material.

The application the team is targeting is a building cladding that makes up the outer layer of an exterior wall. But first, it must meet fire safety regulations. Miller is interested in learning “which of the various types of plastics used in cars would work for our process.”

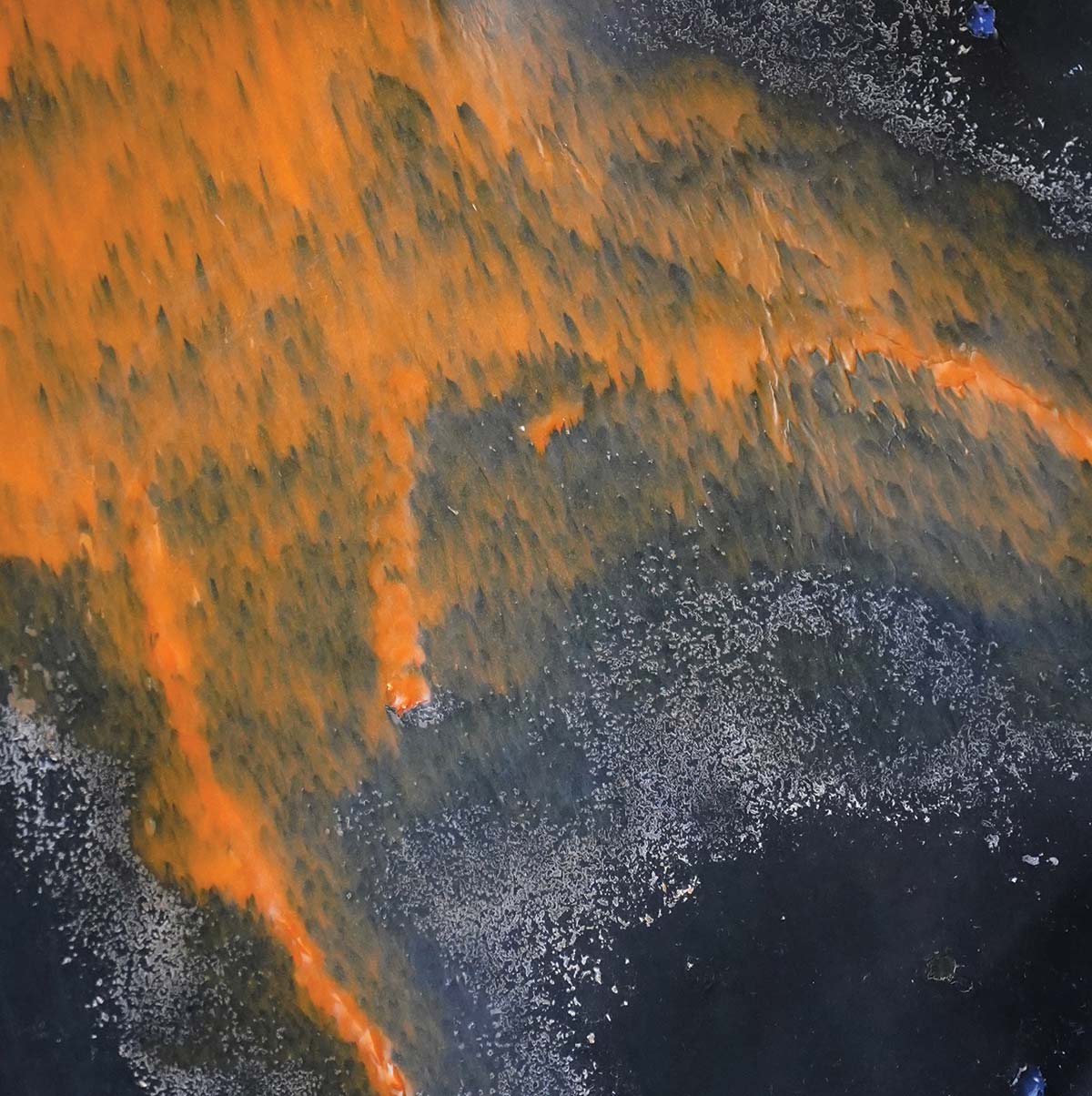

The effort has been 10 years in the making for Miller and Moran. They were initially inspired by a 2014 article in Geological Society of America journal about a new kind of geological specimen in marine environments — “rocks” that are formed when plastic materials like fishing lines and shampoo bottles are fused with sand and seashells.

While these new rocks signaled the growing pollution problem, they also raised the possibility of combining waste plastics with other materials to make them useful. “There’s a kind of beauty to these objects,” she says. She wonders if “we could harness that beauty” to incentivize diverting that waste in the first place by making architectural materials that have a similar aesthetic — a “chunky hybrid” of natural and man-made materials.

The project started in a fabrication lab as a design experiment. But Miller realized that to create something that could be sold to architects around the country and have a significant impact on the waste problem, it needed to be at a much larger scale. Currently, the research team is designing a mockup of a portion of a wall made with this recycled material that will be rigorously tested.

One appealing feature is that Post Rock could have a “regional flavor.” In other words, Michigan Post Rock made from automotive waste could look different from Post Rock made from waste in other areas.

Within the next two years, the team will decide whether the results are promising enough to launch a company and operate as a startup.

Another goal is to quantify and document the environmental impacts across the material’s life cycle and examine the journey the materials took.

While it’s too early to understand the impact of using this alternative material, Miller remains optimistic. “When you account for the whole building impacts of creating a lighter building and sequestering plastic,” it’s a promising technology, she says. “That’s why we remain committed to it.”

The research into Post Rock has given Miller an appreciation of how architecture relies on many other fields.

“We can’t just be laser-focused on our job,” she says. “We have to understand the broader ecosystem behind building construction if we want to improve our building sustainability.”

Ultimately, the research reflects how architecture can be reimagined to better protect the environment.

“Our expectations of what architecture can be can sometimes be limited,” Miller says. “To solve some of the problems of architecture’s disproportionate impact on resources and energy, maybe we have to not only make architecture more efficient but also change our imagination of what architecture can be.”